What can you say about Muhammad Ali that hasn’t already been said, when he himself spoke so articulately about his life and experiences? I was just four months old when he and George Foreman rumbled in the jungle. With a fiercely partisan crowd yelling ‘Ali, boma ye [Ali, kill him]’, the one-time champion soaked up fearsome punishment in the opening rounds before dropping Foreman in the eighth.

A year later, those watching travelled back 2,000 years in time, to ancient Rome and its gladiators, as Ali outlasted Smokin’ Joe Frazier in the Thrilla in Manila.

The next four decades were a long, slow fade to black, encompassing defeats to fighters, Leon Spinks and Trevor Berbick, he’d have dispatched in his sleep in the halcyon years. By the mid-1980s, the world knew of the Parkinson’s syndrome. But if anything, the legend only grew.

• More: When Muhammad Ali visited the UAE

• Podcast: Tribute to the most iconic of sportsmen, who changed boxing and the world

The first great boxers I watched were Marvin Hagler, Sugar Ray Leonard, Roberto Duran and Mike Tyson.

Inevitably though, every boxing discussion would veer round to Ali, and his status as The Greatest.

Rocky Marciano had retired undefeated, Frazier had ‘punches that could bring down a building’, and Tyson in his earlier years was just brutal.

But Ali, with the butterfly’s float and the bee’s sting, remained the benchmark. He also redefined sporting fame. When we came back to Kerala in 1986, Diego Maradona was the most feted sportsman in the world. But Ali, who had fought his last great fight a decade earlier – long before television penetrated India’s interior – was a household name.

Whether they called him Ali, or ‘Mammali’, everyone had a vague idea of who he had been.

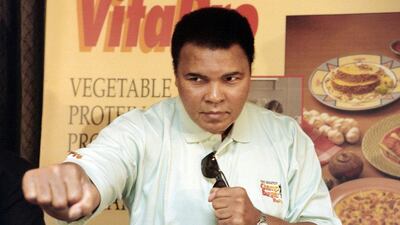

That status was reinforced in 1989 when the Muslim Educational Society (MES) decided to invite him for its 25th anniversary celebrations.

My uncle asked me if I wanted to go, and with absolutely no hope of getting close to the great man, I went with a small notebook for company.

As it turned out, I made it to the stage and the small crush of people around him. Embarrassed, I mumbled something and thrust the notebook his way.

It was smaller than his palm. But instead of a wisecrack, he slowly took my pen and started writing his name. It took him over a minute. His hands trembled violently, and the letters were grouped together like a Kerala rowing boat. Needless to say, I was only one of many people whose day he made.

After that, I read every significant piece of literature on him, and watched every fight. Many will always wonder how good he might have been if he had not lost three and a half of the best years of his life because of the refusal to serve in Vietnam.

One thing’s for sure – the Ali who ground out victories against Frazier, Foreman and Ken Norton was a far cry from the twinkle-toed, lightning-handed boxer who thoroughly dominated Cleveland Williams and Ernie Terrell. He had lost some of his skills, but the will remained.

My grandfather suffered with Parkinson’s before he passed away. My older nephew, who I love as a first child, shares his birthday, January 17, with The Greatest.

The other nephew was born 32 years to the day after Manila.

His legacy transcends both sport and politics. “At a time when blacks who spoke up about injustice were labelled uppity and often arrested under one pretext or another, Muhammad willingly sacrificed the best years of his career to stand tall and fight for what he believed was right,” said Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the great basketball player, putting things into perspective.

“In doing so, he made all Americans, black and white, stand taller. I may be 7ft 2in but I never felt taller than when standing in his shadow.”

Few sportspersons, leave alone boxers, will ever move out of it.

sports@thenational.ae

Follow us on Twitter @NatSportUAE

Like us on Facebook at facebook.com/TheNationalSport