Lebanon might be known for its elegant boutiques, beaches and nightlife but it also a country struggling with an unsolved trash crisis, on the brink of financial collapse and where corruption and mismanagement have driven thousands onto the streets in months of protests.

Tens of thousands have been protesting since October 17 calling for a radical change in governance saying they are tired of political and economic stagnation.

"Everyone should have a fair chance as a Lebanese," Talal Jurdi, 51, told The National from Beirut's Downtown district, where the pristine walls have become canvasses for graffiti artists issuing the movement's demands. "If you succeed in an exam, for example, it must be because you are smart not because you have political connections."

Standing a few feet from a graffiti of a pig with dollar-sign eyes, he worried his school-age son will have to emigrate to find a job.

“We have the best schools and we hold positions of responsibility worldwide, but in your own country they laugh at us.”

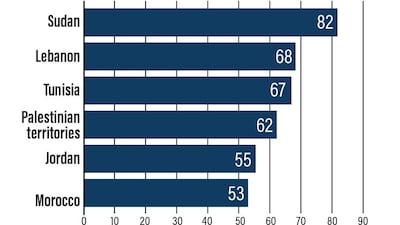

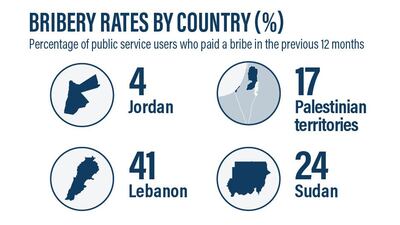

A survey released by Transparency International on Wednesday found connections in Lebanon are not only a key to success but crucial just to survive. In a survey of 1,000 people in the country of around 4.5 million, over half had to rely on political connections – known as wasta – to access public services over the past year while four in 10 or 40 per cent said they paid a bribe.

Lebanon ranked first in the study of six Middle Eastern states when it came to bribery rates. In conflict-ridden Sudan, 24 per cent of respondents (slightly over two in 10 people) paid a bribe in the past year while in Jordan the same metric was just 4 per cent.

The comparison was even more stark when it came to judicial corruption, with 65 per cent of Lebanese respondents said they paid a bribe compared to a flat zero per cent in the case of Jordan.

Corruption and clientelism within ministries are also rife.

On Wednesday a Lebanese prosecutor issued an arrest warrant for the head of traffic management authority, Hoda Salloum, on allegations of bribery, forgery, illicit enrichment and violation of job obligations.

A civil-society initiative that crowd-sourced these instances between 2014 and 2016 found the majority of them (31 per cent) to have taken place within the Interior Ministry, followed by the Finance Ministry (19 per cent).

A ministry employee who spoke to The National on condition of anonymity said "jobs were created expressly for people with political connections" and spoke of widespread harassment and demands for favours of a sexual nature.

A manager who opened a company providing eco-friendly solutions for businesses admitted to having to pay regular bribes to public officers tasked with issuing his permits despite saying he followed the law.

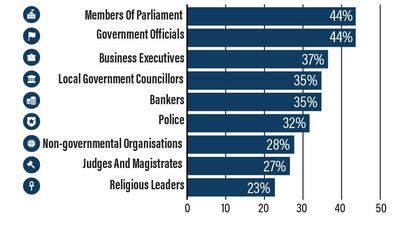

Anti-establishment protesters see the sectarian power-sharing system as responsible for creating a dysfunctional state and causing the looming economic collapse. According to a 2016 study, 18 out of the top 20 banks have major shareholders linked to political elites and 43 per cent of assets in the sector to be under political control.

This phenomenon – described as “crony capital” within the banking sector – in turn impacted the quality of banks’ loans and their exposure to public debt.

Ratings agencies have downgraded several major Lebanese banks assets to junk territory in the past year, expressing concern about the quality of their holdings.

As well as contributing to the dire economic situation, there are real worries about what might happen to funds if exploration finds oil or gas off the Lebanese coast.

Lebanon is in the process of preparing for its first offshore oil and gas exploration but there is uncertainty over transparency and rule of law.

The Lebanese Oil and Gas Initiative (LOGI), an NGO promoting the transparent management of Lebanon's oil and gas resources, has been putting pressure on the Lebanese Petroleum Administration (LPA) to release the names of the local contractors hired by the Total-Eni-Novatek consortium who won the bid.

Diana Kaissy, LOGI's Executive Director, said, “in some cases the names of the companies or of their owners have not been disclosed.” The organisation is calling for the approval of a draft decree for the creation of a Petroleum Registry to guarantee transparency on the ownership.

"We must first reform the system and then we can benefit from oil and gas exploration," Ms Kaissy told The National.

Without reform, activists and monitoring groups say it is likely politicians will use a potential discovery found in January’s exploration tests to attract investments and generate revenues through businesses controlled by their families or sectarian affiliates.

While Lebanon's economy is beyond easy solutions, politicians circulated the idea that the petroleum sector can rescue Lebanon’s economy if explorations proceed fast and without impediments. But expert rebuffed these claims.

“It will take at least 9 or 10 years to have the first revenues” and, even in this best-case scenario, they will not contribute more than 2 per cent of the GDP.

That’s also assuming that any hydrocarbons are actually found and in commercially viable quantities to extract.

If oil and gas is found when the consortium starts drilling early next year, it will benefit the Lebanese economy provided its revenues are managed correctly. But, Ms Kaissy warned, “this sector is not supposed to save us.”