AL GHARBIA // Covered in a layer of fine sand, the remains might not appear much to the untrained eye. But for scientists it is an important piece of an ancient puzzle.

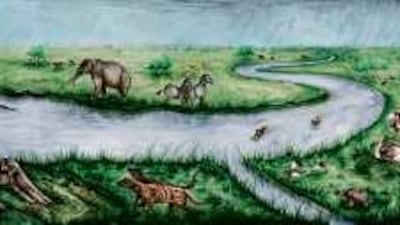

An eight-million-year-old crocodile skull found recently on a remote site in Al Gharbia will help paint more detailed pictures of how life would have looked back then. Millions of years ago, this part of Abu Dhabi was a lush oasis of savannah-like vegetation populated with creatures such as three-toed horses, monkeys, squirrels, elephants, hippos and even a sabre-tooth cat roaming the landscape.

An outline of what life was like in Arabia during the late Miocene Epoch is getting richer with details every year because of the work of a team of local and international scientists. However, members of the team say their work is being threatened by factors such as development and exploration for natural resources. The National visited the team at a remote site in Al Hadwaniyyah, approximately a two-hour drive from Abu Dhabi City, on Wednesday, two days before their field work for this season was scheduled to end.

The experts were attempting to learn more about the species that they know once existed here. "There is one kind of elephant-like creature from which we only have a bit of tooth," said Andrew Hill of Yale University, who has been coming to the country to study Al Gharbia's Miocene fossils since 1989. "It will be nice to find at least a whole tooth." A complete bone can tell how slender the animal was. This type of information can help scientists theorise its behaviour. Identifying fossils involves having a strong knowledge of the anatomy of modern animals as well as studying records and samples of fossils obtained from the same period in other parts of the world.

"The ideal thing will be a whole jaw or a head of an animal but they are rare," Prof Hill said. "Whole teeth are good because you can measure them and deduce the size of the animal." The five-year expedition is a collaborative project between Abu Dhabi Authority for Culture and Heritage (Adach) and the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University. This year, the effort is helped by scientists from the University of Poitiers in France and another American university, the Western University of Health Sciences.

"It is like a treasure hunt but with some rules that let you know where to look and where not to look," said Faysal Bibi, a palaeontologist from the University of Poitiers, on what it takes to spot fossils. All of Abu Dhabi's Miocene sites, currently numbering more than 40 locations, are located within a geological formation known as the Baynunah Formation. The Miocene Epoch dates from roughly 23 million years ago to five million years ago. The Alps and Himalayas were formed during this time.

Although some sites in Abu Dhabi are as deep as 55km into the desert, most are along the coast, on hills and outcrops along a nearly 200km stretch of the shoreline, from Rumeitha to Jebel Barakah. "A lot of our work depends on finding things on the surface," said Dr Bibi, explaining that fossils come to the surface through the erosive forces of wind and water that clear away sediment. If something interesting is spotted, the location is marked with a small flag. Once the initial survey is completed, the team returns to the marked spots, records the co-ordinates with a GPS device and collects the fossils, if any.

"It is a lot of walking," said Dr Mark Beech, a cultural landscapes manager in the Historic Environment Department of Adach. "It is painstaking work. You have to be patient and very sharp-eyed." It turns out the crocodile skull, one of the expedition's most interesting finds of the season, could easily have been overlooked. Most of the fossils were found along elevated areas; the skull was languishing on lower ground.

"We were even thinking of skipping this area," Dr Bibi said. Everything else has come from a higher level.". Even without a picture of the creature's modern cousin, it is easy to see the white outlines of the skull of a crocodile's head. They believe the ancient crocodile is closely related to species living in the Nile River today. "Reptiles evolve very slowly [compared to mammals], so this is not surprising," Dr Bibi said.

Once Dr Bibi has dug around the skull, it is time for Dr Mathieu Schuster, a sedimentologist from the University of Poitiers, to begin looking for clues. By examining the type of soil and other features, Dr Schuster can make conclusions about the context of the fossil find. Meanwhile, after having cleaned the upper layer of the skull with a small brush, Dr Bibi applied liquid glue to the bone surfaces. This, he explained, is necessary so they do not break when they are taken out of the sand. After each layer of sand is cleared, bit by bit, Dr Bibi will wrap the skull in a thick layer of wet tissue and build a casing from plaster gypsum. The procedure lasts several hours and when it is completed the find can be taken to a lab for further study.

Large creatures such as crocodiles and elephants are only one part of the story. To get a full picture of the rich ecosystem that once existed in the ancient oasis, Dr Brian Kraatz, an assistant professor of anatomy and a specialist in microfauna at the Western University of Health Sciences, is using a keen eye to study the smaller species."It is a lot more difficult to find the small animal and it requires different methods," he said. "What we spend the most time doing is try and figure out which pockets of sand to look for."

One of the discovered items is a cheek tooth of an ancient cane rat, an animal that was about the size as a small cat. To the naked eye, the fossilised tooth looks like a large grain of sand. It is only when viewed under a magnifying glass that details become clear. "This is a big one," said Dr Kraatz of the specimen which measures 2.5 by 3 millimetres in size. The contents of two small sealable plastic bags and a tiny box are "essentially two seasons of work," he said.

Al Gharbia's fossils will one day be displayed at a museum dedicated to palaeontology that Adach plans to complete in 2013. Meanwhile, protecting the fossil sites is an urgent priority for the scientists. The Al Gharbia coastline is important to the military and for oil and gas exploration. The development of tourism and infrastructure projects brings additional urgency to protect the sites. "We are losing these sites," said Dr Bibi. "That is why it is really important to start thinking seriously about putting some of them aside."

Dr Beech expressed a similar opinion. He said co-ordination exists between government departments and developers, but more needs to be done. "The speed of development is quite fast," he said. "The key fossil sites all need to be fenced off. We really should have a network of protected fossil-site areas." @Email:vtodorova@thenational.ae