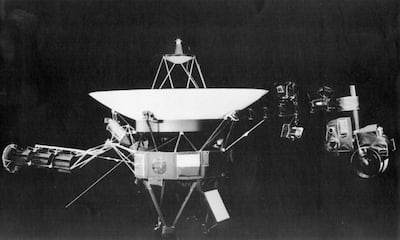

When the Voyager missions were sent by Nasa on their grand tour of the solar system in 1977, they went into space with messages and photographs from Earth, in case either probe bumped into another civilisation.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, which are now both comfortably more than 10 billion miles away from home and still recording data, went into deep space with an eclectic set of images stored on a golden record, including photos of the Great Barrier Reef and rush hour traffic in Thailand. Those pictures were supplemented by a mixtape of music, welcome messages recorded in 55 languages, including "greetings to our friends in the stars" in Arabic, and a note composed by then US president Jimmy Carter. One day these windows onto our world may be discovered by another lifeform.

Earlier this month, another time capsule began accepting deposits again after a months-long pause triggered by this year’s pandemic.

Imagined as a repository for the world's most important information, the Arctic World Archive on the Svalbard archipelago, which is midway between Norway and the North Pole, is a cold storage vault in which great works are being kept for future generations. The AWA is an off-the-grid, low carbon footprint and disaster-proof space set deep inside a disused coal mine.

Last week, Unicef deposited a copy of a petition of support, containing thousands of signatures for the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a duplicate of which is also kept in the facility. Several cultural entities made deposits at the same time, placing archived documents, literary works and art databases into the vault.

The project, which is run as a commercial operation, has been brought into life by Piql, a data preservation and digital film entity. The company says the deposits contribute to a richer picture of our era and serve to protect world memory for centuries to come.

The AWA’s intriguing location and cutting-edge digital film storage techniques could easily have been imagined on the pages of a Hollywood script, but the project’s broader impulse raises real-world questions about what should be preserved and for what purpose?

Much of global development walks a fine line between preservation and progress. Most UAE residents, for instance, are profoundly aware of that balance, as developers seek to improve our communities and weigh up what to hold onto and what to discard. It is a tough puzzle to solve.

The same goes for global memory more broadly. Much of history is written as an exercise in omission and compression. Plenty that should be kept is set aside or lost.

The Voyager missions bore the message of Mr Carter to other civilisations – his typewritten words noted that “we are attempting to survive our time so we may live into yours” – but which other presidential words should we keep for eternity?

Should we lay down the inspirational "slip the surly bonds of Earth" eulogy by Mr Carter's successor, Ronald Reagan, after the 1986 Challenger Space Shuttle disaster or Donald Trump's memo to the Proud Boys to "stand back and stand by" in last month's tetchy first US presidential debate? Both statements paint pictures of how we were and how life is now, even if they exist on sharply different points of the scale of acceptability or empathy.

The same is true of this year in general. What version of this year should we preserve for eternity: is it the community spirit of the early months of people sheltering at home or the protests in Europe against new restrictions of movement orders imposed in the autumn? Should we remember the failures of some world leaders in the pandemic or the compassion and decisiveness of others? A combination of the unequal parts good, bad and indifferent continuously shapes our world.

On a Zoom call a few days before this month’s deposit in the AWA, Rune Bjerkestrand, Piql’s managing director, talked to me about some of these issues.

Punctuated by the digital glitches that have become so familiar to us all in this year of bouncing from one videoconference call to another, the occasional fragility of the medium only served to underline the burden of responsibility that comes with preserving memory. Our world, both digital and real, is vulnerable. We live under near constant threat of loss of information, livelihoods and meaning, either by accident or sometimes by willful destruction.

Mr Bjerkestrand says that “we think the owners of the information should decide what’s important” but noted that the project has prompted deeper discussions about what is appropriate to curate and what has value for cultural heritage.

Around the same time as the AWA reopened, the Oreo biscuit company inaugurated its own Global Vault on Svalbard as an apparent marketing stunt to protect the brand's cookies from possible destruction by asteroid 2018VP1, a small fridge-sized rock that is expected to fall towards Earth in early November. Nasa tweeted in August that 2018VP1 poses no threat to the planet, so the brand is in no immediate danger of extinction, unless consumer tastes change rapidly.

But in a year when many people have lost more than they have gained, perhaps a heightened sense of protecting what we have is only natural – be it cookies or a UN charter. Facing the howling winds of the pandemic, self-preservation and a deeper commitment to conservation now seem like appropriate instincts in our wild world.

Nick March is an assistant editor-in-chief at The National