A twin-propeller Beechcraft KingAir C90 takes off from Al Ain Airport, soaring into the skies above the country. The pilot manoeuvres the plane into position under the base of a cloud. Salt flares attached to its wings are fired, and now meteorologists wait and hope.

This is just a typical day for the UAE’s cloud seeders and Wednesday’s awards for rain enhancement has brought their programme into sharp focus.

In a country with an annual rainfall rate of about 100mm, high evaporation of surface water and depleting groundwater reserves, it’s not hard to understand why it was established.

Run by the National Centre of Meteorology, seeding began in the 1990s. By the 2000s, the NCM were working with global peers such as Nasa and the National Centre for Atmospheric Research in the United States. Last year it conducted 242 missions, while 177 were undertaken in 2016.

Water security is a global issue. According to the United Nations, about 1.2 billion people live in areas of physical scarcity. Cloud seeding could yield more water for crops, boost supply and recharge wells. Another advantage is that seeding is significantly cheaper than desalination. About 60 times cheaper to be precise.

Cloud seeding is simply a way of trying to extract more rain from a cloud.

An operation begins in the early morning with meteorologists monitoring the clouds.

Those suitable for seeding are warm clouds or convective clouds technically known as cumilform that have an updraft in the middle.

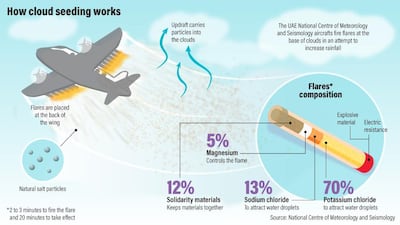

Fortunately they are the most common type of cloud found in the UAE. When these can be seen on radar, pilots are sent to the location and salt flares are fired into the updraft.

These particles attract tiny droplets of water and also encourage condensation. The droplets then collide with others, become larger and eventually fall to the ground as rain. The cloud can also become larger due to this activity.

When rains lashed the country in March last year, much of the coverage about the flooding incorrectly focused on the cloud-seeding operations that had taken place. Seeding only attempts to enhance rainfall.

“If clouds show signs of heavy rain, and those likely to cause floods – we do not undertake cloud-seeding operations,” says Sufian Farrah, cloud-seeding specialist at the NCM.

Summer is an important time for seeding with the operations running four days a week from July to September.

The NCM’s six planes are based at Al Ain airport because the best clouds for seeding form along the eastern coast. Only natural salts are used. When I ask Dr Deon Terblanche, director of research at the World Meteorological Organisation about ethical concerns, he rejects this.

"When you look at nature, there is almost not a part of it that's not been impacted by humans. If you practice agriculture, you change the landscape and use fertiliser and pesticides. You have new varieties of plants," he said.

"This is how we as humans use our knowledge and expertise to make the planet more habitable. But if you try to apply the technology for the wrong reasons, then it's not a good idea."

But the link between seeding and how much rain fell is, and always has been, hard to quantify. In 1946, US meteorologist Vincent Schaefer coaxed snow from a cloud using dry ice. During the Vietnam War, the United States tried to seed clouds to extend the monsoons and disrupt enemy lines along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, while more recently the Chinese tried to prevent rainfall during the 2008 Olympics. It’s been difficult to tell if the US or Chinese bids actually worked.

According to the NCM, seeding can boost rainfall from an individual cloud by as much as 35 per cent in a 'clean atmosphere'.

"Based on our previous seeding operations, we estimate that cloud-seeding operations can enhance rainfall by as much as 30 to 35 per cent in a clean atmosphere, and by up to 10 to 15 percent in a turbid [dusty] atmosphere,” said Omar Al Yazeedi, director of research, development and training at the NCM.

Because the UAE's atmosphere can be hazy, the lower figure is more usually representative of the seeding operations here.

But it’s still difficult to determine how successful the operations are and it’s not a case of simply looking at rainfall.

“Rain gauges will help but some clouds are between 8 to 10 kilometres between each rain station. So the size of the droplets can be monitored through radar reflectivity,” says Mr Farrah.

But research is pouring into the field and is being led by the UAE Research Programme for Rain Enhancement Science.

“One project supported by the programme has already filed a provisional patent with the United States Patent and Trademark Office in February this year for a new application of nanotechnology to cloud seeding,” said Mr Al Yazeedi.

The NCM also conducted a randomised statistical experiment in the summer of 2003 and 2004. Some clouds were seeded and some not, and afterwards the NCM sat down to assess the more than 150 weather cases that were recorded.

“These cases are analysed between those that are seeded or not – radar data shows the water in the cloud and how the updraft increases or not. More condensation means a bigger updraft,” said Mr Farrah.

“It’s still in research mode and therefore the awards are here. More investment in cloud seeding will give us an advantage.”

____________

Read more:

Rain enhancement pioneers win UAE's $5 million award at Abu Dhabi Sustainability Week

Seeding flights in UAE 'boosting rainfall from clouds by a third'