Last week saw one of the greatest political comebacks in American history, not only for Joe Biden, or even the Democratic Party, but for reason, seriousness and sanity.

Two weeks ago, Mr Biden, a former American vice president, was given up for dead. He suffered massive defeats in primaries – as party elections in the US are known – in Iowa, New Hampshire and Nevada. Now he is not only the likely Democratic nominee for president, but it seems increasingly realistic he could go on to beat incumbent President Donald Trump in November.

Mr Biden spent much less than many of his competitors. He had also barely set foot in several of the states he won. What happened was the sudden coalescing of the Democratic Party's moderate centre around a plausible and time-tested leader, no matter how elderly and uninspiring, as the best corrective to both Mr Trump and the self-described "democratic socialist" Bernie Sanders, who has yet to even formally join the party for which he is running.

The turning point was the South Carolina primary on February 29, which delivered a landslide win to Mr Biden, mainly due to the backing of Jim Clyburn, an African-American congressman and his constituents in South Carolina.

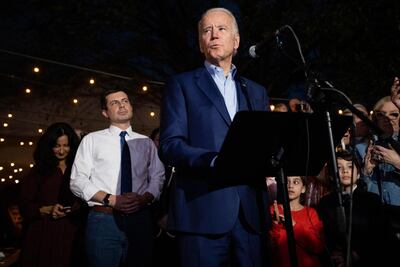

Two other centrist Democratic candidates, Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, withdrew from the race and endorsed Biden, as did many other leaders in the party.

Until then, the Democrats seemed on course to repeat the Republican debacle of a hostile takeover by Mr Trump in 2016. After the Iowa and Nevada results, the party seemed to be collapsing in the face of a concerted insurgency from a radical but unified minority of about 25 per cent that supported Mr Sanders. It now appears, however, that the party is more resilient than many thought.

Mr Biden emerged as the main competitor to Mr Sanders after South Carolina. Mainstream Democrats suddenly united, handing Mr Biden a stunning set of victories on March 3, a day known in the jargon of American politics as “Super Tuesday.”

Still, Mr Sanders and another senator, Elizabeth Warren, have pushed the Democratic conversation significantly to the left. To unite their party and effectively challenge Mr Trump, centrist Democrats must now develop serious policies to tackle the pressing issues those two senators ran on, such as income inequality, health and child care, immigration and student debt.

White nationalists and religious fanatics among Mr Trump's base are clearly unreachable. However, millions of Trump voters are primarily motivated by economic and social – not racial or cultural – grievances. They are angry at feeling left behind in an era of unprecedented – and frightening –technological, social and economic transformation.

Mr Trump, Mr Sanders and other left and right populists around the world exploit this fear and anger, promising to reorient society in the favor of their respective bases.

It is a potent message, but Mr Sanders now seems to have no real path to the nomination. Primaries in his strongest areas, including California, are over. Mr Biden has momentum, the support of numerous trusted and popular figures and strong poll numbers.

Of course, Mr Sanders could make a comeback, particularly since Mr Biden did. Mr Trump's win in 2016, moreover, is evidence that the improbable is still very possible. But in Mr Sanders's case, it seems increasingly unlikely.

If, as seems more plausible, neither has a majority of pledged delegates going into the convention this summer, Democratic leaders and elected officials will choose between a long-time stalwart and someone who never even agreed to join their party at all. The outcome is obvious.

Meanwhile, Mr Trump looks increasingly vulnerable.

The spread of coronavirus has cast his administration as woefully unprepared, particularly when it comes to testing.

The President's wild statements – such as declarations that criticism of his handling of the virus is a "hoax”, or his blaming slow testing on his predecessor, Barack Obama, and many other comments that significantly downplay the crisis or cast it in political, and even personal terms – may well haunt him. A lack of testing available throughout the US, in particular, is a potentially devastating scandal.

Once the personal, social and economic impact of the crisis is truly felt by ordinary Americans in their daily lives, Mr Trump, as president, will – fairly or not – inevitably be held responsible. As with the economy, no one else, including the vice president or a predecessor, can be effectively blamed when a calamity ensues.

Americans are already watching not only their government failing to meet the challenge, but also serious and once-respected officials and agencies publicly embarrass themselves to serve Mr Trump's personal messaging and self-regard.

Mr Trump has also blundered by saying he intends to cut popular government services including public pension payments and health care. In 2016, he was elected by loudly insisting he was the only Republican, and even the only candidate, who would protect such programmes.

Biden attack adverts for the November election on the economy, the virus and the future of these programmes may write and produce themselves.

Mr Sanders has a sizeable and devoted coalition, and the 2016 election shows that anything can still happen. But many Democrats have rejected him because they do not feel part of any "democratic socialist" coalition, and because they sense that Mr Trump's 2016 winning coalition is larger.

Their more serious bet, though, is that Mr Biden’s emerging coalition, very similar to that of Mr Obama, is significantly larger than that of Mr Trump.

Mr Biden's astonishing and unprecedented political resurrection demonstrates the folly of presuming anything and the importance of remembering that the unexpected can happen.

Given the supersonic speed of Washington politics in the Trump era, November seems an aeon away.

But if the Democrats continue to refuse any repetition of the Republican Party’s shift to the radical right after Mr Obama's election, and its subsequent inability to defeat a hostile takeover by Mr Trump, they will be throwing moderate American politics a crucial lifeline.

Democrats, from the grassroots to party leaders, appear determined to nominate Mr Biden. They would not only be rejecting their own self-defeating maximalism. They would offer millions of other Americans, including Republicans and former Trump voters, the chance to elect a reasonable, competent and serious government.

That would be powerfully appealing. Don't bet against it.

Hussein Ibish is a senior resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington