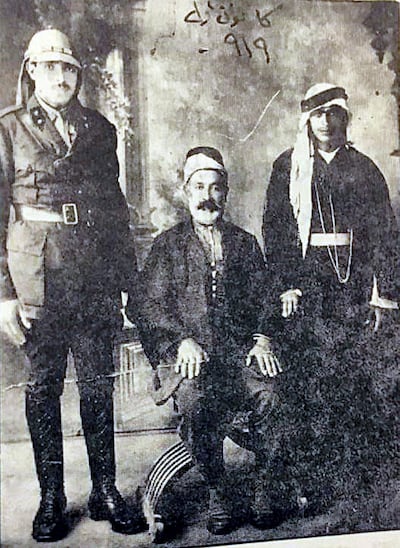

"Iraq is a garden and the English are its gardeners." Those are the words of a British Major Yeats, administrative inspector in the governorate of Anbar, as he addressed a group of dignitaries from the town of Rawa in April 1921. My grandfather, Abdul Jabbar Al Rawi, was among them, listening to this British officer attempt to persuade ordinary people to look more favourably on their occupation less than a year after a revolt had been put down.

Speaking in classical Arabic to the men and shaking the cane he held, Major Yeats went on to say: “Iraq is like this stick. To grow leaves and bear fruits it needs soil restoration, fertilisation and watering. In order to achieve this target, we need your co-operation."

Iraqis in those days were fervently patriotic and were desperate to have their own government, according to the memoirs of my grandfather, which two generations of my family are currently working on translating into English for publication. My grandfather would himself serve in an Iraqi government after independence, which would not come until more than 10 years had passed after Major Yeats' intervention.

In 1921, however, nothing was certain about an independent Iraq. After the revolt, the British had turned to Prince Faisal, who had successfully led the Arabs against the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, and he would become Iraq’s king under their administration. Exiles living in Hijaz in Saudi Arabia – many had fled after the failure of the revolt – asked Prince Faisal how he intended to rule. According to my grandfather, one of those exiles was told that he would rule under a British mandate and not seek to do so independently. This was deeply disappointing to those who had been fighting for complete independence.

However, pragmatism won over and Iraqis rallied behind their new king, believing it better to have some hand in their own governance than allowing the British to have direct control over their country and their lives. Even with the benefit of hindsight, I look back a century ago and feel a sense of anger at how all this played out; angry at the now abhorrent colonial mindset of Major Yeats. I struggle to accept the gall he had to tell a proud and venerable people that they were incapable of handling their own affairs. I am also saddened that one hundred years on, Iraqis are still having to compromise over their sovereignty as external powers attempt to hold sway over their lands.

Knowing what we know now, I wonder if it would not have been better to keep fighting the British until it became too costly for them to stay. Would it have been better to have struggled longer, despite the cost, for the opportunity to begin Iraq's modern incarnation well before the Middle East became burdened with challenges such as the Israeli occupation of Palestine?

However, I must concede that ultimately foreign powers would always dictate Iraq's future; first during the Cold War, then after Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the US-led invasion that toppled his regime in 2003. Since then, Iran has worked to hold sway. Today, the low-key conflict between Washington and Tehran is arguably the most influential factor in what kind of country Iraqis will ultimately be left with.

Surrendering to a sense of pragmatism in 2020 would not look all that different from the compromises made in 1921. Instead of armed revolutionaries fighting a foreign power, we now have peaceful demonstrators in the streets calling for a better standard of living and an end to foreign intervention in Iraqi affairs.

A new government under Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi offers hope that we can tread a path towards this justified goal, just as a new government under King Faisal also symbolised a fresh start and something promising after years of conflict and oppression.

In 2020, our vantage point also means we can look at the mistakes made in the past and be a little more forgiving of those who were still determined to do what they thought was best for their people.

If today’s protesters choose to give Mr Al Kadhimi’s government a chance to try to affect change, they will be doing so based on the best available judgment they have, given how uncertain these times are. On the face of things, it does look like the best option – perhaps, much as backing King Faisal during my grandfather’s time must have also seemed the most logical way forward when options were limited.

Eventually, anti-western sentiment would spill over and a fatal coup in 1958 would be the trigger for decades of instability and bloodshed.

Today, Mr Al Kadhimi has pledged to put Iraq’s sovereignty first. This goal will be hard-won and will be challenged often in the weeks, months and years to come. It is still what the people most deserve, especially after more than one hundred years of hoping.

Mustafa Alrawi is an assistant editor-in-chief at The National