NEW DELHI // Narendra Modi visited the troubled state of Jammu and Kashmir amid high security on Friday, his first trip to the area since he took over as India’s prime minister six weeks ago.

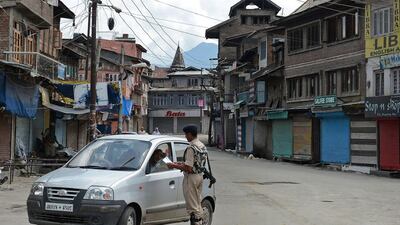

Roads were deserted and many schools and shops were closed in the Kashmir Valley after Muslim groups called a general strike to protest against Mr Modi’s proposed Kashmir policies.

The strike highlighted the mistrust Mr Modi faces in India’s only Muslim-majority state because of his Hindu nationalist background and because of his controversial plans for Kashmir.

These include the resettlement of Hindu Kashmiri Pandits, who were forced out of the state by rising militancy in the early 1990s, in specially created enclaves, and repealing Article 370 of the Indian constitution, which accords an enhanced autonomy to Jammu and Kashmir.

According to this article, which was part of the Indian constitution adopted in 1950, the federal government needs the state’s permission to apply any laws not related to defence, foreign affairs, finance and communications.

Crucially, the federal government cannot unilaterally declare a state of emergency in Jammu and Kashmir except during war or an incident of external aggression.

Article 370, initially intended to be a “temporary provision”, was designed to subdue the various secessionist movements in the state. Other movements in Kashmir aim for it to become part of Pakistan.

India and Pakistan have been in conflict over Kashmir ever since the two countries became independent in 1947, fighting three major wars and skirmishing constantly over the Line of Control that operates as a de facto border.

Ahead of Mr Modi’s visit, Pakistan made sure to re-emphasise its position on Kashmir.

“We do not accept the so-called accession of the state of Jammu and Kashmir to India,” Tasnim Aslam, a spokeswoman for Pakistan’s foreign office. “Kashmir is not an integral part of India. Our position is that Jammu and Kashmir is a disputed territory.”

Since his election, Mr Modi has offered no definitive statements on resolving the Kashmir issue.

Mirwaiz Umar Farooq, the chairman of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, a front of 26 groups seeking self-determination for Kashmir, said on Thursday that “a full-fledged peace process” was required.

Referring to the peace process initiated by former prime minister Atal Behari Vajpayee, a member of Mr Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) who held the post from 1998 to 2004, Mr Farooq said: “The Modi government should follow the path of …Vajpayee, who once declared it his dream and wish to resolve the Kashmir issue and proposed a solution under the ambit of insaaniyat [humanity].”

But “we are yet to see any sign of a clear commitment” to such a process, Mr Farooq said.

However, during his visit on Friday, Mr Modi promised “the people of Jammu and Kashmir that the journey started by Atal Bihari Vajpayee in the state will be taken to its logical conclusion”.

Srinath Raghavan, a senior fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, a New Delhi-based think tank, said Mr Modi has avoided too strident a tone on Pakistan.

“He has said that trust has to be rebuilt with Pakistan, which is the same line that the previous government took,” Mr Raghavan said.

Mr Modi chose to focus more on development than politics during his visit. “My objective is to win the hearts of the people of Jammu and Kashmir through development,” he said.

He inaugurated a 25-kilometre railway line that runs up to the famous Vaishno Devi temple in the Trikuta Mountains, a point of pilgrimage for Hindus. He also launched a hydroelectric plant in the border town of Uri and chaired a security review meeting at an army base in Srinagar, the state capital.

More than 2,000 troops secured the Srinagar-Uri highway to guard Mr Modi’s entourage during its journey. The prime minister himself travelled by air.

Bashir-ud-din, the leader of several Muslim forums that called for the general strike, said Kashmiri Pandits were welcome to return and settle in their ancestral properties, but questioned the plan to form three enclaves for them out of land held by other Kashmiris.

“The move to create separate settlements for them will have serious consequences,” he said.

The chief minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Omar Abdullah, whose party is a rival of the BJP, also argued against the concept.

“The idea is not to put Pandits into ghettos,” Mr Abdullah said on Thursday. “The idea is to get them to assimilate back into the community they left at one point of time.”

Two days earlier, Mr Abdullah spoke out against revoking Article 370, arguing that Jammu and Kashmir’s delicate situation required special autonomy. Greater federal control could strengthen calls for secession, he said.

“I have repeatedly and vehemently highlighted that Jammu and Kashmir cannot be equated with other states of India,” he said.

“We have withstood all challenges in the past and will do it again in the future.”

ssubramanian@thenational.ae