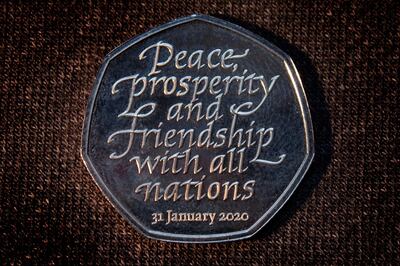

Britain’s future ambitions after it finally completes the tortuous process of ending its membership of the European Union on Friday can best be summed up by the inscription on the 50 pence coin that has been specially minted for the occasion: “Peace, prosperity and friendship with all nations.”

This bold statement, which has the blessing of Prime Minister Boris Johnson, neatly sums up the desire to heal the bitter divisions that have arisen both in the UK and Europe during the three-and-a-half years since the British people first took the historic decision to end their country's 40-odd-year membership of the EU.

When Britain first joined what was then the European Economic Community on January 1, 1973, the six-nation bloc was little more than a trade association that sought to boost the economic strength of its members through easing trade restrictions.

Today the EU, following Britain’s departure, is grown into an organisation formed of 27 nations comprising 450 million people whose ultimate objectives lie well beyond the narrow confines of trading arrangements. The EU’s ultimate goal is to create a federal European superstate based on the model of the United States, with member states subscribing to a common purpose in key areas, such as economic development, foreign policy and security.

Indeed, it was the EU’s insistence on pursuing ever closer political and economic union that ultimately resulted in Britain’s departure.

Looking back over the past four decades of Britain’s EU membership, London’s commitment to the European project had always been half-hearted, to say the least. For example, successive governments, both Conservative and Labour, resisted calls to ditch the pound sterling in favour of joining the EU’s single currency, the euro, the most visible symbol of the EU’s quest for ever-closer integration.

And Britain stubbornly refused to join a range of other EU-led initiatives, such as the Schengen Agreement, which banished internal border checks between EU member states.

The ability of EU workers to move freely within the union, especially after the creation of the single market in 1993, turned out to be a key factor in Britain’s decision to leave the EU, as it resulted in Britain being flooded by hundreds of thousands of workers from poorer countries in eastern Europe – such as Poland, Romania and Hungary – and undercutting the wages of British workers.

Now, with Britain finally making its exit from the EU, the arguments over the whys and wherefores of the decision to leave are a subject for future historians to discuss. For when Britain wakes up to its new dawn of post-EU membership on Saturday morning, it will face a variety of daunting new challenges, not least the precise nature of its future relationship with the EU. And it is this context that the government will be hoping that the positive tone of the inscription on the new 50p coin will be reciprocated both in Brussels and in the wider world beyond.

In terms of Britain’s future relationship with the other 27 remaining member states, it is important to remember that Britain is not leaving Europe. Irrespective of the terms of the future trading relationship to be struck in the forthcoming negotiations that are due to be completed by the end of December, Britain is keen to maintain a constructive relationship with the EU – one that goes well beyond trade and encompasses other key areas of bilateral cooperation, such as security.

Britain’s desire to leave on friendly terms can be seen in the attitude Mr Johnson has adopted since becoming prime minister last July, in which he has deliberately taken a non-confrontational tone with his EU counterparts, frequently referring to them as “our European friends".

The EU, too, has much to lose by not reaching a mutually beneficial accord with London.

The cheap quip this week by Ireland's prime minister, Leo Vadadkar, that Britain would become a “small country” following its departure could not be further from the truth. Post-Brexit, it will still retain its seat as one of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, giving it enormous political and diplomatic clout on the world stage.

In addition, Britain's military and intelligence services remain the envy of Europe. It is the only European country apart from France that boasts its own nuclear weapons arsenal, while its armed forces – which are about to see two 65,000-ton Queen Elizabeth-class aircraft carriers enter service – still remain Europe’s most powerful military force. These are considerations that will need to be factored into the EU’s calculations as it ponders its future relationship with Britain as, without ongoing British support, Europe could find its security requirements seriously compromised.

Add to this the fact that the British economy, which is currently growing at a far greater rate than the Eurozone and is projected to continue doing so by reputable institutions like the IMF, remains the fifth-largest in the world. And it is clear that it is very much in the EU’s interests to reach a reasonable post-Brexit settlement with London.

That said, Mr Johnson and his ministers have made it abundantly clear that they see Brexit as an opportunity for Britain to sign new trade deals with the rest of the world, with a wide-ranging UK-US agreement being their top priority. The Gulf is another area, as well as Australia, India and Japan, where Britain will be hoping to expand its existing trade ties.

So, rather than having regrets that Britain is finally leaving the EU, there are many reasons for optimism that Brexit will ultimately prove that the people made the right choice after all.

Con Coughlin is the Telegraph’s defence and foreign affairs editor