From crash-landing a hypersonic aircraft to bringing a wildly spinning spacecraft under control, there's plenty of action in First Man, the blockbuster biopic of astronaut Neil Armstrong, now showing in cinemas.

At one point, Armstrong - played by Ryan Gosling - is facing so many challenges during his historic landing on the moon that it all seems a bit far-fetched. Computer alarms are going off, the radar keeps bugging out, there’s virtually no fuel left - and Armstrong still can’t find anywhere to touch down safely.

And it’s true that the movie bends the facts. The reality was worse.

Mission Control kept losing contact with the Lunar Module (LM), which in any case was so distant that every communication took 2.5 seconds to make the round trip. The movie brilliantly conveys the sheer audacity of Armstrong’s achievements, all made using technology over half a century old.

But the film also holds lessons for those who think 21st century technology is smart enough to trust with, say, driving a car.

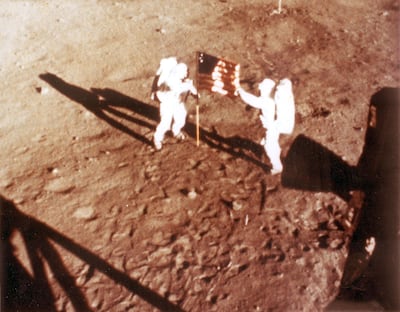

By today’s standards, the computing power used to make Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin the first men on the moon is risible.

A cheap pocket calculator packs a bigger punch. Certainly it could have spared the two astronauts the alarms that kept flashing during the descent – the result of the primitive on-board computer being overloaded.

But even today’s computer technology can be undone by a problem that nearly killed Armstrong and Aldrin: GIGO – garbage in, garbage out.

________________

Read more:

Lunar eclipse witnessed by millions in UAE and worldwide – in pictures

________________

It’s at the heart of a mystery the movie dodges: how, despite all the planning, practice and dry runs, did Armstrong and Aldrin still end up staring disaster in the face?

The Apollo programme cost over $200bn in today's money, and was arguably the most complex engineering project ever undertaken. It was also unprecedented in the determination of those involved to think of everything.

From using fuels that didn’t need ignition systems to predicting deadly radiation storms from the sun, America’s best and brightest dealt with every conceivable threat.

Almost. As the LM came into land, Armstrong saw the landing-site was a huge crater, with car-sized boulders around it.

This was not in the plan. Mission planners had spent years pondering the safest place to make the first manned landing. They scoured the best earth-bound telescopic images. Then they sent low-flying probes over the Moon which were able to take images of objects as small as a metre or so across.

After one last check using images from Apollo 10 just weeks before the historic mission, the perfect spot was found on the Sea of Tranquillity: well-lit, dead flat and clear of obstacles.

So how did everyone miss the huge boulders and crater the size of a football field?

They hadn’t. Even before the final approach, Armstrong had noticed they were shooting past landmarks earlier than expected. For some reason, the LM was travelling faster than anticipated, and had overshot the planned landing site. But the on-board computer was doggedly sticking to the original flight-path.

Realising that disaster loomed, Armstrong took over the controls, and began a desperate search for a clear site.

After several anxious minutes, with computer alarms flashing and barely any fuel left, Armstrong found a spot, pulled off a perfect landing – and the rest is history.

But Nasa’s mission controllers knew tragedy had only narrowly been averted, and set up an urgent inquiry. With Apollo 12 scheduled to launch just a few months later, they had to discover what they’d missed.

The culprits were two subtle but potentially deadly effects no-one had thought of.

The first was the result of the LM detaching from the mother ship to make its descent. As they separated, air seeped out from the tunnel that had connected them. This gave the LM a light push – and nudged it off the expected trajectory.

The second culprit was lying hidden beneath the moon’s surface.

The year before the Apollo11 mission, astronomers found evidence of colossal chunks of rock buried deep in the Moon. Known as mascons – for “mass concentrations”, their origin was unknown. But their huge mass distorted the gravitational field of the Moon –and pulled the LM dangerously off-track.

By the time Apollo 12 headed to the Moon, Nasa’s engineers had found solutions so effective the LM landed just metres from its target.

But the fact remained that they had tried to think of everything that could possibly go wrong – and had failed.

The reason Apollo 11succeeded was because Armstrong realised something was wrong, and seized control from the computer.

And that was only possible because the engineers had a backstop for their lack of omniscience. They never felt comfortable giving computers total control of the descent, so they gave the astronauts the option to take over at any time.

Armstrong proved the wisdom of that – so much so that later missions made it even easier for the astronauts to seize control.

Yet half a century later, engineers seem to have fallen under the spell of computer power.

Just last week, car-makers General Motors and Honda announced plans to work together on a vehicle with so-called Level 5 autonomy. That is, humans do nothing apart from get in and give the destination. There’s no steering wheel, pedals or gear-stick.

We can only speculate what Armstrong – an engineer himself, as well as test-pilot turned astronaut – would have made of such confidence in computers.

Still, perhaps the creators of such cars truly believe they can do better than America’s finest did on Apollo, and really can think of everything.

Robert Matthews is Visiting Professor of Science at Aston University, Birmingham, UK