Turn the clock back half a century and the now commonly seen Arabian oryx could hardly be found in the deserts of Abu Dhabi.

Driven to extinction in the wild by hunting, the future looked grim for an animal woven into the culture of the Arabian peninsula through poetry and paintings.

But 50 years on, the antelope with a bright white coat and magnificent ringed horns is thriving in the wild thanks to efforts spearheaded by the UAE.

It is one of many species of animals being brought back from the brink through conservation programmes across the Gulf.

Abu Dhabi's first conservation success story

More than 1,200 Arabian oryx are found in the wild, in countries including the UAE and Saudi Arabia, and thousands more live in what is described as semi-captivity.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature now classifies the animal as “vulnerable”, which is three categories up from its previous designation: “extinct in the wild”.

This is an astonishing success story over such a short period of time.

“The Arabian oryx has been the flagship for the introductions in the UAE,” says Justin Chuven, unit head of ex-situ conservation programmes at the Environment Agency Abu Dhabi.

“That population is growing quite well. There are 800 or so in the Empty Quarter [desert that stretches from the UAE into Saudi Arabia]. The source population has also been used for other reintroductions in Jordan and Oman.”

Environment Agency Abu Dhabi

More than 10,000 of the animals can be found in the Emirates — about half of which are in Abu Dhabi. The oryx population in the Al Dhafra reserve now stands at 946, a 22 per cent increase from four years ago. Al Dhafra was home to just 160 of the animals in 2007, when the Sheikh Mohamed Bin Zayed Arabian Oryx Reintroduction Programme was established.

Although it is the most celebrated, the Arabian oryx is just one of many species, including other mammals, birds and reptiles, being bred in captivity in the Arabian peninsula for reintroduction to the wild, either here or further afield.

In Saudi Arabia, for example, an Arabian leopard cub was born at the Prince Saud Al Faisal Wildlife Research Centre near Taif in the south-west of the country in April. The Royal Commission for Al Ula (RCU), which runs the breeding programme, ultimately hopes to reintroduce the endangered subspecies — which is extinct in the UAE — to north-west Saudi Arabia.

How species are selected

When deciding which creatures to focus on, a central role is played by the classification system of the IUCN, a Swiss-based organisation, whose president is Razan Al Mubarak.

She is well known in the Emirates as managing director of EAD and the Mohammed bin Zayed Species Conservation Fund.

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species places species and subspecies in one of seven categories − from “least concern” to “extinct”.

In categorising an organism, the IUCN considers how restricted the geographic range is, the population size and how it is changing, and whether studies have indicated a risk of extinction.

EAD focuses breeding and reintroduction programmes on animals in three categories: “endangered”, “critically endangered” and “extinct in the wild”.

While its Arabian oryx programme is much discussed, EAD is also part of the highly successful reintroduction programme for the scimitar-horned oryx, which remains classed as “extinct in the wild”. There are now about 375 individuals wild in the creature’s native Chad.

Breeding centres in Abu Dhabi

EAD has breeding and reintroduction programmes for two other ungulate species not native to the Arabian peninsula — the dama gazelle and the addax — and two others that are — the Arabian gazelle and the Arabian sand gazelle. The houbara bustard, a large bird native to North Africa, has also benefited from an EAD captive-breeding and reintroduction programme.

Much of the work takes place at two breeding centres between Abu Dhabi and Al Ain, Al Faya and Deleika, the latter of which is described by Mr Chuven as being “like a big zoo, it’s just not open to the public”.

“We have a very sophisticated breeding operation going on there,” he says. “We’re breeding them in very carefully curated herds to maximise genetic diversity.

“We’ve gone through a tonne of effort to import those unique genetic differences … They all add diversity to our population and add diversity to the population that we’ve reintroduced in the wild.”

EAD has imported animals from across the US and Europe to add genetic diversity. The animals benefit from careful veterinary care, which includes disease testing and vaccination.

A day in the life at a breeding centre

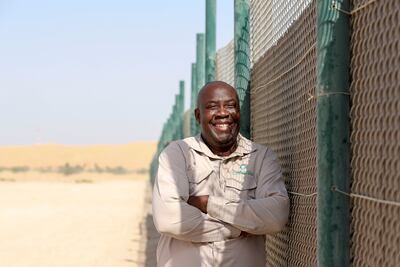

EAD's conservation work is only possible because of a dedicated team of staff at their breeding centre.

Among them is Antony Shoko, the site supervisor and keeper at Deleika. Working under him are staff responsible for feeding and quarantining the animals and for veterinary care.

His is a job with considerable responsibility because under his ultimate care are more than 1,000 animals from endangered species, including the scimitar-horned oryx.

It is not a job for people who struggle to get up in the morning. Mr Shoko’s duties begin at 7am in the winter and run until 3pm. In the summer, work starts even earlier — at 6am — and continues until 2pm.

“My first duty is to make sure everyone has reported for work on time, and we do a safety talk before we start our daily duties,” he says.

“My work continues during the day by making sure that all animals have enough food and drinking water. [Also] checking all animals in case we have had any mortality, a new calf or a sick animal.”

As well as the critical day-to-day business of feeding the animals at Deleika and ensuring that their veterinary needs are looking after, and enjoyable events, such as the arrival of a calf, Mr Shoko is also involved in the translocations.

In fact, he describes this work, which may involve sending scimitar-horned oryx to Chad, as one of the most enjoyable parts of the job.

Deleika Wildlife Management Centre

Looking after animals is about more than simply carrying out a prescribed set of duties. Mr Shoko explains that it also involves trying to understand the creatures and their needs. They may not be able to talk, but there are signs that experienced keepers such as Mr Shoko are able to pick up on.

“We all know that animals do not speak, so that understanding is more important,” he says. “We make sure we give them enough food with enough nutrients.

“I have developed a bond with them because every day they know the time we give them food. If we arrive late to give them food, you see them loitering. It’s their way of telling us that today we are late with their food.”

At the end of another busy day at the centre, Mr Shoko sends a report on events to his manager — and then everything starts up again early the next morning.

How the UAE supports species repopulation abroad

Scimitar-horned oryx and addax, bred in the UAE, are also sent to Chad for release in a reserve that is about as large as the Emirates. The journey is a major undertaking: a six-to-seven hour flight on a cargo plane followed by 10 hours on bumpy roads to the reserve.

The animals are let out into acclimation pens, where they remain for several weeks recovering from the journey and getting used to the feeding habits that will sustain them when they are released.

“The purpose of the project is to have a sustainable number of animals to be breeding by themselves,” says Mohammed Al Remeithi from EAD.

Research indicates that a population of about 500 adults of breeding age is self-sustaining, although EAD hopes to develop more precise figures.

The Covid-19 pandemic caused reintroductions to be paused, but work restarted in November and further reintroductions were carried out in December.

While breeding and reintroducing animals is always complex, Mr Chuven says it is easier with specific species.

“We are very lucky to be reintroducing herbivores,” he says. “They breed very well in captivity. Reintroducing a herbivore is a lot easier than reintroducing a carnivore.”

Herbivores have to learn where food and water can be found, but carnivores have to learn how to hunt. Also, public acceptance of carnivore introductions may not be forthcoming, especially among farmers worried about livestock being killed.

Reintroductions are not just about preserving the species or subspecies that is being set free; they also strengthen the environments into which the animals are released. Native species are less likely than livestock to eat plants down to the roots, and provide food for the likes of vultures, jackals and hyenas, depending on where releases take place.

“The young ones can be taken by jackals,” says Mr Chuven. “It’s going to create an opportunity for the ecosystem to be much more balanced and healthy.”

Sharjah’s Environment and Protected Areas Authority is another organisation breeding wildlife, including reptiles, so that the creatures can be reintroduced into their native habitats.

The conservation of wildlife and natural habitats has been a mandate across the six countries that form the Gulf Co-operation Council since the signing of a convention in 2001, that came into force in 2003.

Animal conservation in Saudi Arabia

In neighbouring Saudi Arabia, efforts are under way by the RCU, to conserve the Arabian leopard.

Listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN, the Arabian leopard's numbers in the wild have fallen to below 200 because of habitat fragmentation, hunting and the depletion of prey species.

At the its Taif centre, the organisation carefully selects breeding pairs to maximise genetic diversity, and employs vets and animal husbandry experts to help build a healthy population that can survive after reintroduction to the wild.

“The RCU are upgrading facilities at Taif, making improvements to leopard enclosures, including the addition of more furnishings, water pools and behaviour-enrichment activities,” says Emma Gallacher, the organisation’s conservation initiatives senior specialist.

On-site staff monitor the leopards and the work is guided by a technical advisory group. Their efforts were rewarded with the birth in April of the female cub. The RCU is designing and building a state-of-the-art breeding centre in Al Ula, just outside the Sharaan Nature Reserve, the area in the north-west of the country where the Arabian leopards will ultimately be released.

“The new centre will follow international best practice and include enclosures where we can see how potential candidates for reintroduction perform in a semi-wild controlled environment,” says Ms Gallacher.

While wildlife in the region continues to face threats, many organisations and their staff are committed to safeguarding threatened species and subspecies for future generations. The workers are rewarded for their efforts in ways that are difficult to quantify.

“There’s nothing that can describe the feeling you get when you see these animals take their first steps on native soil in their native habitat,” says Mr Chuven of EAD.

“You see them out there behaving naturally and you see the calves they’ve produced. It’s an amazing thing to be part of.”