Last week, a much-anticipated US intelligence report on UFOs raised the age-old fascination humans have with the idea that one day, for better or worse, we might come into contact with other intelligent lifeforms. The scenario is a fascinating one precisely because its implications would be so great and so strange. Another recent story, however, has revealed that there is in fact precedent for humans living side by side with different intelligent beings. And the origin of this remarkable episode was not outer space, but the Middle East.

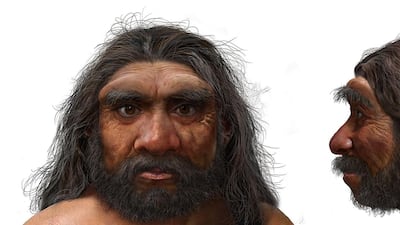

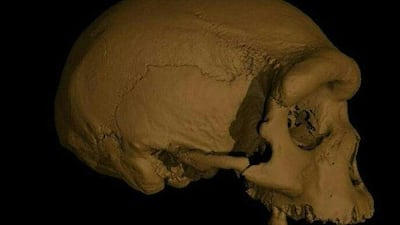

On Friday, an article in the journal Science detailed a discovery made by Israeli researchers of bone fragments belonging to a body from a group that has now been named the Nesher Ramla Homo species, early humans whose existence was previously unknown. The most fascinating aspect of the discovery is that it would mean our ancestors lived alongside other hominid species for thousands of generations, likely interacting, sharing knowledge on hunting and even interbreeding. The discovery is being hailed as a groundbreaking piece in the puzzle of human development.

This discovery means a new era in pre-historic archaeology will concentrate on the Middle East, long overdue in an academic field that has disproportionately focused on the western world. It also adds to the story of our region as one of the most consequential melting pots and centres of human development on the planet, although many will need little reminding. The Middle East is no stranger to archaeological breakthroughs. Only a few months ago, a 3,000-year-old city was unearthed by researchers in Egypt, a moment that was described by some Egyptologists as the most important find since the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The news will also focus the minds of genealogists on the importance of the Middle East to their field. Researchers are already claiming that last week's discovery might settle a decades-old debate on how a later branch of early human species, the Neanderthals, emerged in Europe. Nesher Ramla Homo could well turn out to be their early ancestors, and the reason Neanderthals, whose origins have so far never been pinned down, were genetically so similar to Homo Sapiens.

This will fuel a growing interest in the region on its genetic makeup. Last month, The National wrote about the work of the Emirati Genome Project, launched last year to understand more about genetic profiles in the Gulf, knowledge that could help scientists, among other more theoretical lessons, uncover particular medical vulnerabilities of those from the region.

Most symbolically, these simple bone fragments are enough to remind the world of the Middle East's contribution to humanity. In a part of the world that is so often the focus of media attention because of political issues, the investment in disciplines such as archaeology can show the world that the region is more than just its contemporary difficulties.

Ancient Mesopotamia, an area spanning modern-day Iraq, is known famously as the cradle of civilisation. For the wider Middle East, evidence is mounting that this legacy stretches back even further, now into pre-history.