The dilemma of how to make reparations to descendants of African slaves in America has been a thorn in the country’s side since the abolition of slavery in 1865. When Union troops of the North defeated the Confederacy of the South in the bloodiest battle ever fought on US soil, it was about economic interests, cultural values and the power of federal government, not ending the business and institution of slavery. In the Americas, slavery involved the complete separation of a people from their land, language and culture. These are atrocities difficult to make amends for.

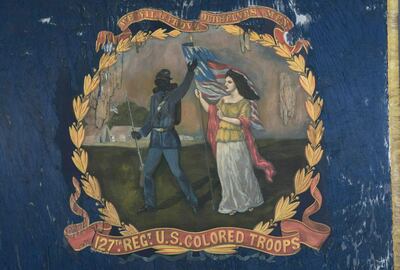

The phrase “40 acres and a mule” formed part of the federal government’s promise to redistribute land seized from white owners to newly freed slaves after the Civil War. In the aftermath of the war, it came to symbolise the rights of African Americans and the government’s broken pledge to compensate them for the crimes of slavery. The order was issued by general William Sherman and approved by then president Abraham Lincoln, who had declared the Emancipation Proclamation two years earlier, granting newly freed slaves the right to compensation for unpaid labour and protection from the military. When Andrew Johnson succeeded him as president after his assassination, however, he quickly vetoed the legislation and returned confiscated land to white southern owners in return for an oath of loyalty. Forty acres and a mule have come to epitomise America’s “unfinished revolution”.

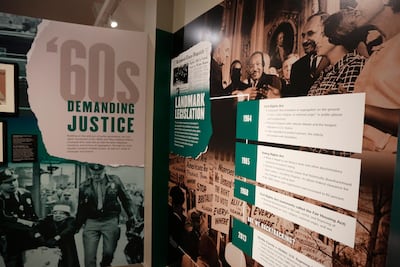

The Juneteenth celebration, commemorating the announcement of the abolition of slavery on June 19, 1865, was marked this year with a long overdue House judiciary committee hearing regarding legislation for reparations. It was overshadowed, however, the day before when Kentucky state senator and Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell told reporters: "I don’t think reparations for something that happened 150 years ago, for whom none of us currently living are responsible, [are] a good idea.” Adding insult to injury, Mr McConnell went on to say: “We've tried to deal with our original sin of slavery by fighting a civil war, passing landmark civil rights legislation. We elected an African American president.” It showed a flagrant misunderstanding of what reparations would mean for the country and, indeed, the rest of the world. If slavery is America’s “original sin”, then surely the country should repent and atone by apologising and making reparations?

The sort of thinking exhibited by Mr McConnell is what many black Americans experience when forced to seek relief for a wrong committed against them, from the very person who committed the wrong. It is like the hen appealing to the fox for fair treatment. It is unclear to what extent the senator has witnessed the effects of slavery but he and many others have undoubtedly benefited from the institutions created by its brutality.

But his comments, however crass and insensitive, do raise an uncomfortable question: why was the issue of slavery and reparations overlooked by the Obama administration? Former president Barack Obama might have done more for race relations in America than any other leader but when he was recently asked about reparations in an interview with the writer Ta-Nehisi Coates for The Atlantic, he was cautious in his response: "I have much more confidence in my ability, or any president or any leader's ability, to mobilise the American people around a multi-year, multibillion-dollar investment to help every child in poverty in this country, than I am in being able to mobilise the country around providing a benefit specific to African Americans as a consequence of slavery."

His statement seems to back the theory that as America’s first black president, Mr Obama was so conscious of how he might be perceived that he disassociated himself from the inflammatory pastor of his church, Jeremiah Wright, and even from the struggles of his own people, so as not to compromise his presidency. Some even claim that the rise of the alt-right and the overt racism found in America today is a direct backlash against his leadership.

Coates eloquently dismantled Mr McConnell’s comments in his heartfelt testimony to the House committee, describing reparations as “a dilemma of inheritance”. Typical of American politics, he shared the stage with the young black writer Coleman Hughes, a critic of reparations, who argued that “our desire to fix the past is compromising America’s opportunity to focus on the present”. His use of the word “our” is questionable and his divisive ideology can be traced back to the days of slavery. There was always a threat of a slave disagreeing or disapproving of the actions of another slave, even going so far as to inform his “master” of plans for a revolt and in some cases, acting on behalf of the slave master.

The Underground Railroad network of escape routes and safe houses remained a closely kept secret, even among slaves, because of the threat of being exposed by too wide a network. The separation of families and preferential treatment for black people with lighter skin and those who worked inside the house were all tools used to divide a people. Slave masters would often use the slave to expose, dishonour and even beat another slave for entertaining thoughts of escaping. These and so many other issues will likely never be repaired.

Perhaps Mr McConnell and Hughes could take a page from Coates's book to realise America's future greatly depends on her ability to reconcile her shameful past. As Coates wrote in his 2014 essay The Case for Reparations: "Here we find the roots of American wealth and democracy – in the for-profit destruction of the most important asset available to any people, the family. The destruction was not incidental to America's rise; it facilitated that rise. By erecting a slave society, America created the economic foundation for its great experiment in democracy."

The suggestions for reparations have been wide-ranging. California senator Kamala Harris has proposed the Lift Act, a bill that would provide a universal tax credit of up to $500 a month to families with an annual income under $100,000. Ms Harris argues the policy would help lift 60 per cent of black families across the nation out of poverty but on the face of it, there seems to be little effort to help black families needing immediate assistance. US representative for Texas Sheila Jackson Lee, meanwhile, suggests establishing a commission to investigate reparation proposals further.

As the descendant of slaves on both sides of my family, I would be directly impacted by its findings. My great-grandfather was William Pascal Russell, a slave who indentured himself to his master in 1863 to earn enough money to purchase land after 12 years of servitude. He bought 58 acres in the Smith Creek township in North Carolina for $750 and helped build St Luke’s Episcopal Church, the first black church of its kind. He went on to establish two schools in an area called Russell Union and some of my immediate family members have returned there in search of a more peaceful existence.

Born in Queens, New York, I grew up in southern California in an area that began as middle class but slowly took on the characteristics of urban life. I have always felt like a member of a group that society either despised, disrespected or simply did not understand. However, my mother instilled certain values in me that have remained a model for how I see the world. What she didn’t prepare me for was what to expect from the world because of the colour of my skin or the legacy of my ancestors. Today, out of habit, I consciously think of how I will be perceived as a black American.

US history is filled with horrific events that prevented the accumulation of black wealth. We hear the stories of the racially motivated Rosewood massacre in Florida in 1923, the mob lynchings in Tulsa, Oklahoma, targeting the wealthy district known as Black Wall Street, and we think how difficult it must have been living in those times. The concept of reparations is not new, nor is it a black and white issue; however, the wealth gap between black and white Americans has remained unchanged in the last century.

I support reparations, although it is ironic that it would present itself in the current political climate. As Americans, we are famous for saying sorry, apologising at the drop of a hat because it is good politics. It does not mean we accept responsibility or even feel guilty, making the word “sorry” ambiguous. It might signify condolence without remorse or it might mean we are sincere, repentant and regretful. Sorry is not the hardest thing to say but knowing what it means is priceless. Former president Bill Clinton issued a formal apology for the deeply unethical 40-year Tuskegee medical experiment on African American men and apologised to Africa twice for slavery, but what does that really mean? Mother wisdom has taught me to exercise caution with the one who is forced to give an apology.

The enslavement of Africans by the people and nations of western Europe created the economic engine that fuelled capitalism in the Americas. Many of the major businesses that currently thrive in the West, founded by western European and American merchants, benefited directly from slavery. Aetna and JP Morgan Chase, to name just a few, have publicly admitted their corporations’ role in slavery. The psychological, emotional, economic and social effects of slavery still ripple through African American societies, affecting families on the continent and in the diaspora. Sincere dialogue on reparations brings them dignity and will help heal a divided nation. It is only when all black people in America are treated with equal respect that the ghosts of the past can finally be laid to rest.

Dr Adam Jeffers is an assistant professor at Zayed University, with a focus on education and incarceration. He was a keynote speaker at the 80th anniversary of the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People