It is the strongest material known to man, more conductive than copper and more flexible than rubber.

But while the scientists who discovered graphene in 2004 won a Nobel Prize for finding the new “wonder material”, for years, no one was quite sure what to use it for.

A decade after scientists at the University of Manchester in the UK discovered the atom-thick substance with a simple experiment using sticky tape, The New Yorker magazine proclaimed it "fast, strong, cheap ... and impossible to use".

But all that is changing with the help of investment from Abu Dhabi.

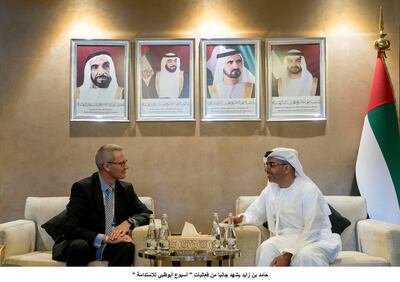

James Baker, chief executive of Graphene@Manchester, said work at the £60 million (Dh288m) Graphene Engineering Innovation Centre, which received half its funding from Abu Dhabi renewables company Masdar, is helping to ensure the material reaches its world-changing potential.

Graphene is already used in sportswear and equipment, making tennis rackets and footwear lighter and more durable.

But in the years to come, graphene could be crucial in areas such as water desalination and electric planes, Mr Baker told The National at Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week, where he travelled to promote the material in the Middle East.

"In the next two to five years, we'll see graphene making a bigger social impact," he said. "What I think you'll see from 2020 and beyond is a real increase in terms of new products, new applications, hitting the marketplace."

The funding from Abu Dhabi is helping graphene through what Mr Baker calls the valley of death – the period between discovery of a new material and the point at which it becomes cheap and easy enough to manufacture that it is widely used across the world.

It took around 25 years, he said, from the discovery of high-performance carbon fibre before it was used in everything from bicycles to Formula One cars.

Graphene, Mr Baker said, could one day be a vital component in self-charging electric cars and even electric aircraft, helping to reduce carbon emissions.

Researchers have already developed a small graphene filter capable of making seawater drinkable, an innovation that if replicated at scale could be used in large-scale desalination plants or in poor countries where clean water is scarce.

Researchers at Khalifa University in Abu Dhabi are also working on using graphene for desalination.

“The analogy we often use is chicken wire,” Mr Baker said. “You can layer it so some molecules will pass through but block others. For water, salt molecules are large, whereas water is quite small.

"You can arrange the layers so water can pass through but they will block larger contaminants. Today, we can do that with an A5-size membrane, maybe A4, which is great for a lab. But we need to do that by a metre squared, a kilometre squared – that's the challenge."

It has also been found that by adding graphene to old tyres, plus a small quantity of new rubber, they can be returned to their original performance.

Mixing graphene into concrete means 20 per cent less concrete can be used without any loss of strength.

The substance is soon to hit a tipping point, Mr Baker said, where use will become widespread. He believes there are investment opportunities, and as production methods advance, the use of graphene will become ubiquitous.

In Abu Dhabi, he said he had even begun discussions about making a better tasting non-alcoholic beer, which could have appeal for Muslim countries. The beer would be brewed normally, he said, but a graphene membrane could then be designed to filter the alcohol out, meaning less impact on taste.

“Generally, when you make non-alcoholic beer you affect the taste and it’s not very nice,” he said. “How can make non-alcoholic beer taste good? You make alcoholic beer then you take the alcohol out. There is some dialogue — can we use a graphene membrane to make non-alcoholic beer?

“Graphene comes in many shapes, sizes and forms. Strictly it’s one layer, but there’s now a standard up to 10 layers. It’s a bit like Lego blocks, you can assemble it in infinite ways.”