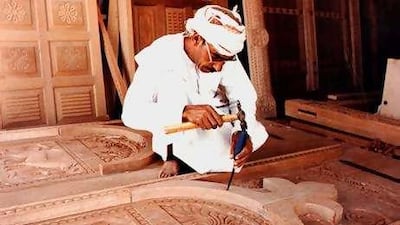

NIZWA, OMAN // Khalaf bin Hamdoon, a 78-year-old Omani master carpenter, was putting the finishing touch on a magnificent carved door ordered by a wealthy Abu Dhabi businessman. The solid teak door and intricately designed frame are hand-made and took Mr Hamdoon two months to make in his workshop at Nizwa, 300km from Muscat.

Such painstaking work costs 12,000 rials (Dh114,000) for both the door and frame. Handcarved Omani woodcraft such as doors, windows, frames and furniture made from imported teak and mahogany timber is a niche market for wealthy patrons. But the future of the lucrative trade is threatened because young Omani men have little interest in the business. They prefer work in the cities to the woodcraft culture.

Government officials say that wood carvers such as Mr Hamdoon are a dying breed and the craft may not survive the next two decades. "Their number is dwindling every decade because they are not replaced when they die," said Saif al Nabhani, an official at the ministry of national heritage. Now, there are just nine left in Oman who use centuries-old hand tools to carve woods in the famed Omani style. In 1993, those craftsmen numbered 16.

Skilled wood carvers enjoyed celebrity status, winning the favours of the sultans of Oman and wealthy tribal leaders, according to another master carpenter, 71-year-old Fadhil bin Khamis. "Wood carvers were famous people and used to be invited to the royal courts. Their work was also commissioned for the sultans' palaces and the residences of rich merchants. Now, there are just a few of us overloaded with orders that we struggle to complete," Mr Khamis said.

Mr Khamis still uses the same workshop that his great-grandfather started in 1889 in the northwest Omani town of Rostaq. But his three sons have moved to larger towns to carve out corporate careers rather than wood. The younger generation say wood carving is old-fashioned, cumbersome and time-consuming. It takes a long time to produce a door or frame. Unless a wood carver is commissioned by wealthy people or government establishments, they sit in their workshops doing nothing.

"Sadly, the romance of being the master wood carver has no place in modern times," said Burhan bin Khamis, the 41-year-old son of the Rostaq wood carver. "Most of these magnificent works are part of history now. You see them in forts, government buildings and the houses of a few rich people. Ordinary people can't afford these works of art any more." sshaibany@thenational.ae