Inside the brown box of the World Trade Center Mall, boys in rows of replica F1 race cars stare at virtual tracks on video screens.

Across a cobbled road at The Souk, young Emirati women shop at Barbie Shaila and Abaya and nibble petits fours at the Shakespeare & Co teahouse, seated on frilly pink pillows and green velvet couches.

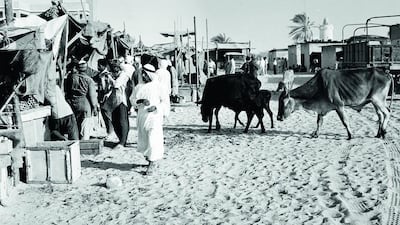

Fifty years earlier, Brahman cattle swaggered on this spot over thick white sand, past a jumbled collection of stalls built from rickety poles and tarpaulins. The tallest landmarks were palm trees and the thick minaret of the Otaiba mosque. Here, near Qasr Al Hosn and the British customs house, merchants sold their goods in a market that would later become the city's open souq between Hamdan bin Mohammed Street and Khalifa Street.

The souq was one of the first projects completed for the Abu Dhabi master plan, commissioned by Sheikh Zayed in the early 1970s and overseen by Dr Abdulrahman Makhlouf, who recently recalled the 200-shop market as one of his first and favourite projects.

It stood for nearly 30 years until it was gutted by fire in 2003 and demolished two years later. Construction on the replacements – The Souk and the World Trade Center – began in 2007. The Souk opened in 2011 and the WTC Mall last month.

Some cities have layers. In Abu Dhabi, a city built on sand and sea, history is not kept in buildings that are quickly rebuilt and reinvented, or in people, who pass or fly away. History is preserved through action.

When the old souq closed, the merchants stayed. They were splashed across town, hidden in alleyways and markets off Hamdan Street and the Madinat Zayed Shopping Centre.

For them, the physical building is not what counts. It is enterprise that makes a market, not bricks. As far as the shopkeepers of Hamdan Street were concerned, the old market never closed. It shifted.

You’ll find traces of the original souq around its old neighbourhood. There are physical remnants, like the pedestrian bridge that links The Souk to the 160-shop World Trade Center Mall, in the same place as a bridge that linked two original markets. More telling are the people scattered around the area: squatting cobblers battering leather soles, coconut hawkers slicing thirst-quenching shells,

and men renting bathroom scales. Tradesmen who once roamed the open market are still found around the city.

Labourers travel from Mussaffah and Baniyas to the famous Hamdan Street shops that survived the market fire and moved across the road, such as Abdul Bari Garments and Gifts Shops and Seastar Electronics Trading, a

piece of the old Iranian embassy compound

.

They sell the mishmash of the old market that made it a one-stop shop: razors, fans, plastic fake gold jewellery, prayer mats, gum, socks, bukhoor-scented perfume, thermoses, hair clips and mechanised blonde dolls with blinking eyes.

Sales have dwindled with new shopping malls. Mohammed the Keralite, a salesman at Abdul Bari, calls his remaining customers the muskeen, or unfortunates. “People all go to the hypermarket,” he says. But there are hidden shops that lure back people of all incomes.

In the wedding season, Emirati grooms go to an ageing high-rise beside the Central Market and up a narrow escalator to Abu Dhabi’s oldest kandura shop, Abu Haliqa. Mohammed Alam Ansari, 55, a salesman from New Delhi, has clothed Abu Dhabi’s grooms in bisht cloaks since 1987. “Everybody needs a bisht,” says Ansari.

When he arrived in Abu Dhabi in the 1980s, the souq was well established and the city had grown around its one and only market. The shop had opened at the central market decades earlier, he says.

“For Pakistanis and Emiratis, for ladies and gents. If you want thread, if you want needle. If you want gold, if you want watches. Everything was in this market,” says Ansari.

“1987 Abu Dhabi and emirate is in progress. Not like before, in dust. When I came here I see all beautiful city, tallest buildings, neat and clean.”

Abu Haliqa was the first Abu Dhabi kandura and bisht shop, and customers came from the Empty Quarter and Saudi border towns. “Morning I would open eight o’clock and maybe 20 or 30 people were waiting outside because nobody sold these items before. Now maybe there are 1,000 shops like this.”

As he speaks, a 20-year-old walks through the door for an agal fitting. He has travelled an hour, on his father’s orders, to find Abu Haliqa.

Men like him wandered through the open souq when they were boys, listening to a soundtrack of Bollywood, Pashto and Malayalam hits. Music-makers such as Qudrat Ullah Malak competed for customers by blasting the melodies from their shops.

Qudrat Ullah Malak is around the corner from the current Abu Haliqa shop in a Hamdan Street alleyway. He hawks cassette tapes of Malayalam classics and Christmas carols he’s sold for decades. He works from a glowing doorway framed by fluorescent lights. Perhaps in tribute to the music he once blasted from his shop, a large speaker is attached above the door frame beside a sign that reads: Shaan Radio Center.

Malak, 59, works under a stairwell in a space so narrow he must turn sideways to walk in it. Sales are made from a desk at the door, half a block from where he worked at Shop 18 in the old souq.

“All these young men in the offices, they know me,” he says, pointing to glassy skyscraper offices above. “In any market I am famous. I two times shook hands with Sheikh Zayed. All Arabs know me.”

Even amid the Gulf shopping-mall culture, where malls function as town squares, customers prefer the old market shops to The Souk and other new malls.

“It [the old market] was beautiful,” says Ramesh Surya, a 45-year-old engineer from India, who has lived in the UAE since 2005. “You feel like it’s a home next door and the home next door is a second home.”

“That’s the main thing, the welcome and the warmth,” agrees his friend, a 50-year-old chartered accountant who moved to Abu Dhabi in 1999. “They were selling everything. It was a common man’s place.

“It was covering all nationalities. Moreover it was open. In a mall culture you’re moving from a small flat into a big flat.”

With only one place to shop, the community was larger in its unity: Westerners, Asians, Arabs and Emiratis, sheikhs, professionals and labourers – all shopped at the souq.

Around the corner from Malak’s store was the jeweller Tariq Mubarak, one of the men who made the souq sparkle. Both relocated but are still within sight of each other across Hamdan Street.

Mubarak, now 49, was the first of six brothers to set foot in the UAE. He left his family’s goldsmith shop in Lahore at the age of 15, hopped a train to Karachi and boarded the next Dubai-bound boat for a 1,000 rupee fare. It was winter, 1975. He could not swim. “Everything is water. We [were] afraid too much.”

He waited for opportunity. “In my school, my friends told me this country was very nice and there is too much future,” says Mubarak.

He landed at the Abu Dhabi souq after a fruitless week in Dubai. He remembers a market of 10 or 12 shops. “Everywhere is only sand, sand. No buildings, uh? Too much big change, uh?

“My friend told me go to Dubai, go to Bahrain, go to Muscat but my heart is in Abu Dhabi. I liked it. There people is very nice and all area is very open open, not congested.”

Customers crowded the gold shops in the 1980s to buy gold bars and simple chains. Mubarak’s older brother Sajjad Ali joined him after two years. The brothers couriered a bangle manufacturing machine and casting machine from India, bought small tools in Dubai and started a showroom. They had two more by 1982 in shops 16, 18, and 63.

“You know day by day, day by day, Abu Dhabi [got more] popular and people came here and started their businesses,” says Mubarak.

“So we are too happy about this government and this place because in the old market, they were all countries and all kind of people. Cheap, expensive, medium. Everything we get from there. All kinds of people. Poor people, rich people, middle people came to there and everything they got from there in old market. Mix market is very nice, huh?

“So when we heard that this market would be demolished I was too much scared. Where we go?” They lost half their business when they moved after the fire but the shop, a rose-scented showroom of glass and gold with the names of God painted on its walls, still exists.

“Everybody came. Souq is famous. Very cheap and very popular. Now there are so many malls but before only the souq was famous.”