Mangroves are estimated to cover more than 150 square kilometres of the UAE's coastline, acting as a "green lung" for big cities such as Abu Dhabi and Dubai, while also providing habit for wildlife and recreation grounds for humans.

Most of us would see mangroves as a beautiful element of our landscape - a natural fringe to our developed urban environment, where flamingos flock together and fish and crustaceans proliferate.

But how much do we really know about the complexity of our mangrove ecosystems?

Two biologists from New York University Abu Dhabi, Shady Amin, assistant professor of biology and Guillermo Friis, a postdoctoral associate in the marine biology lab, help us understand the truly incredible ecosystems which are on our doorstep – or for the lucky, in view of our apartments.

What is a mangrove and why are they special?

Mangroves are woody plants that inhabit the intertidal zones of tropical and subtropical coasts all around the world.

They are highly recognisable from their visible root systems which can give them the strange impression of being planted upside-down.

This unique appearance is the result of adaptations developed to survive in harsh environments, including high temperatures, high salinity and intense UV exposure.

The most noticeable feature, the aerial roots known as pneumatophores, help the plant cope with growing in oxygen-deprived sediments, and also physically stabilise these soft sediments.

Mangroves are able to accumulate and excrete salt in their roots and leaves in order to exist in marine environments.

They are also viviparous, meaning that their seeds begin germinating before they fall from the parent tree, which increases the chance of successful rooting in tidal environments.

The dominant species in the Arabian Gulf region is the gray mangrove (Avicennia marina).

Dr Friis said the ecological conditions which mangroves thrive in are particularly extreme in the region, both in terms of salinity and temperature variability.

“Mangroves are the only evergreen forest in the Gulf and their unique ability to survive in this habitat makes them what we know as an "ecosystem engineer", providing shelter and foraging to many marine and terrestrial species,” he said. “In addition, different biological, chemical and physical processes connect mangroves to adjacent ecosystems including coral reefs or seagrass meadows.”

How do mangrove ecosystems work?

As primary producers like land plants or sea-dwelling phytoplankton, mangroves are photosynthetic organisms that can convert sunlight into energy.

This in turn is used to transform carbon from carbon dioxide gas produced from burning fossil fuels, into organic carbon that feeds the plants themselves and the entire ecosystem they exist in.

Positioned between the open water and shorelines, mangroves provide habitats for many species including oysters, phytoplankton, sponges, crabs and other organisms.

“Because of their ability to fix carbon dioxide into organic carbon and because of their ability to form complex root systems, they can support dozens of different species,” Dr Amin said.

The relationship is symbiotic, with mangroves depending upon the organisms they support to support them in return.

“For example, mangroves cannot survive without microbes living around their roots just like we cannot survive without microbes in our gut that help us digest food,” Dr Amin said.

“One of the main things microbes provide for mangroves is nitrogen, a required element to make DNA and proteins.

“For example, some microbes are symbiotic with mangroves and are able to convert nitrogen gas into ammonia, the main constituent of agricultural fertilisers. This ammonia then allows mangroves to grow just like they do with trees.”

Other types of microbes in the mangrove ecosystem include sulfate-reducing bacteria that thrive in the oxygen-deprived environment, and organisms that produce methane.

“No organism on earth lives in isolation and all these microbes, the mangrove and other higher organisms like algae and crabs are interacting with each other,” Dr Amin said. “It is these interactions that truly form a healthy ecosystem”.

What wildlife do the UAE’s mangroves support?

Mangrove forests support a high level of biodiversity and the UAE’s are no exception.

“To name a few of the species we can find, in the UAE there are reports of six different families of crabs; 49 mollusc species including clams and marine snails; examples of both residents and migratory birds like the Western Reef Heron or the Greater Flamingo; and numerous roving fish populations,” Dr Friis said.

“If we are lucky, we can also find ray fishes hiding under the sand, or even blacktip sharks that occasionally enter mangrove swamps.

“There are also large communities of fungi, algae and bacteria associated with the mangrove ecosystems.”

However, Dr Friis said there had been relatively few studies documenting UAE mangrove wildlife and further research was needed.

How do mangroves benefit humans?

Because of their ability to sequester carbon, one of the major benefits of mangroves is their ability to reduce harmful the greenhouse gases which cause climate change.

“They basically convert this greenhouse gas into organic carbon that is either released into the surrounding sediments or is used to build their complex root structures,” Dr Amin said. “This is useful because the more carbon dioxide we put into our atmosphere, the more we suffer from climate change consequences.”

Mangroves also protect coastal areas from erosion by creating a buffer zone, filtering and pacifying tidal flows, and can even reduce the damage and loss of life caused by tsunamis.

“For the UAE and with increasing sea level rise, mangroves are essential because I expect they will play an important role in protecting our shorelines from erosion,” Dr Amin said.

A number of commercially important fish and shrimp species use mangroves as nursery habitats. And, historically, mangroves also provided fodder for livestock and served as an important building material in pre-oil times.

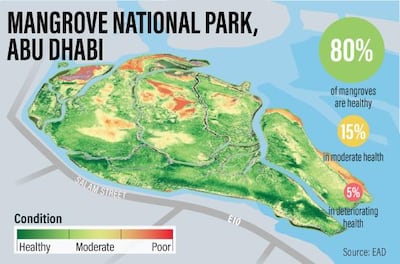

On top of all of these benefits, mangroves provide recreational grounds, as demonstrated by the Mangrove National Park in central Abu Dhabi.

“They are part of the heritage of the country, and one to be protected,” Dr Friis said.

Could mangroves be the secret to treating cancer?

A lesser-known potential benefit of mangroves lies in the microbes they co-exist with. At NYUAD, scientists are working to isolate and identify unique molecules produced by the microbes in mangroves that could have potential to tackle human diseases including cancer and pathogenic bacteria.

“We find more potential anticancer molecules produced from mangrove associated bacteria than researchers have found in most other marine habitats,” Dr Amin said.

How much of the UAE is covered in mangroves?

Estimates of mangrove coverage in the UAE vary, with the Environment Agency Abu Dhabi, which uses high-resolution satellites to map the emirate's mangroves, putting their area at about 155 square kilometres.

That figure is believed to have nearly doubled over the past 20-30 years as a result of plantation and rehabilitation projects first initiated by Sheikh Zayed.

How can we protect our mangroves?

There are several key threats to mangroves, including urban expansion, limited fresh water resources and pollution and physical damage from humans.

“Coastal development is an important objective of human civilisation but if not done properly, it could severely harm these ecosystems, which in turn harm us on the longer time scale,” Dr Amin said. “Although we can remove mangrove forests and re-plant them elsewhere, the fact that we are only planting mangrove trees without all the other microbes and higher organisms that are essential for mangroves means we are basically creating 'zombie' trees that can never flourish.”

Dr Friis said sustainability was gaining weight in policy making in the Gulf, which provided an opportunity to introduce ecological considerations into urban development.

“Favouring the plantation of mangroves as soft defence structures to dissipate wave energy instead of breakwaters and seawalls would be an excellent way of preserving them while meeting urban development needs,” he said.

When it comes to individuals, the best thing citizens can do is remember that our habits always have an impact on the natural environment.

“More efficient use of water and energy in our daily lives, and of course being respectful when visiting the mangrove forests, can help to protect this ecosystem,” Dr Friis said.

Both scientists agreed that ecotourism activities such as kayaking are good ways to enjoy mangroves while having minimal impact. But people should be careful not to stand on the roots of plants, or the surrounding sediments. Also avoid making loud noises that can disturb foraging and nesting birds.

“The diversity of wildlife in mangroves is amazing and is worth exploring. But we must be careful not to tread too heavily as to destroy it,” Dr Amin said.

This article was first published on 12 April, 2019