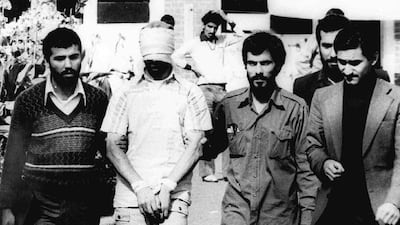

ANKARA // Three decades after hardline students occupied the US embassy and took diplomats hostage for 444 days, many of the now middle-aged revolutionaries are among the most vocal critics of Iran’s conservative establishment.

The role of the students is back in the spotlight following the appointment of a new UN ambassador who may have participated on the fringes of the siege, the event that led Washington to sever ties with Tehran shortly after the 1979 Islamic revolution.

The US State Department, which has yet to approve a visa for Hamid Abutalebi, said it had raised “serious concerns” with Iran about his nomination for the post. On Thursday, 29 Republican senators wrote to the US president, Barack Obama, urging him to deny Mr Abutalebi.

But Iran hopes the case can be resolved, while Mr Abutalebi has played down his role in the hostage crisis, suggesting he was just a translator.

“He is one of Iran’s most prominent and senior diplomats. We hope there will be an agreement [to his appointment] in the normal way,” Iran’s deputy foreign minister, Hossein Amir Abdollahian, said.

Mr Abutalebi has held postings in Europe and was appointed deputy director of political affairs in the office of the president, Hassan Rouhani, in September. Friends say that like many of his fellow former student activists, he is now pro-reform.

People who know Mr Abutalebi said he was part of the student group that occupied the embassy, although not among the core activists inside the embassy who captured and held the hostages.

Lawyers for the former captive embassy workers have said the former hostages are angry about the nomination of Mr Abutalibi, a man they say was involved in the crisis, and want him barred from New York.

But some analysts and officials argue that with the passage of time, most of the leaders of the 300 or so radicals whose action galvanised world attention have become outspoken advocates of the need to reform Iran’s Islamic political system.

“They are simply middle-aged Iranians who now even advocate close ties with the West,” said a senior Iranian official.

Some paid for their change of opinion with arrest, seen by security hawks as a threat. Some won prominence under the former reformist president Mohammad Khatami, but moved to the political margins under his hardline successor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad.

As students, almost all of the hostage takers were active in the revolution that overthrew Iran’s US-backed shah. But years later, the ranks of the hostage takers also gave birth to a movement for reform of Iran’s Islamic system, analysts said.

Evolution, not revolution

Like many ordinary Iranians, the former students opposed powerful hardliners who considered any talks about normalising ties with “the Great Satan” anathema.

Many Iranians are not anti-American. Thanks to the internet and illegal satellite television, US popular culture is influential among young Iranians.

However, the pro-reformist ex-hostage takers are limited in their ambitions. They are committed to the Islamic Revolution, but want to reform the establishment within that framework.

“They are not pro-Western, though they support engagement with the West. They do not want revolution but want an evolution,” said the analyst Hamid Sedghi.

Among the hostage takers were Abbas Abdi, an adviser to Mr Khatami, who in 1998 met former hostage Barry Rosen in Paris.

Mr Abdi made no apology and said the past could not be altered. Instead “we must focus on building a better future”, he said.

In 2002, Mr Abdi was arrested for having carried out a poll in collaboration with the US firm Gallup which showed that three quarters of Tehran’s citizens favoured a thaw with Washington.

The reform leader Saeed Hajjarian survived an assassination attempt in 2000 but was gravely injured and has not recovered. Mr Khatami’s younger brother Mohammad Reza and his deputy foreign minister Mohsen Aminzadeh were also among the hostage takers.

While some of the group have disappeared from politics, others are still ardent defenders of Iran’s strict religious rule and defiance of the international community.

“Some of them still believe the embassy takeover helped strengthen anti-American fervour in Iran,” said analyst Hamid Farahvashian. “But most of them believe in reforms.”

Falling off course

Mr Ahmadinejad’s disputed re-election in 2009 ended an era in which former hostage-takers held key positions in government and parliament.

Disagreements between former hostage takers and hardliners came to the fore after the 2009 vote, which the opposition said was rigged and ignited eight months of violent street unrest.

In a comment widely taken as a reference to the turmoil, former hostage taker Masumeh Ebtekar wrote on her blog Persian Paradox: “Those who were all devotees and trustees of the Islamic Revolution ... felt that the Islamic Republic is facing a serious challenge to its basic principles and values.”

Ms Ebterkar, who was Iran’s vice-president under Mr Khatami, a post she resumed under Mr Rouhani, was the public face of the siege, serving as a spokeswoman for the hostage-takers.

Aides to reformist candidates were jailed in the post-election unrest, including former hostage takers Mohsen Mirdamadi and Mr Aminzadeh, on charges including “acting against national security” and “propaganda against the system”.

Mr Mirdamadi was sentenced to six years in prison and a 10-year ban on political and media activities. He was temporarily released in December 2013. Mr Aminzadeh, sentenced to six years in jail in 2010, was freed in 2013 after 10 months in hospital.

“The slogans that carried us forward as revolutionary students in 1980 might no longer hold all the answers to the problems of today,” wrote Ms Ebtekar.

Ebrahim Asgharzadeh, who was also a spokesman for the hostage takers, has also hinted he is no longer a hardliner.

“Now I am more experienced and more realistic,” Mr Asgharzadeh, a former member of Tehran’s city council, was quoted as saying by Iranian media. “I no longer take radical actions and I believe gradual reforms last longer than radical changes.”

* Reuters