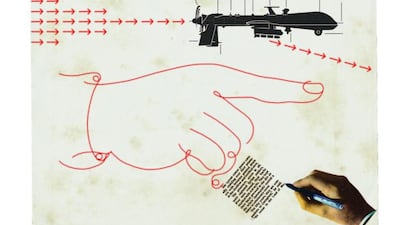

Three beheadings have compelled the US into an action that nearly 200,000 gruesome deaths had failed to precipitate.

Last Monday, the US launched a bombing campaign in Syria putatively aimed at the extremist jihadi group ISIL. Also targeted were some “Al Qaeda-linked” organisations. The strikes killed many members of Jabhat Al Nusra (JAN) and Ahrar Al Sham (AS). Both groups are hardline, but their focus is regional. Neither threatens the US; both fight ISIL.

But for the US, according to one administration official, it is all “a toxic soup of terrorists”.

Syrian dictator Bashar Al Assad concurs. State media quoted him as supporting any international effort to combat “terrorism” in Syria. For weeks, his regime had been volunteering itself as an ally to the US in its “war on terror”, a status that it had enjoyed under George W Bush. Damascus was once a favoured destination for CIA rendition flights.

It is possible it got its wish. The Syrian opposition, which western polemicists habitually describe as “US-backed”, received no warning of the attacks. The US State department said Assad did. The Free Syria Army (FSA) learnt of the attacks from the news.

If JAN and AS have ended up in the same “toxic soup” with their rival ISIL, then it has much to do with poor intelligence and an impoverished media discourse.

While working as a CIA consultant during the 1970s, the wife of the late political scientist Chalmers Johnson asked him why so much of the agency’s analysis was classified. Because, Johnson replied, it would kill its mystique if the public were to learn how banal much of the analysis was.

This was made glaringly obvious when a perusal of the 2002 National Intelligence Estimate revealed that the CIA had relied for its most significant claim – that Iraq had links to Al Qaeda – on an article David Rose wrote for Vanity Fair.

Dick Cheney, then vice-president of the US, made the same claim citing a New Yorker article by Jeffrey Goldberg. Colin Powell, then Secretary of State, on the other hand relied on a confession extracted under torture from an Al Qaeda fighter in an Egyptian prison.

Needless to say, the claims proved false. David Rose had been fed the information by a defector furnished by Ahmed Chalabi’s opposition organisation, the Iraq National Congress; Jeffrey Goldberg was duped by a prisoner held in a Kurdish separatist prison.

(Rose has himself admitted and apologised for the INC story and Goldberg’s story was debunked within months by the Observer’s Jason Burke who spoke to the same prisoner.)

Eager for scoops, both credulously relayed the stories; and eager to furnish serviceable information, the CIA gave them credence. Together they helped trigger one of the most disastrous interventions in recent history.

There is reason to be wary of similar motivations in Syria. CNN has revealed that the claims of a plot against the US, which President Obama believes he has thwarted with his attack on JAN (which the US identifies as the Khorasan Group), might have come from a fighter held in a Syrian regime prison (under torture, no doubt). If there is ready acceptance of such claims, it is because ideologues in journalistic guise have done much to erase such distinctions.

Syria has been a deadly conflict for journalists – 70 have been killed covering the uprising so far. Even veteran war correspondents are steering clear. Into this void have jumped the freelancers and citizen journalists. Some of them have produced invaluable work, but most serve dross.

In the absence of authoritative voices, the few who still visit have gained outsize influence. But since safety is guaranteed only to those who embed with the regime, foreign journalists have become hostages to its information management.

The main tenet of the propaganda campaign – one echoed by its sponsors in Tehran and Moscow – is that the regime is fighting a “war on terror” similar to the one the US is waging.

Central to this strategy is portraying all of Assad’s opponents as Islamist extremists, cut from the same cloth as Osama bin Laden. If the regime is using excessive force, then this is made unavoidable by the implacable character of the foe.

This meme has been faithfully relayed by foreign correspondents who have covered the conflict from regime-controlled areas. The most prominent among these is Patrick Cockburn of The Independent, a veteran of many wars and a winner of many journalism awards. His new book, The Jihadi’s Return, is enjoying considerable success. The book blames the West and its Gulf allies for creating ISIL by supporting the Syrian uprising and fostering instability. The overspill from this, he argues, has also upset the fragile communal balance in Iraq.

Cockburn derides the contradictions of US policy. It is seeking to strengthen the Iraqi government against ISIL, he says, while simultaneously trying to weaken the one in Damascus.

This is senseless, Cockburn argues, since Bashar Al Assad’s forces alone are capable of confronting ISIL. Syria’s “moderate” opposition is a fiction, he says. It shares an extremist ideology with its murderous and Al Qaeda-like vanguard. In arming them, the US might as well be delivering weapons to ISIL.

Cockburn’s penchant for understatement gives his writings an air of objectivity. But a peep below the surface reveals a less wholesome reality. Cockburn attributes his most incendiary claim – that the FSA is in cahoots with ISIL – to an “intelligence officer from a Middle Eastern country neighbouring Syria”. Might this unnamed country be Iraq? After all, if the source itself is unnamed, what need is there to conceal the country? Unless, of course, the country is Iran, a close Assad ally, which nullifies the claim.

But Cockburn’s problems aren’t limited to sourcing. There is also a question of credibility.

In the book, he writes that in early 2014: “I witnessed JAN forces storm a housing complex by advancing through a drainage pipe which came out behind government lines, where they proceeded to kill Alawites and Christians.” However, when one looks at Cockburn’s January 28, 2014 column for The Independent, the story is attributed to “a Syrian soldier, who gave his name as Abu Ali”. In that version, Cockburn wasn’t a witness.

Cockburn eschews the bombastic judgments of his colleague Robert Fisk. Instead he uses references, analogies and elisions to mark the distribution of good and evil.

Superlatives are reserved exclusively for the opposition. They are depicted as “head choppers”, reminiscent of the Nazis. Their crimes are vividly described. To the extent that the regime’s misdeeds receive attention, they are described in general terms, often as preludes to another account of rebel barbarity.

Yet it is accounts such as these that are shaping opinion – and even policy. Syrians, who are already trapped between the regime and ISIL, have also to endure the slings and arrows of hack missionaries with ideological axes to grind. If we demand accountability of our politicians we must also expect higher standards of our opinion makers. Until then, they must stand impeached.

Muhammad Idrees Ahmad is a lecturer in Journalism at the University of Stirling and the author of The Road to Iraq: The Making of a Neoconservative War

Twitter: @im_pulse