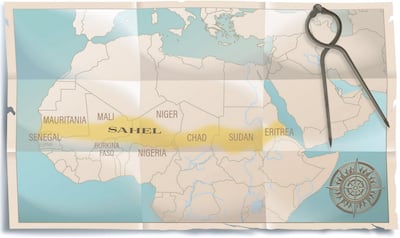

As France mourns 13 soldiers killed in a helicopter collision on Monday during a nighttime operation against extremists in Mali, many French citizens will be wondering what they died for. They have good reason to ask. After nearly seven years of non-stop security operations across the Sahel, from Mauritania's Atlantic coast to the eastern reaches of Chad, a military solution to the conflict is as elusive as ever.

In fact, the Sahel's security situation is going from bad to worse. As United Nations secretary general Antonio Guterres declared earlier this month, terrorist groups are in the ascendancy across the region, nowhere more so than in Mali and Burkina Faso. Yet the UN chief's words of warning merely underscored what is already widely known: that the security situation is deteriorating. The rise in chaos is obvious from the daily deluge of bleak headlines. This month alone, dozens of government soldiers and citizens have been killed across Mali and Burkina Faso by militants hellbent on eliminating any opposition to their efforts.

Despite growing alarm in the corridors of power, stretching from the UN’s headquarters in New York to France’s Ministry of the Armies in Paris, clear solutions to the crisis are far from obvious. Monday's fatalities, when a Tiger attack helicopter collided with a Cougar military transport helicopter, was the deadliest incident since the France-led intervention began in 2013; a total of 38 French soldiers have lost their lives to the conflict to date. French Defence Minister Florence Parly, who arrived in Mali on Wednesday to lead the investigation into this week's fatal collision, declared her nation would "stand tall, united, resilient" and "continue the fight". But the reality is that France's armed forces are already overstretched across the vast Sahel region and the government of president Emmanuel Macron is loathe to devote even more resources and manpower to a problem with no solution in sight.

Instead, France has settled for much more attainable prizes: eliminating high-value targets from Al Qaeda and ISIS-backed terrorist groups and preventing the collapse of regional allies to avoid a repeat of what happened to Mali in 2012, when Tuareg rebels captured major towns in the north in a coup and clashed with Islamists, plunging the country into chaos.

As the French military, which first intervened in 2013, now tries to hold the line, regional solutions to the crisis are failing. The G5 Sahel Joint Force, a multinational counter-terrorism unit comprising troops from Chad, Niger, Mauritania, Mali and Burkina Faso, is struggling for relevance. Promoted by Paris to be an “African solution for an African problem”, it is bedevilled by financial and operational shortfalls. The force is primarily funded by France, the EU and the US, with other countries making smaller contributions. But promises from international donors have not been kept and there is no predictable mechanism for annual funding, casting doubt on the force’s survival as international interest inevitably lags.

The results have been predictable. Morale is low and operations have been few and far between. Thus, instead of a solution, the G5 Sahel force is no silver bullet for Paris, which hoped it could one day alleviate the burden for France’s overstretched Operation Barkhane, launched in the wake of the coup with 4,500 troops. To underscore the G5 Sahel force’s deep troubles, it suffered a humiliating and deadly attack on its headquarters in Sevare, Mali, in June last year. Shortly afterwards, it moved its headquarters away from the battlefield to Bamako, the country’s capital located in the more stable south.

International solutions have also proven feckless. The UN mission in Mali, comprising 15,000 troops and in place since 2013, is powerless to stem the rising tide of violence. With no peace to keep and no mandate to target militants, it has become a sitting duck, earning the undesirable moniker of the organisation’s deadliest peacekeeping operation. The bloodshed has even prompted several contributing states to pull their troops from the mission.

Moreover, the UN mission’s biggest sin is arguably how much money it sucks up. Running at $1 billion a year, the peacekeeping mission dwarfs the G5 Sahel Joint Force, which has struggled to secure a fraction of the UN mission’s considerable funding. This reality has not escaped Sahel leaders, who are increasingly voicing frustration, prompting allies like UN chief Mr Guterres to speak up on their behalf.

In a report released earlier this month, he expressed concern about the "impact of persistent equipment and training shortfalls on [the Sahel force's] operations", adding: "I remain deeply concerned about the spiralling violence in the Sahel, which has spread to coastal states of West Africa along the Gulf of Guinea". Nevertheless, as UN forces drown with an unclear mandate, it is local troops – the very ones actively engaging in conflict and dying in clashes against militants – who most acutely lack the resources, training and funding to succeed.

The harsh truth is that the combined efforts of France’s military, regional states and the UN will never be enough to wholly reverse the Sahel’s palpable decline into chaos. This is because at the conflict’s very heart is a political failure that cannot be plastered over with a military solution. As it stands, the 2015 peace talks in Algiers, Algeria, which technically led to an agreement among the various warring parties, remains largely unimplemented. Instead, Mali’s government is weak and has outsourced some of its security mission to militias with nasty human rights records.

Just as troubling, many of Bamako’s agents in the restive and remote far north are mistrusted at best, and despised at worst, by the local populace. Large swathes of territory across northern Mali are either entirely absent of leadership or subjected to predatory officials and security forces known more for their corrupt appetites and the dangers they pose to locals than for effective governance.

Mali’s festering political woes are giving terrorist groups plenty of ammunition to exploit. Disaffected youths from minority groups long alienated by the central government have been prime targets for militants to make inroads into these communities and find new recruits. Additionally, growing governance vacuums in northern Mali and Burkina Faso – which is increasingly bearing the brunt of Mali’s never-ending crisis – enable militants to tap into the lucrative, informal gold-mining sector, leaving them flush with cash to buy more weapons, as well as the hearts and minds of angry local communities.

As terrorist groups in the Sahel increasingly take the upper hand, the international community will be faced with a stark choice: it can sit passively and see just how much worse the situation will get or it can overhaul the existing counter-terrorism effort. But if things continue to slide, unforeseen events might well force the international community’s hand. For example, Burkina Faso will hold presidential and parliamentary elections in November 2020. As militants thrive on chaos, they will seek to disrupt and undermine the legitimacy of the polls by carrying out attacks on polling stations and election staff. It is unclear if the struggling Burkinabe military will be able to ensure free and fair elections across its territory, most of which was recently declared a “no-go” area by France’s ministry of foreign affairs in a travel security update.

Militants are also thinking beyond Burkina Faso. They are casting their eyes towards coastal West Africa, which until recently had largely escaped the consequences of the Sahel’s instability. In response, countries like Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo and Benin are bolstering their northern flanks in fear of a spillover effect.

They have good reason to be afraid. With the deadly March 2016 attack in Grand Bassam, a tourist town close to Abidjan in Ivory Coast, and the kidnapping in May this year of two French citizens and murder of their guide in northern Benin, the risk of attacks in these countries is no longer theoretical. Militants are actively trying to burrow into these countries to commit future strikes. And their motivations are clear. These states have relatively sizeable western expat communities and tourists, providing attractive targets. Many of these West African governments are close partners of Washington, Paris and London, allowing them to inflict damage on allies of their main enemies. And lastly, by attacking these southern coastal countries, it will further stretch already thin regional and international counter-terrorism efforts as resources and manpower are spread out across many more thousands of miles and yet more states.

All the troubling evidence in recent months leads to one clear conclusion: the fight against terrorism in the Sahel requires a new and co-ordinated effort by the international community. Until that happens, terrorist groups will use their current advantage to deadly effect in an ever-growing area.

Stephen Rakowski is a sub-Saharan Africa analyst at geopolitical risk consultancy Stratfor, focused on security, political and economic trends across the continent