Every Friday, trucks brought the bodies of soldiers from the front lines to the police station in the southern Iraqi town of Samawa.

Thousands of parents would rush to see if their sons were among the dead.

Many, remembers a doctor who served in the town during the brutal Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s, would emerge jubilant and laughing.

“They were so glad that they did not identify their sons among the dead,” she said from northern Iraq where she now lives.

But by the end of years of brutal war – fought with guns, bombs and poisonous gas in trenches, sometimes at close range – almost everyone was affected in Iraq.

“Eventually, almost every single household in Iraq had lost a member in the war,” the doctor said.

Forty years ago, on September 22, 1980, the Iraqi army thrust into the south western Iranian province of Khuzestan, after skirmishes between the two sides and Iraqi complaints of what Baghdad viewed as Iranian incursions into disputed border regions.

It became one of the most devastating conflicts between two nations since the Second World War.

Five months before the guns started firing, Saddam executed Ayatollah Mohammad Baqir Al Sadr after the prominent Iraqi theologian expressed support for the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. The fall of the shah and the rise of a Shiite religious theocracy next door was seen by Saddam as the main threat to his mostly Sunni rule.

In the process, a generation was traumatised on both sides and up to a million people were killed. It wasn't just the soldiers who died. The two countries used ballistic missiles to hammer civilian targets in what became known as the “war of the cities.”

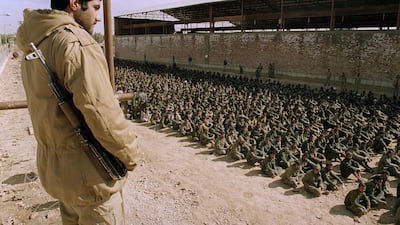

Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini sent boy soldiers, amped up on religious fervour clutching plastic keys to paradise in “human waves" towards Iraqi front lines, saying that they were going to liberate Jerusalem.

Saddam employed chemical weapons. Some were used to neutralise Iranian numerical superiority but well away from the fighting, his air force killed 5,000 when it also gassed Halabja, the Kurdish city in northern Iraq.

Journalists taken by the Iraqi military to the front lines would recall not being able to see the colour of the sky for miles because it was lit by artillery fire, and would describe scenes reminiscent of trench warfare in the First World War.

The Iran-Iraq war mostly transformed by its second and third year, from Iraqi advancements to retreats, and to Iran making inroads into Iraq. It ended in a stalemate, and a ceasefire, in August 1988.

As the tide turned, Saddam portrayed the war as a defence of the motherland, pitting Arabs against Persian invaders and Iraq as the eastern flank of the Arab world. But on the barren borderlands, the mostly Shiite rank and file continued to fight fiercely against their Iranian coreligionists.

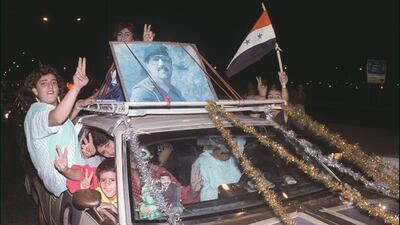

Patriotic songs glorifying the homeland dominated the airwaves, somewhat tempering Saddam’s personality cult.

Iraqi painter and sculptor Ismail Fattah was commissioned to design the Martyr Monument in Baghdad, a rare public venue free from Saddam’s photos since it opened in 1983.

The monument comprises two huge blue hearts almost facing each other. Etched underneath on concrete walls are names of the thousands of Iraqi soldiers killed in the war.

In southern Iraq, for years later Saddam’s posters remained conspicuously absent from the Al Faw peninsula, although the Iraqi Republican Guards regained the territory in April 1988 after Iran occupied it for two years.

"Slow down and be gentle when walking in Al Faw. It is the land where the blood of 52,846 Iraqis was spilt," a placard at the entrance to the peninsula reads.

While a chapter in the history of two nations written in carnage, it is a conflict that has and continues to shape the Middle East today. For many, it is not history at all.

During the conflict, Iran’s current president, Hassan Rouhani, was one of the main war planners. Sitting Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei was president.

Diplomats recount that in numerous meetings behind closed doors with their Iranian counterparts in recent years, Iranian officials keep bringing up the war.

The pain of the staggering loss of Iranian lives, often due to the poor training, equipment and tactics of the military, has led Tehran to pursue an unconventional deterrence.

Aware it is unable to dominate with regular armies against its neighbour – or more recently against superpowers like America – Iran has cultivated and created powerful proxy forces, and became skilled in sabotage, subterfuge and subtlety. It engages political meddling, cultural outreach and, for when all else fails, Tehran has a domestic drone and ballistic missile programme. Both of these have been provided to their proxies from Yemen to Lebanon to be used against Iran's foes.

Then there is its nuclear programme. While Tehran has insisted for years that it is for peaceful means, the enrichment of uranium has led to years of sanctions, weapons inspections and political isolation.

But even as Iran clashes on the world stage with America, Tehran's eyes have never left Baghdad.

Iranian officials have justified their networks of overlapping and interlaced Shiite militia clients in Iraq by saying that they cannot allow Iraq to ever again be a launch pad for what they see as Sunni aggression.

Many secular Shiite Iraqi officers who fought in the war later defected to Iran and Europe. But many returned to Iraq when the US-led invasion toppled Saddam in 2003.

They wanted to be on the vanguard of a nation they wanted to be free of the destructive Baathist ideology of Saddam as well as the Khomeinist militancy.

Among those officers was Tawfiq Al Yassiri, the grandson of one of the leaders of the 1920 uprising against British rule.

Al Yassiri fought, unsuccessfully in the end, to seperate the army from politics in the post-Saddam era and founded a movement comprised mainly of war veterans for that purpose.

Before he died of the coronavirus in June this year, Al Yassiri said that the Iran-Iraq war taught him wisdom and respect for human rights.

“Saddam, driven by sectarian hatred, wanted to destroy as much of Iran as he could,” Al Yassiri said. “He also destroyed Iraq."

But men like Al Yassiri seeking to build a new Iraq were constantly undermined by Shiite militia warlords and their political associates who have left the country a hyper-partisan quagmire of poor governance where powerful gunmen feel they can act with impunity.