If 2015 has been a year of surprises, from the unexpected staying power of Donald Trump’s presidential bid to the shock devaluation of China’s renminbi in the summer, it has also been one in which four trends emerged, not all particularly welcome.

One was that this is the year we learnt that international borders are no longer fixed. If there was ever any hope that Crimea would be returned to Ukraine, thus preserving the post-war convention that countries do not invade and then officially annex parts of other sovereign states, it evaporated in 2015.

As the Bulgarian journalist Dimiter Kenarov put it recently: “There is no turning back. Crimea may be a millstone around Russia’s neck, but it is also a crown jewel that it will guard at all costs. The peninsula will leave Moscow’s control only if the Russian Federation itself falls apart.”

Talk of a new Sunni state coming into being after ISIL is defeated suggests that the boundaries of Syria and Iraq are lines in the sand that the international community no longer regards as being sacrosanct.

“I can see a time in the future where Syria is fractured into two or three parts,” was the assessment of lieutenant general Vincent Stewart, head of the US Defence Intelligence Agency in September, to the question the Middle East scholar Juan Cole posed exactly one year ago: “Will Iraq ever exist again?”

More positively, India and Bangladesh simplified their borders by exchanging some of the nearly 200 enclaves, counter-enclaves and even one counter-counter enclave that lay either side of the boundary, ending a confusion that began, according to legend, when two local rajas used the areas as stakes in a game of chess.

Two. This is the year in which mainstream political parties and candidates appear to have lost their dominance in many major democracies. In America, the Trump phenomenon has consigned less radical Republican leaders, including governors Scott Walker, John Kasich and Bobby Jindal, to the margins.

In Europe, the far-left Syriza took power in Greece, reducing the once-mighty socialist party, Pasok, to under 5 per cent in January’s general election.

In other parts of the continent, new parties or longstanding insurgents may not have taken power on their own, but from the National Front in France to the Danish People’s Party they have contributed to a “remaking of the political order”, as Mark Leonard of the European Council on Foreign Relations puts it.

“Centrist parties that have run politics over the last few decades,” he concludes, are “being hollowed out and replaced by parties appealing to the fringes”.

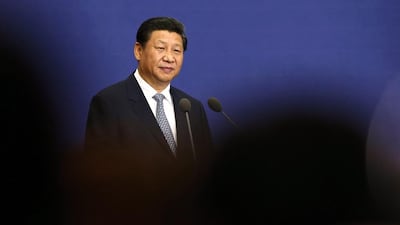

Three. This is the year in which the true extent of China’s new assertiveness has become abundantly clear. New satellite images from the disputed South China Sea have shown land reclamation so extensive it has been nicknamed the “Great Wall of Sand”, and construction far more extensive than previously thought

One set of buildings is as large as the Pentagon, while airstrips with evident military capability are proliferating. Protests from countries with their own claims on the reefs and rocks have been firmly rebuffed, while US criticism has led to tart responses.

In March, the deadline for joining as a founding member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank led to a slap in the face for US hegemony as a string of Washington’s allies, led by Britain, ignored exhortations not to join, and did so to thinly veiled American fury.

And in November, the renminbi was awarded reserve currency status by the IMF, joining an elite club of just four other currencies and underlining China’s position as a global economic power.

Four. It has also been clear this year that the “end of history” and the imminent universal adoption of western liberal democracy once heralded by Francis Fukuyama is as far off as ever.

Indeed, “illiberal democracy” as Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, provocatively puts it, is only strengthening in parts of the world.

Mr Orban cited Russia and Turkey as two countries that were successful without being liberal; and whatever criticisms may be made of them at home and abroad, there can be no denying the popularity of presidents Putin and Erdogan.

The latter won a decisive victory in November’s general election, while a recent poll put the former’s approval ratings at a stratospheric 89.9 per cent.

In the Middle East and beyond, there is equally no denying that the medieval rigidity and cruelty of ISIL unfortunately does appeal to the deluded and the dangerous.

Meanwhile, the prospects for liberal democracy in Afghanistan are so dim that a former coalition general who served there noted correctly last week not only that “we had tolerated the Taliban running Afghanistan for some years as a better alternative to the civil war that preceded it”; but also, that “given the rising threat of ISIL in Afghanistan, the Taliban might be seen as the best local hope of resisting and defeating ISIL expansion there”.

Small comfort to those who cherish education and opportunities for women, to mention one liberty curtailed under the country’s former rulers.

The above may not appear to be a very tempting quartet (although China’s assertiveness strikes me more as the “sleeping giant” awakening to retake its place in the world than anything to be feared). But a cold dose of reality is better than the complacent assumptions and ill-informed idealism that have contributed to those trends in the first place.

If next year decision-makers follow the advice of Jack Welch – “deal with the world as it is, not how you’d like it to be” – there may be a happier summing-up to the end of 2016.

Sholto Byrnes is a senior fellow at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies, Malaysia