US President Donald Trump did his successor Joe Biden a favour last week when he sanctioned Turkey under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA).

The new sanctions, in response to Turkey’s purchase of Russian-made S-400 missile defence systems, were required under US law, and thus all but inevitable. The US State Department has barred American dealings with Turkey’s military procurement body, its chief and three top officials.

In the context of the broader Turkish economy, this amounts to little more than a slap on the wrist. But depending how long they remain in place, the sanctions could do real damage to Turkey’s defence industry, which relies on US imports. That industry has matured a great deal under the Justice and Development Party (AKP), from a $5 billion budget in 2002 to $60bn today, while producing some of the world’s most advanced drones.

Of course, Turkish defence industry leaders will not have forgotten that it was a previous punishment from Washington – an American arms embargo from 1975-78, in response to Turkey’s invasion of Cyprus – that helped spur their sector’s development in the first place. They may see these latest sanctions as another hurdle to overcome, rather than an unprecedented assault.

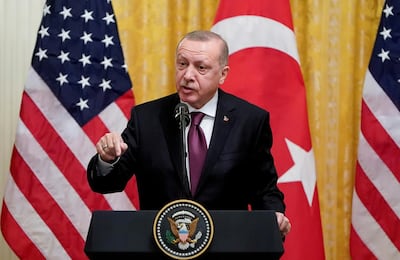

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, unsurprisingly, has decried the sanctions as a blatant attack on a Nato ally. But it is undeniably better for Mr Biden that Mr Trump levied them now, clearing the way for the next administration to take office without being on a direct collision course with Turkey.

Of course, the two sides are not about to change their stripes. Mr Biden's White House is most likely to call for greater respect for human rights, international law and the continued integrity of defence alliances like Nato, while Mr Erdogan's Turkey will remain dogged and challenge the western system at nearly every turn.

US analysts and some officials will, in the days ahead, denounce Mr Erdogan's authoritarianism and probably call for Turkey to be removed from Nato. Turkish analysts will talk of kicking the US and its nuclear weapons out of Incirlik airbase, as Mr Erdogan continues to push the envelope. The Turkish drillship Oruc Reis, which has been accused of aggressive forays into Greek waters, is already back at sea after a brief return to port under the threat of EU sanctions. Ankara is now calling for Greek islands to be demilitarised.

This is precisely why US sanctions will have little longer-term impact. The US-Turkey relationship is nowadays defined largely by disagreements. These include maritime boundaries in the Eastern Mediterranean, the extradition of Turkish dissident cleric Fethullah Gulen, the US alliance with Syrian Kurds and the rule of law. The threats and disputes have become almost mechanical, habitual.

As with a bickering elderly couple, nobody fears they will divorce. Turkey is too crucial to Nato’s defence strategy, and it needs the US all the more in the face of regional isolation. It also needs the EU as its economy faces growing hardship.

Key to Mr Biden’s success with respect to Turkey will be his ability to work with European leaders to apply greater pressure on Ankara. That groundwork has already been laid. The US sanctions came a few days after the EU concluded its summit with an agreement to levy sanctions on Turkish individuals and entities linked to Eastern Mediterranean drilling. EU leaders said they would seek to co-ordinate with the White House before deciding on harsher sanctions, such as an arms embargo, at their next summit in March.

That gathering, which will come two months after Mr Biden’s January 20 inauguration, may be a bellwether for Turkey-West relations. If Mr Biden and Mr Erdogan have by then agreed on a plan to lift CAATSA sanctions, the EU may once again revert to a softer approach on Turkey. If Mr Erdogan remains uncompromising, things could take a darker turn.

Despite Mr Trump's stated affinity for Mr Erdogan, some analysts have argued that it was the US President's problematic diplomacy that led to these sanctions in the first place. Throughout 2018 and into 2019, Trump defended Turkey's decision to buy the S-400s, laying the blame on the Obama administration and vowing never to levy sanctions. Now that he has done precisely that, Mr Erdogan likely feels betrayed.

But Mr Trump is now on his way out, and the relatively mild sanctions from both the US and EU represent the “Goldilocks approach”: if the punishments had been harsher, the Turkish economy might be imperilled and Mr Erdogan more willing to lash out; if no sanctions had been levied, Mr Erdogan would feel free to do as he pleases on the high seas and beyond.

This makes for a strong starting point for Mr Biden. The warning shots have been fired and the new administration has an opportunity to take a clear diplomatic stand. Assuming Ankara will want to avoid total degradation of its western alliances, the relationship has a solid chance of starting with compromise, rather than confrontation. Mr Erdogan has already begun to talk of major economic and judicial reforms and has talked up how Mr Biden, in his role as vice president under the previous US administration, visited him at his home.

However the looming Biden-Erdogan talks play out, the battered US-Turkey alliance will stagger on. It’s less than ideal. One would sooner have Nato’s two largest militaries on friendlier terms. But at this point, strained relations is the best these two can do.

David Lepeska is a Turkish and Eastern Mediterranean affairs columnist for The National