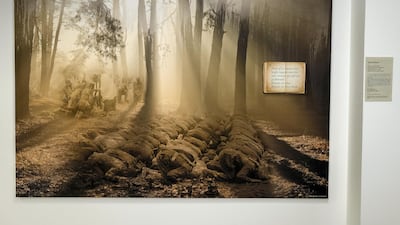

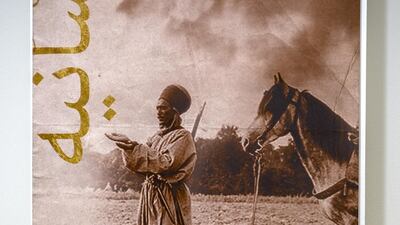

The scrawny Arabic handwriting of a young, desperate soldier spells out his despair.

“We live in caves like hedgehogs. Allah has forsaken this place,” reads one line.

This is not a wail from the desert of the Sahara or from the tunnels of Aleppo, but a carefully preserved letter from the trenches of Europe during the First World War.

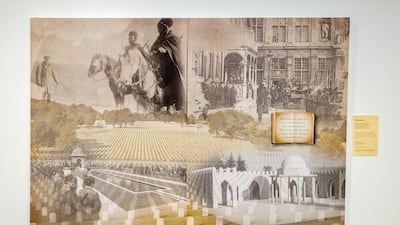

The handwritten letter is just a small part of a London exhibition reminding visitors of the millions of Muslims who fought and died in the Great War.

Now, as Europe approaches the 100th anniversary of the armistice agreement that silenced the guns of the conflict, efforts are under way to shed light on the involvement of troops from the Middle East and Asia.

The ground floor of a vacant office building in Hammersmith on a Sunday is perhaps not the sort of place one might expect to find this battle of narratives, but Luc Ferrier, a former aviation executive from Belgium, is doing what he can to spread awareness of the Muslim contribution to the First World War.

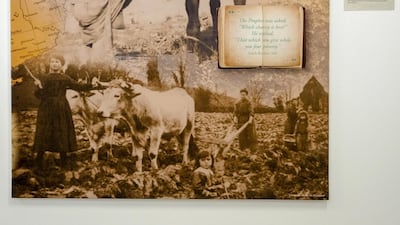

Mr Ferrier was prompted to delve into the sacrifices made by the many Muslims who fought during the conflict after reading some of his grandfather’s notes from the trenches.

Much of the exhibition is based on the contents of a book put together by Mr Ferrier titled The Unknown Fallen.

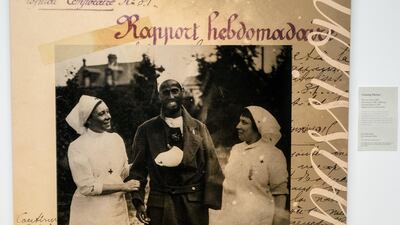

It is a coffee table volume that uses portraits and translations of letters to depict the realities for the Muslims who found themselves in the trenches - a powerful visual reminder that this chapter of history was not solely European.

“I’m not a writer, I didn’t want to write a book that would sit on the shelves of another academic,” he says.

It also touches on the realities of staying true to one’s faith in war.

“They didn’t just have a physical fight but one for identity,” Mr Ferrier says. “How do I stay a good Muslim in the trenches?”

__________

Read more:

How the First World War shaped the borders of the Middle East

Sykes-Picot is history ... it should stay that way

__________

The exhibition has anecdotes of Indian soldiers frustrating their officers by sharing rations with prisoners, something many deemed an obligation of their faith. Other letters document soldiers' concern over whether their rations were halal or not.

The number of Muslims who fought in the First World War is vast and though the exact figure is contested, Mr Ferrier says 4.5 million is historically defendable.

“That includes more than a million from Russia, 400,0000 from North Africa,” he says.

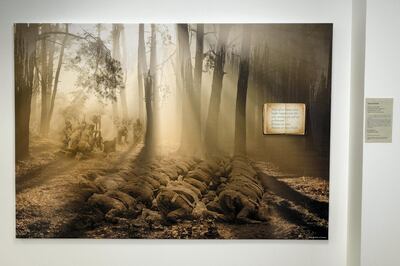

The exhibition brings to light a rarely acknowledged aspect of the Great War, one in which soldiers of all creeds and religions fought side by side, fighting and sacrificing for one another, regardless of belief.

“There is almost no evidence of racism or intolerance. They couldn’t care less about that,” Mr Ferrier says.

He stresses the exhibition is not about glamorising war, nor is it about putting anyone on trial. “It’s a wonderful story about empathy and about brotherhood and friendship.”

The organisation Mr Ferrier now runs – The Forgotten Heroes Foundation – has had success in getting their story to the most unlikely of places.

Hayyan Bhaba, Mr Ferrier’s partner in the venture, recalls pitching their work to Ivan Humble, a former senior member of the English Defence League.

“He was shocked and amazed,” Mr Bhaba says. They now consider him a supporter of the foundation’s work.

One wall of the exhibition is plastered with letters of gratitude and commendation from government and military officials.

A wider effort to further recognise the contributions of Muslims and other minorities who served during both world wars is under way.

Last week British Prime Minister Theresa May vowed to wear a Khadi poppy, in remembrance of the contribution of Indians to the war effort. British India then included modern-day Pakistan, Myanmar and Bangladesh.

In recent weeks, a campaign to see Second World War intelligence heroine Noor Inayat Khan put on a UK bank note has also gathered significant attention.

She helped to run British radio communications behind enemy lines before being killed in a Nazi concentration camp in 1944.

Mr Ferrier points to a canvas that depicts Muslim and Christian soldiers praying just metres apart.

“I don’t know what happened the day before or the day after, but I know what happened in that moment – it’s beautiful,” he says. “Enjoy that moment.”

He is also keen to stress that although this is an exhibition about a conflict that ended almost a century ago, it is as much about the present and the future as it is the past.

“The emotions you see here are the same as were there in the Second World War. I hope people come to the exhibition, listen, read and then take it back with them”.

When Laurence Binyon's For the Fallen was published in a British newspaper in 1914, he might not have known that a single stanza would become the ode through which much of the western world remembers perhaps the most devastating conflict of the 20th century.

“At the going down of the sun and in the morning, we will remember them,” reads the tribute. Its familiarity in Britain and across Europe is near universal.

Now Britain is grappling with the question of exactly who is being remembered or, perhaps more importantly, who has been forgotten.

The Singularity of Peace is on at The Waterfront Building in Hammersmith until November 18.