ISLAMABAD // In October, two commodity shortages hit Pakistanis with a vengeance: sugar and hashish.

Both shortages were artificial, manipulated by networks of manufacturers and wholesalers who hoarded thousands of tonnes of stock to send prices and profits soaring.

By November, prices of both commodities had doubled: sugar hit 125 rupees (Dh5.37) a kilo at those shops that were still catering to Pakistanis' sweet tooth.

But that figure paled in comparison to the 50,000 rupees (Dh2,147) a kilo that so-called "A-grade" export-quality hashish reached in the wholesale drugs market of Bara, a smugglers market near Peshawar, according to Fata Research Centre, an Islamabad-based think tank.

After a political furore, authorities dragged the price of sugar back down to 72 rupees per kilo, 10 rupees more than before the onset of shortages.

The price of hashish has stayed put, however.

"The big shots wanted us to reduce our sugar consumption, so we have," said Tasawar Shah, a house painter and resident of Nurpur Shahan.

"Now it looks like we'll have to give up 'medicine' as well," he quipped to a group of friends gathered in his uncle's sitting room.

Medicine is one of several nicknames Pakistanis have given to charas, or hashish.

"It's embarrassing. It has always been custom to offer medicine to our guests. Now it has become so expensive that we have to excuse ourselves by saying we have given it up," Mr Shah said.

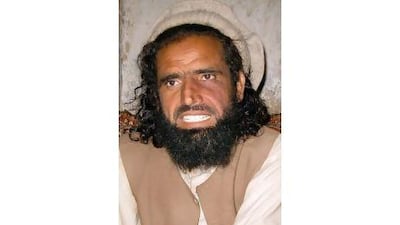

Mangal Bagh Afridi, the commander of the Lashkar-i-Islami, a Pakistani Taliban faction based in the Khyber tribal agency, is a major reason the hashish trade has become a sellers' market.

Khyber agency, home to the Khyber Pass linking the subcontinent with Afghanistan, is the headquarters of a massive drugs trade that sprung up in the 1980s.

Back then, proceeds from huge shipments of heroin and hashish filled the pockets of kingpins such as the late Ayub Khan Afridi, who was a member of the federal parliament in the late 1980s.

Ayub Khan operated with impunity because a significant portion of the proceeds went towards buying weapons for the mujaheddin, fighting Soviet forces in Afghanistan.

Pakistan's Inter Services Intelligence and the US Central Intelligence Agency were complicit in the illicit trade, according to media reports.

That lesson has been well learnt by Mangal Bagh Afridi, a former lorry driver's assistant, who emerged from nowhere in 2006 at the head of a militant faction that seized control of Khyber agency, and by 2009 threatened to take Peshawar.

He was beaten back by a military counter-offensive this year and has retreated to the remote Tirah Valley, where the cultivation of bhang, a subcontinent variety of cannabis, is widespread.

While there are no official statistics on cannabis cultivation, production or consumption in Pakistan, hashish is believed to be the most widely consumed intoxicant in the country.

From the Tirah Valley, Mangal Bagh holds sway over the hashish trade, according to analysts specialising in the murky affairs of Pakistan's seven militant-infested tribal regions, known officially as the Fata.

"Mangal Bagh has transformed hashish into a regular commodity business," said Mansur Khan Mahsud, the director of the Fata Research Centre, an Islamabad-based think-tank.

His research has shown that the militant commander controls the Bara smugglers' market, extorting 3,000 to 5,000 rupees per month from traders, practically all of whom are doubly susceptible because they are migrant Afridi tribesmen from Tirah.

Cynically, the Lashkar-i-Islami describes the payments as zakat, an Islamic tax on disposable wealth.

Mangal Bagh has leveraged that control to massively increase the profitability of the hashish trade, Mr Mahsud said.

Notable among the "reforms" he has introduced to the trade are restricting supplies of A-grade hashish, to establish it as a premium product and the inferior B-grade as standard.

The tola, a unit of weight equivalent to slightly more than 11 grams (usually used to weigh gold), has been reduced to eight or nine grams.

He has also periodically stopped supplies to Bara, creating artificial shortages.

Mangal Bagh ordered a moratorium on hashish sales in October to force up prices and enable him to build up a drug inventory estimated to be worth between 50 million and 150 million rupees, the analysts said.

His intervention has pushed the price from 80 rupees per 11-gram tola of A-grade hashish in 2007, to 650 rupees per nine-gram tola of B-grade hashish at present.

The Anti-Narcotics Force, a military-led law enforcement agency, first noticed Mangal Bagh's impact on the hashish trade in June 2007.

It found that the national price of hashish leapt by an average of 52.8 per cent since June 2006.

"In effect, he has pushed up the price of hashish 10-fold in the last three to four years," Mr Mahsud said.

Mangal Bagh's use of stockpiling as a price-control tool mimics the Afghan Taliban, which stockpiled opium after bumper opium crops in 2008 and 2009 to protect prices, according to the United Nations.

The UN reported that the Taliban has used the shortages of heroin to increase demand and the prices of hashish.