The Arabic and Islamic worlds are rich in tales of martial prowess, nobility, mercy and diplomacy, inspiring academic Remke Kruk to shine light on powerful female figures and bring them charging in from the margins of history.

“I wonder who this horseman is. By Allah! He appears to be quite daring and brave,” were the words of one of Islamic history’s bravest of generals, Khalid Ibn Al Walid (529-642AD), who was a companion of Prophet Mohammed.

Ibn Al Walid's reaction to this "mysterious warrior" who appears on the battle scene against the Byzantines, is a chapter in history noted down meticulously by the Arab historian Al Waqidi (747-823 AD), in his book The Conquest of Al Sham (greater Syria).

He goes on to write: “In a battle that took place in Beit Lahia near Ajnadin, Khalid [ibn Walid] watched a knight, in black attire, with a big green shawl wrapped around his waist and covering his chest. That knight broke through the Byzantine ranks like an arrow. Khalid and the others followed him and joined battle.”

That black-clad knight disguised as a man was the Muslim Arab woman warrior Khawlah bint Al Azwar. Born in the seventh century in the area that today comprises Syria, Jordan and Lebanon, Khawlah’s beauty, bravery and poetry have stood the test of time and become the stuff of legend.

“The mysterious warrior pounced on the enemy like a mighty hawk on a tiny sparrow in an attack that wreaked havoc in the Byzantine lines,” wrote the historian.

Khawlah was a daughter of one of the chiefs of the Bani Assad tribe, and had fought in many battles, and one of her more famed conquests is this battle as described by the historian, where she rode over to save her brother, Dirrar ibn Al Azwar, a commander in his own right, after he was captured by the Byzantine forces.

Her story is still relevant, with Iraq’s all-women military unit and the Gulf’s first military college for women, based in Abu Dhabi, named after her.

The college opened in 1991, after the first Gulf War, under directives of the Founding Father Sheikh Zayed to prepare young women for careers in the military.

And it has taken off, with a fifth batch of Emirati female recruits joining the Khawla bint Al Azwar military college for girls on September 17 and now wrapping up their first week of training, according to the National and Reserve Service Authority.

While it is mandatory for males to join the army, it is optional for females, who can join between the ages of 18 and 30 and will spend almost a year in training. The daughter and granddaughter of Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, as well as other sheikhas, graduated last month from the college.

“Despite their young age, the daughters of the UAE abandoned their comfort and opted to have the honour of training in military skills. They exhibited patience, determination and perseverance,” said Col Afra Al Falasi, commander of the college, at the graduation ceremony.

One of the first all-girls schools that opened in Dubai was also named after the warrior, when in 1958, the Khawlah bint Al Azwar school opened in Bur Dubai, and in Deira, Al Khansa school for girls opened, named after a prominent 7th-century Arab poetess.

As a timeless example for all powerful women in the region, ISIL must have been bothered by Khawlah bint Al Azwar, and so they destroyed her grave in 2014 in Sermin village, Syria.

But she is one of many Arab and Muslim warriors and fighters whose skills often go unmentioned, such as Al Sayeda Aisha, wife of Prophet Mohammed and Asma bint Abi Baker, daughter of the first Caliphate Abu Bakr and one of the companions of Prophet Mohammed.

Then there was one more warrior, often forgotten. In one of Islam’s greatest battles, at the base of Mount Uhud, an unlikely heroine stood out from the crowd of men.

“Wherever I turned, to the left or the right, I saw her fighting for me,” said Prophet Mohammed, referring to Nasibah bint Ka’b al Maziniyyah, or Umm Umarah as she is better known.

She fought in many battles, attended historic treaties, and even lost a hand in one skirmish. The fact that she was a wife and a mother did not stop her from wielding a sword or tending to the wounded.

"Many women are reported to have participated in the early wars of Islam," says Remke Kruk, emeritus professor of Arabic at the University of Leiden, who has published widely on classic and medieval Arabic culture. In 2014, she published a book titled The Warrior Women of Islam.

Not all took up arms like Khawlah and Umm Umarah, “but encouraged the men with poetry and looked after the wounded”, Prof Kruk says.

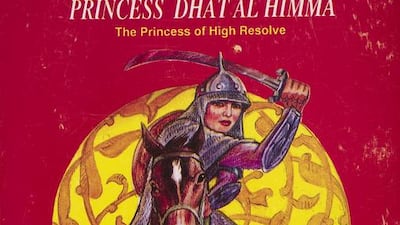

In her book, a reader discovers new heroines from epic tales, such as Princess Dhat Al Himma (the heroine of an epic that already existed in the 12th century) who, like Zenobia, the pre-Islamic warrior queen of the Roman colony of Palmyra, in what is now Syria (ruled from about 267 to 274 AD), led a tomboy youth where she preferred to hunt and wander in the wilderness.

"It is hard to find out how much of the reports about early times is fact and how much is legend. But I am particularly fascinated about the prominent role of warrior women in Arabic popular fiction, such as the Siyar sha`biyya. Obviously, the men who composed these stories knew that their male audiences loved to hear about strong and brave women who were able to defeat men on the battlefield. Is that not surprising?" Prof Kruk says.

One of the professor's favourite Arab princesses is Ghamra bint Utarid, who was mentioned in the epic Sirat al-Amira Dhat al-Himma.

“She was raised as a boy and could defeat all her opponents in combat. She fell in love with her cousin, and was so insulted when he – not knowing that she was a brave warrior – rejected marriage that, disguised as a man, she followed him when he went hunting and attacked him. She defeated him and took away all his armour and clothes, leaving him naked as a baby.

“She never wanted anything to do with him any more, although he later fell deeply in love with her. When she was forcibly married to him she tied him up on her wedding night and fled on horseback to the South Arabian tribe to which her family belonged. There she was received with great joy, and she became a warlord (or rather warlady) in her own right,” she says.

Besides brave warrior women from powerful families and princesses, there were also powerful queens in this part of the world. There was Bilqis, the Queen of Sheba, mentioned in the Bible and the Quran, who is said to have ruled the kingdom of Marib in Yemen around 1,000BC. Her legend is also told in Ethiopia across the Red Sea.

Then there was the Muslim Queen Arwa, who reigned for a long time as Queen of Yemen (1067-1113 AD), first together with her first and then her second husband, and alone after his death. She is also known as as-Sayyida al-Hurra, “the free lady”.

“Up to recent times, practically all the books were written by men, including history books. In the past, women were not supposed to take part in public life, and that is why it is hard to find information about women from the past,” Prof Kruk says.

“We find some stories about women, but these are an exception.”

It is this rarity of stories about women, whether true or pure fiction, that interested Prof Kruk to research and publish her book.

“My book deals with a branch of literature that is almost unknown in the West, namely popular epic, a branch of popular storytelling. It offers not only fascinating narrative material, but also tells us a lot about the interests and preoccupations of the people who listened to those stories,” the author says.

“The particular aspect of these stories that I want to bring into focus in my book is that strong and brave women are very popular in these tales, contrary to what people expect from Arabic stories.”

Perhaps best at capturing the sentiment of the men of the time who fought at one of the battles with the black knight Khawlah, Al Waqidi writes: “After seeing the women fight, the men would return and say to each other, ‘If we do not fight then we are more entitled to sit in the women’s quarter than the women’.”

rghazal@thenational.ae