Rivers of vapour in the sky caused an enormous hole to form in the Antarctic sea ice three years ago, according to a new study led by researchers at Khalifa University.

Published in the journal Science on Tuesday, the study shows how atmospheric rivers created a hole four times the size of Dubai, and explores what this could mean for rising sea levels.

Atmospheric rivers are narrow ribbons of fast-moving air that can increase temperature over thousands of kilometres.

They attracted attention from scientists in recent years after being identified as a cause of extreme polar ice melt in Greenland, something that raises global sea levels.

These atmospheric changes are an early indicator of how the Earth’s climate is changing, said Dr Diana Francis, the project’s lead researcher.

“The atmosphere transports these changes very quickly around Earth because changes in the atmosphere happen in the timescape of days, whereas changes in the ocean happen in the timescape of years and changes in the ice sheets happen in decades,” she said.

“It is very important because it will give an indication as to what is occurring in the ocean in a shorter time scale.”

Scientists previously studied the effect of atmospheric rivers on land ice in spring and summer.

The Khalifa University study, which was supported by Masdar Abu Dhabi Future Energy Company, showed how atmospheric rivers can also drastically change sea ice levels in winter.

Sea ice is an important barrier that stops glaciers from crashing into the sea. It is a first line of defence to insulate land ice and stop sea levels rising.

“We know that the sea ice is very important because it works like a buffer to slow the flow of land ice to the ocean,” Dr Francis said. “If our sea ice is reduced, then land ice is free to flow into the ocean and contribute more to the sea level rise.”

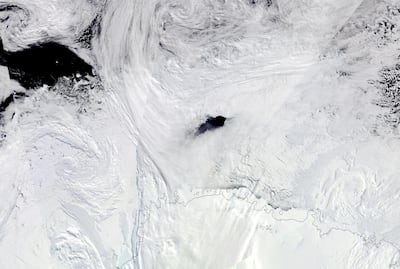

Researchers investigated the appearance of a strange hole in the Antarctic’s Weddell Sea in September 2017, a time when the sea ice is usually thickly packed.

The hole was initially attributed to seasonal cyclones but was recorded only once before, in 1973.

Dr Francis went through satellite data from 1979 to 2019 to look for abnormalities. She discovered that an atmospheric river appeared four days before the gap emerged in 1973 and 2017.

It lingered for four days, triggering a thaw in the sea ice that made it vulnerable to breaking when a severe cyclone hit hours later.

Atmospheric rivers also inhibited ice refreeze at night, which helped to keep the hole open.

Later that month, more atmospheric rivers appeared and enlarged the opening, until it had grown to about four times the size of the emirate of Dubai.

When researchers checked this against high-resolution data from 1973, they found the same pattern.

This rare event could become more common, Dr Francis said.

Atmospheric rivers have become more common and more intense in polar regions owing to climate change.

They can have significant impacts in these normally arid places, with consequences for Antarctica’s wildlife.

Areas free of sea ice, known as polynyas, play a vital role in the food chain, said Thomas Mote, a specialist in atmospheric sciences and climate change at the University of Georgia in the US.

“We expect that stronger atmospheric rivers will reach Antarctica more frequently and bring even more moisture in a warming climate,” he said. “Polynyas serve an important role in the Antarctic ecosystem but we don’t have a good understanding of how changing weather patterns may affect polynyas in the future.

“We need to understand how these changes in weather will affect sea ice and this paper is a starting point in that direction.”