In the fortnight since Saudi Arabia opened up to tourists for the first time, more than 24,000 visitors have poured into the country, drawn by the rich culture and heritage of the heartlands of the Arabian Peninsula. These lands have for millennia been at the crossroads of the ancient civilisations of the Fertile Crescent, the river-valley kingdoms of Iraq and Egypt connected by the Levant. Arabia, visited by Babylonian kings and guarded by Roman legions, was the setting for the legends of King Solomon’s mines and the dying ambitions of Alexander the Great. The archaeology of Saudi Arabia is, as a consequence, every bit as splendid as its better-known neighbours.

Indeed, many visitors will be surprised to learn that Saudi Arabia has some of the most significant archaeological sites in the Middle East. This is largely because the Kingdom was never subject to colonial rule. The 19th century European antiquarians who picked over the bones of the Fertile Crescent unwittingly created a canon of ancient civilisations. That canon almost entirely omitted the Arabian interior, which lay beyond the reach of European empires. Visitors to the British Museum in London and the Louvre in Paris are familiar with the antiquities of Mesopotamia and the Nile Valley. Arabia, in stark contrast, remains terra incognita.

Last year Al Ahsa Oasis was named a Unesco world heritage site, taking Saudi Arabia’s total of historically recognised cultural sites to five, with a further nine on the tentative list. Unesco – or the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation, to give it its full name – was set up after the devastation of the Second World War to promote a humanist vision of a universal legacy. World heritage sites are monuments or landscapes chosen as signposts of our collective human journey or because they embody our shared human experience. Among the most famous are Stonehenge in the UK, the Pyramids in Giza and the Taj Mahal in India. What is special about Saudi Arabia’s Unesco sites is that they don’t simply tell the national story of the Kingdom; they also speak of its place in the world and its contribution to the grand sweep of history.

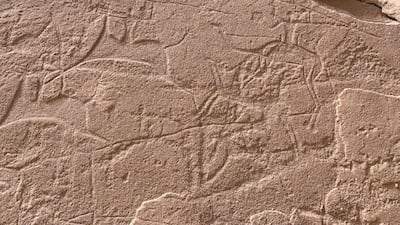

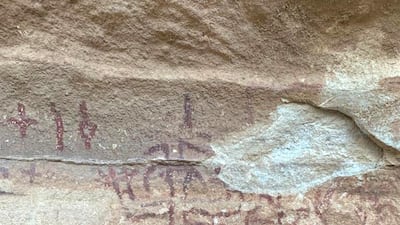

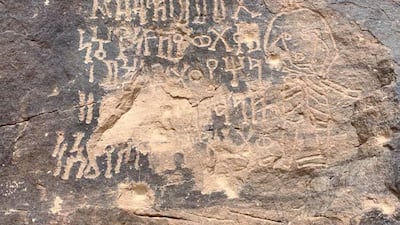

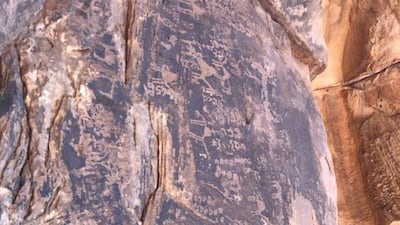

Saudi Arabia has one of the greatest repositories of ancient rock art to be found anywhere in the world. The walls of the dry riverbeds or wadis meandering through the hills and mountains of western Arabia are covered with a dizzying array of images laboriously chiselled into the rock, including gods and goddesses, beasts both mystical and mundane, together with thousands of inscriptions in myriad ancient scripts. The rock art of the Hail region was inscribed on the list of world heritage sites in 2015, the same year that the rock art of Hima near Najran in southwest Saudi Arabia was placed on a tentative list, both featuring a remarkable sequence of images stretching back to the dawn of human civilisation.

The oldest archaeological site on the tentative list is Dumat Al Jandal, modern-day Al Jouf, an oasis at the head of the Wadi Al Sirhan connecting Arabia to the Levant. In the eighth century BC, it was known as “the city Adummatu, fortress of the Arabs”. Here was found the capital of the kingdom of Qedar, mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, ruled over by a series of warlike Arab queens – including Zabiba and Shamsa – who fought against the Assyrian empire. The importance of Qedar and its queens cannot be overestimated: this was the first Arab kingdom to emerge into the flickering half-light of ancient history.

More important still to the formation of an Arab identity are the sites of Al Hijr and Al Faw, both about 2,000 years old, when Arabia grew fabulously wealthy on the frankincense trade with Rome.

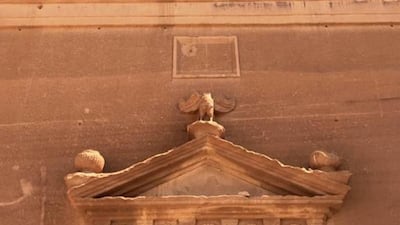

In 2008, Al Hijr – also known as Madain Saleh – became the first Saudi location to be inscribed on the list of Unesco world heritage sites. It is widely regarded as the jewel in the crown of Saudi archaeology. Finds from the nearby oasis of Al Ula are currently on display in an exhibition aptly named Marvel of Arabia in the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris. The enigmatic tombs of Al Hijr, with their splendid pseudo-classical facades hewn into eerie rock formations, belonged to the second city of the kingdom of Nabataea. This kingdom flourished from the third century BC to the second century AD, between the northern Hejaz and southern Levant. Its capital, Petra in Jordan, is one of the most famous archaeological sites in the region. Significantly, it has now been shown that the Nabataeans were Arabic speakers but wrote their inscriptions in Aramaic, the lingua franca of the ancient world. After the Romans annexed Petra in 106AD, they stationed a garrison in Al Hijr – mentioned in a Latin inscription found at the site – so that the frontiers of the Roman empire reached from the mists of Scotland to the deserts of Arabia.

The caravan town of Qaryat Al Faw is also on the tentative list of world heritage sites. Among its highlights is a palace decorated with lively frescoes painted with Dionysian scenes, with local notables reclining on Grecian couches beneath an arbour of vines. This was the home of the famed Imru Al Qays, the poet-prince of Kinda, whose longform poem became the starting point of Arabic literature. It is said that the words were sewn in gold on Coptic linen and hung on the walls of the Kaaba in the days before Islam, when it served as a sanctuary. The Arabic script used to write the poem developed out of the Nabataeans’ alphabet: a vivid testimony to the living legacy of these cultural sites.

The arrival of Islam transformed the Arabian Peninsula, which had long been a crossroads of trade, into the beating heart of an expanding global empire. Ancient caravan routes were transformed into pilgrimage routes that brought the faithful to Makkah for Hajj. The routes linking the Hejaz in the West to neighbouring Egypt, Syria and Iraq have all been individually inscribed on the tentative list. Their caravanserai were lavishly patronised by a series of caliphs and royal women during the golden age of Islam. The Syrian route was used by Abd Al Malik, the Umayyad caliph who built the Dome of the Rock in Palestine, and the Iraqi route was so richly improved by Zubayda, the wife of the Abbasid caliph Harun Al Rashid celebrated in 1001 Nights, that it was renamed in her honour.

The Unesco world heritage site of Old Jeddah, meanwhile, developed as the port of Makkah. Pilgrims from distant Spain and Morocco or India and Indonesia arrived by boat after long and arduous voyages. The city was transformed by the Mamluk sultan of Egypt, Barsbay, who in 1426AD re-routed lucrative trade from India through Jeddah.

______________

Archaeology of Saudi Arabia:

______________

The population of Jeddah, already a cosmopolitan blend of the Arabian Peninsula and Indian Ocean, grew wealthy as a result. The close connection with Egypt endured through the Ottoman centuries, when imperial patrons and local elites constructed elegant mansions designed with mashrabiya, beautifully carved wooden screens of Egyptian inspiration, many of which survive to this day within the Mamluk walls of the old city.

This brings us to the dawn of the 20th century and the close of this brief survey of the key cultural sites of Saudi Arabia recognised by Unesco for their universal significance. Much more could be written about these and the many other sites of the Kingdom now accessible to international tourists. Frankly, Saudi Arabia has an embarrassment of riches, owing to its unique position at the crossroads of the Middle East – the cradle of civilisation – and the heart of the Islamic world.

Dr Timothy Power is an archaeologist and historian focusing on Arabia and the Islamic world and a consultant to the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism. His forthcoming book A History of the Emirati People will be published in 2021 to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the Emirates