As US President Donald Trump flew into Ohio and Texas this week, protesters lined the streets outside the venues where he was meeting survivors and families of victims of two shootings that claimed 31 lives in less than 24 hours.

Many held placards condemning his rhetoric for fuelling the hate behind the attacks and his failure to introduce better gun controls. One sign in Dayton simply read: “You are why.”

These demonstrators have been joined by a phalanx of politicians and public officials in a chorus growing ever louder over these twin evils in American society. For while the US has long wrangled over gun ownership laws, the shootings have brought into sharp focus the nation’s failure to tackle white supremacy.

The 21-year-old white male accused of killing 22 people in a Walmart supermarket in El Paso on the Mexican border allegedly wrote a manifesto filled with white supremacist language and hate aimed at the Hispanic community. Meanwhile the alleged perpetrator of the nine fatalities in Dayton, Ohio, a 24-year-old white male, was reportedly obsessed with violent ideologies.

Yet even as Mr Trump called for the country to "condemn racism, bigotry and white supremacy" in the wake of the attacks, he followed that by saying: "Mental illness and hatred pull the trigger. Not the gun", drawing condemnation from mental health experts and accusations that he was making excuses for violent criminal behaviour, without any psychiatric evidence to back them up. And instead of supporting gun control measures proposed by Congress, he has instead suggested reforms of mental health laws and blamed video games for glorifying violence.

Mass shootings threaten to turn the country into a 21st century powder keg. In the past few months, the nation has been shaken to its core by gun massacres from Sebring, Florida, to Gilroy, California, bringing the total number of mass shootings in the country to more than one per day. The last time mass shootings reached such a frequency was 2016, which saw 382 incidents.

Gun ownership is enshrined in the Constitution, a legacy rooted in the very foundations of the US.

Gun violence dates back to the Civil War; one of the founding fathers of the nation, Alexander Hamilton, was himself killed in a duel to the death with his political rival Aaron Burr in 1804. Texas law today still permits the open carrying of a handgun and allows two individuals to go toe-to-toe and settle their differences in a street fight. Since the violence and exploitation of the natives who first inhabited American soil, one might question whether our motto should actually be “in guns we trust”.

As the nation and the world watch the growing number of mass shootings with alarm, Americans are looking to leadership for answers on how to keep our country safe. Yet those answers are in short supply.

___________

Explained: US mass shootings

___________

The president has called on government agencies to work together and identify individuals who might commit violent acts. He has also called for legislation allowing law enforcement to take weapons from individuals thought to be a threat to themselves or others. Some might argue that should start with law enforcement officers themselves disarming.

Most would agree that anyone with a mental illness or a record of hatred, racism or bigotry should not be in possession of a firearm. However, as the shooting of unarmed black men such as Oscar Grant, Stephon Clark, Botham Jean, Jamar Clark and Emantic Bradford Junior, among others, shows, many law enforcement officers are themselves guilty of racial bias – yet the criminal justice system leans towards protecting them rather than their victims, even in cases of extreme violations with video evidence.

Giving more authority to police officers would only serve to intensify those elements of racism and corruption among the ranks of officials and further empower the white nationalist agenda.

And as the statistics show, those who are feared most are rarely those who pose the greatest threat. Last month, FBI director Christopher Wray revealed the majority of investigations into domestic terrorism – by homegrown, radicalised extremists – involved some form of white supremacy. Earlier this year, FBI officials said they were looking into about 850 cases of domestic terrorism posing a “serious and persistent threat”.

Yet when these cases result in an arrest and criminal trial, they are usually charged with non-terrorist offences. Of the 60 groups the US deems terrorist organisations, most are Islamist and based overseas.

As Michael McGarrity told the House Committee on Homeland Security in May: “A white supremacist organisation is an ideology, a belief – but they’re not designated as a terrorist organisation.” This, then, is part of the problem: while the greatest threat to Americans is from white supremacy, it is rarely, if ever, labelled terrorism and instead spoken of almost empathetically as mental illness. The language used in describing such attacks and their perpetrators distorts their gravitas. As Democratic presidential candidate Cory Booker tweeted: “White supremacy is not a mental illness, and guns are a tool that white supremacists use to fulfill their hate.”

To be a white American is to be privileged throughout the world. Some believe the rise in white nationalism is related to census predictions that white people will be a minority in the US by 2045. In the early days of America, lynchings were a way of social and racial control, terrorising black people into submission. Mass shootings have become their modern-day equivalent, a violent beating of the chest to gain attention of all the animals in the jungle and to inform the world of who holds the power.

The Second Amendment to the Constitution, often cited by gun ownership advocates, reads: “A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.” Its premise seems to be rooted in fear and its interpretation begs the question: what defines a well-regulated militia and who determines which people can form one?

Absent is the voice of the National Rifle Association, which during the 1990s used its influence over NRA member and Arkansas representative Jay Dickey to insert an amendment into the federal spending bill that has effectively prevented the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention from funding any research on gun violence. The NRA and its allies in the gun lobby maintain a firm grip on the Republican party, which made the last attempt by the Clinton administration to limit the spread of gun violence a difficult task.

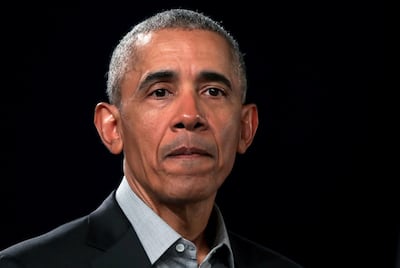

Then president Bill Clinton was finally able to introduce the Federal Assault Weapons Ban but it was only in effect for 10 years. The temporary law banned the manufacture, sale and possession of military-style assault weapons like the AR-15. Barack Obama, too, faced huge opposition as he unsuccessfully tried to strengthen gun control laws while in office and said his failure to do so was the “greatest frustration” of his presidency.

The discussion of guns and violence in America needs to include the corruption and misuse of authority by law enforcement as well as their reluctance to treat white murderers as terrorists. Terrorism has become a term targeting the “other” while white American mass murderers are rarely, if ever, described as terrorists. There is, instead, a soft-pedalling of language and craven attempts to humanise the perpetrator.

That was blatantly evident when, in June 2015, nine churchgoers were gunned down in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. White supremacist killer Dylann Roof was arrested in Shelby, North Carolina, but before being charged with murder, police found it necessary to treat him to food from a nearby Burger King. Unlike the San Bernardino shooting of 2015, or the Orlando nightclub shooting in 2016, he was not charged for an act of terrorism. Nor was the perpetrator of the attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, who killed 11 people.

As congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said: “Attacks committed by Muslim Americans [are] almost automatically labelled as domestic terrorist incidents yet white supremacist shooting, after shooting, after shooting, is not. I can’t help but come to the conclusion that what is labelled as terrorism almost exclusively comes down to identity, and it seems white men invoking white supremacy and engaging in mass shootings are immune from being labelled domestic terrorists.”

When non-whites commit the same crimes, their entire communities are held culpable, sparking calls for tougher laws and more fear. I hold one passport but it is connected to two Americas. The first America is responsible for building the second; and the second America has been taught to fear those who built the first. Yet I love them both, despite the serious challenges in navigating my life between the two.

Presidential candidate Pete Buttigieg recently challenged Americans to think critically and to acknowledge that “this is terrorism and it needs to be named as such”. Mr Obama also urged Americans to reject language from any leaders that feeds hatred or normalises racism.

What is most tragic about the events that have been unfolding over the last few years is that it appears the right of a people to bear arms is more important than the right to live in peace. We might not be able to eliminate hatred and racism completely from society but we can show good moral character, strong leadership and treat all people with the same level of honour, dignity and respect that we expect for ourselves.

Dr Adam Jeffers is an assistant professor at Zayed University, with a focus on education and incarceration. He was a keynote speaker at the 80th anniversary of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People