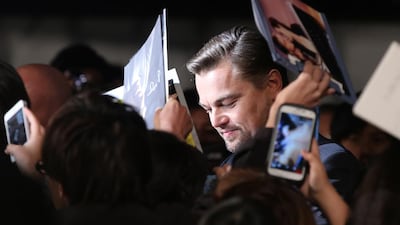

Earlier this week, the idea was floated that the actor Leonardo DiCaprio might star in a forthcoming film based on the life of Jalal Al-Din Rumi, the 13th century mystic, poet and scholar. Much controversy ensued, with many pointing out that Rumi could never be mistaken for a white European as he was from what is now Iran. It’s unclear if DiCaprio is being seriously considered for the role or even if the project is likely to be produced – but it did bring up the issues of “whitewashing” Islamic mysticism, or Sufism, if not Rumi himself.

It wouldn’t be the first time that a Hollywood film took people of colour from Asia or Africa and presented them as white. In most western films about ancient Egypt, for example, Egyptians are portrayed as white Europeans. Films depicting Jesus of Nazareth regularly show him in the same fashion, even though, as a Palestinian Jew he would have been far more similar to contemporary Palestinians in skin tone and features. But the issue of Sufism in particular is striking – because it has received its own specific type of misrepresentation.

When Muhammad Ali passed away this month, a number of obituaries noted that he had “embraced Sufi Islam”, with the implication that Ali had moved on from the more normative Sunni Islam he had integrated into following his departure from the heterodox “Nation of Islam”.

A number of books have already established Rumi as somehow being a part of Sufi Islam, which appears to be distinct and separate from a more regular and orthodox Sunnism. In this regard, Ali and Rumi, it seems, are somewhat different from regular Muslims.

Of course, Ali and Rumi are different but they were still Sunnis, and rather extraordinary human beings.

Imam Zaid Shakir, the imam who presided over funeral prayers for the boxing legend this week, is a Sunni teacher in the United States who also upholds Sufism as an integral part of Sunnism. When one looks at the life of Rumi himself, one finds not a new age transcendent preacher, but a Sunni judge of Islamic law, while at the same time being one of the most recognised Sufi saints of Muslim history.

The same might be said of most Sufi figures in Muslim history past or present.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, for example, the Spanish mystic, Ibn Arabi (1165-1240), has often been cited as a Sufi who transcended Islam, and regarded all religions as essentially the same. Yet, Ibn Arabi was a highly orthodox Sunni Muslim, who also held strictly to a traditional school of canon jurisprudence, while also writing deeply moving spiritual poetry.

Sufism may have inspired a lot of new age spirituality in the last 60 years in the West – but its history is very much integral to standard expressions of Islam in its classical forms, both Sunni and Shia.

But public assessments of Sufism have often missed the mark – and not simply in the West. Often times, Sufism is described in different quarters as the pacifist form of Islam – a form that will be the antidote to ISIL.

In many ways, Sufism is just that, in that it is deeply rooted in mainstream Islamic expressions, while extremists have distanced themselves from the mainstream precisely because it isn’t radical enough for them.

Yet, to mistake Sufism as somehow akin to pacifism might make for uncomfortable readings of history. In the Free Syrian Army today, there are many who describe themselves as Sufis who are nonetheless fighting what they deem to be a just cause.

During the Italian fascist occupation of Libya, the Libyan resistance movement was led by a Libyan Sufi of the Sanusi order, Omar Al Mukhtar. The most renowned Sufis of their era, such as Abul Hasan Al Shadhili, fought against the Crusader forces of King Louis when his armies invaded Egypt at Mansurah in the 13th century. The examples are plentiful, in other words. That shouldn’t be surprising – because at least historically Sufism has never been uniquely pacifist, even while it has been the repository of the deeper spiritual sciences of Islam. But when Sufis fought, it wasn’t an indulging in wanton violence – they always saw them as “just wars”.

It’s unclear what might become of that proposed film about Rumi, and who might eventually portray him. One hopes that whatever does come of it, that it will portray the man and his beliefs accurately, rather than whitewash him – whether in his race or in his thoughts.

Dr HA Hellyer is an associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute in London and a non-resident senior fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East in Washington, DC

On Twitter: @hahellyer