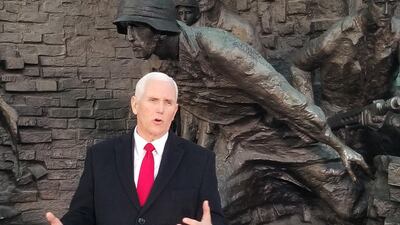

European leaders are reeling following the verbal assault on their Iran policy by Mike Pence, the US vice president, in Warsaw last week.

Within the constraints of the transatlantic alliance, it is not sustainable for the US, as the leading force, to accuse its partners of undermining one of its prime foreign policy missions.

That is what Mr Pence has done and his admonition cannot be erased easily.

This is a crisis that has been brewing for months. Europe has not been listening to America, or, at least, not properly examining the implications of Washington’s withdrawal last year from the 2015 nuclear agreement with Iran.

America’s relationship with Iran has been toxic ever since the 444-day siege of the US embassy in Tehran in 1979. Decades later, the fallout stands as a grim chapter in ever-worsening relations.

Now it has become an open wound in the transatlantic relationship, with dire implications.

At the Munich Security Conference this week, which acts as the Davos of the securocrats, the state of the alliance is a source of much gloom.

Federica Mogherini, the EU's foreign policy representative, spoke with some frustration about the extent of European efforts to salvage the nuclear accord. She pointed out the pressure that had been brought to bear on her and other leaders. With a fixed smile, she asked if the accord would still exist without Europe.

Kori Schake, the deputy director of the International Institute of Strategic Studies (IISS), said the Europeans had done almost all “heavy lifting” on the fightback against the US withdrawal, pointing out China and Russia were also party to the deal. The tailgating by those rival powers has left Europe dangerously exposed.

Europe's rulers have a bureaucratic mindset and view the issue through a policy prism. The Trump administration and its supporters have a far more visceral perspective.

As senator Lindsey Graham, an ally of the US president, told the Munich meeting: "You don't provide funds for someone who wants to stab you". The equation in their minds is that the accord gives Iran money that is directed into aggression.

Until now, there has been a desire by the Europeans to offset US accusations. In this it has been encouraged by a US invitation to come up with specific action against Iran.

This approach only works up to a point. It ultimately results in a failure to see the wood from the trees.

Arrests followed when Iran conducted an assassination plot through its embassy in Vienna. But there was no serious effort to censure Tehran by shutting down its diplomatic presence in the way Russia’s was degraded after the Salisbury poisonings targeting a double agent in England.

Europeans subscribed to the UN findings that Houthis had fired Iranian-supplied missiles at Saudi Arabia. Yet Europe’s foreign ministries fought against suggestions the Houthis are proxies for Iran as part of Tehran's policy of destabilising the Middle East.

So while Brian Hook, the US special representative on Iran, welcomed multiple European measures against Iran over the last eight months, he also warned against the tendency to normalise aggression. "Iran has been practicing terrorism in Europe for 40 years. We are therefore happy that Europe is reacting to those actions," he said. "If you see the challenges that this region faces, Iran is usually in the centre of it all. We have not heard any government here defending the Iranian regime and its policies. We have differences in tactics and style [from the Europeans] but no one is defending this regime."

The divide comes as Europe is struggling to define its contribution to the US-led security umbrella.

Since the presidency of Barack Obama, Washington has insisted that European countries spend more on defence.

New estimates show that if European countries were to meet the two per cent of GDP target agreed for Nato countries at a summit in Wales in 2012, spending would instantly rise by $102 billion. To close that spending gap, the countries below the line would have to produce a massive 38 per cent hike in military outlay.

It is not just that spending is too low. Europeans are very bad at getting value for money. Britain spends the required two per cent, which means its expenditure is about level with Russia.

Given the recent gains in Russian positions in several countries, it's not hard to argue the Kremlin gets more bang for its buck.

Europe is in a quandary. Nicholas Burns, the former US ambassador to Nato, argued last week that he was wrong to fight European efforts to achieve defence integration 15 years ago.

A report from Harvard’s Belfer Centre, which he presented, argued that the pace of change in military spending was about to undergo revolutionary challenges as a result of technology developments.

America is right to put Europe under extreme and sometimes undiplomatic pressure over Iran. The Tehran regime’s statecraft faces both ways, allowing it to reap the benefits of negotiations while targeting its neighbours and enemies.

In an era of great power rivalry, America would be unwise to push its alliance with Europe to the brink. The challenges, both known and foreseen, are fast evolving and too much is at stake.