Chinese President Xi Jinping and US President Joe Biden spoke for the first time since last November on a telephone call on Tuesday. According to the Chinese news agency Xinhua, Mr Xi put forward both an offer and a warning: that if Washington wants mutually beneficial co-operation then China's door is open, but if it is adamant on containing China’s development then Beijing is not going to just sit back and watch.

I’m not sure if the US politicians who recently voted to ban TikTok unless its Chinese parent company, ByteDance, sells its controlling stake in the app within six months were taking notice or not. But others are certainly getting Mr Xi’s message.

Singapore’s highly regarded ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute has just released its annual State of South-East Asia report, and for the first time in five years its survey found that a majority preferred China over the US if countries were forced to align with one over the other. It was a slim lead – 50.5 per cent versus 49.5 per cent – but distrust in the US also increased considerably, from 26.1 per cent of those surveyed in 2023 to 37.6 per cent in 2024. China was seen as the 10-member Association of South-East Asian Nations’ most strategically relevant “dialogue partner” (above the US and Japan), and the most influential economic and political-strategic power in the region.

Some of this may be down to the fact that Israel’s war on Gaza – enabled by the US and opposed by China – polled as South-East Asia’s foremost geopolitical concern; but that’s only part of it.

Who else is warming to China? Well, there appeared to be plenty of smiles in the group photos of top American CEOs who had a meeting with Mr Xi in Beijing last week. The Chinese President said that the two countries could help each other’s development and “embrace a brighter future”. Earlier in the week Apple’s chief executive, Tim Cook, could barely contain himself after opening a huge new store in Shanghai. “I love it here, I love the Chinese people,” he said. “I think China is really opening up. It’s so vibrant and dynamic here.”

He wasn’t alone. Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla was reported to have called China “an extremely attractive place”. Hua Chunying, China’s Assistant Minister of Foreign Affairs, posted on social media a series of positive comments from western business leaders such as Mercedes-Benz’s Ola Kallenius, who said: “We have been investing here for more than 20 years … We need to keep trade relations open and vibrant, focus on win-win in terms of economic growth.”

And that’s the key: trade and investment.

I mentioned a couple of weeks ago how Chinese companies had been “flooding” into Malaysia, while separately Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim secured 170 billion ringgit ($35.7 billion) worth of investment commitments during his visit to China about a year ago. China was Thailand’s top foreign investor last year, with pledges of further factories, plants and production bases to come.

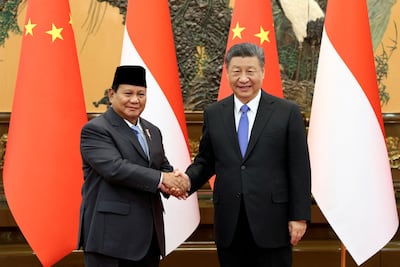

Chinese investments in Indonesia were more than twice those by America last year; they also supported the construction of the Bandung-Jakarta high-speed train, and they are expected to play a huge role in building the country’s new capital, Nusantara, on the island of Borneo. It was no surprise that Prabowo Subianto made China the first country he visited last Monday after becoming Indonesia’s president-elect in February.

It has also been announced this week that Cambodia is going to build a canal that will allow it, for the first time, to ship goods from its capital, Phnom Penh, directly to the Gulf of Thailand, rather than having to transit through the Mekong Delta in Vietnam. No money has been borrowed – a Chinese company will finance and charge for operating it for a period of 40 or 50 years, after which it will be transferred to the Cambodian government. This will, at last, let Cambodians “breathe through our own nose”, said a delighted Prime Minister Hun Manet.

This canal, and Indonesia’s high-speed rail, are examples of what China’s strangely oft-maligned Belt and Road Initiative actually does in practice – enable the construction of big infrastructure projects that developing countries need. No one else is stepping forward to support them. No wonder sentiment towards China is on the up.

But how is this possible? Isn’t the Chinese economy supposed to be in the doldrums, in a slump; choose your cliche from the many headlines in English-language media?

Not according to IMF director Kristalina Georgieva, who recently said: “I see in China today a shift from high growth rates to high-quality Chinese growth.” And not according to Asia Times columnist David P Goldman, who posted this week: “China isn’t collapsing: it’s in transition from the Deng Xiaoping model [farmers become semi-skilled workers] to a high-tech model [63 per cent rate of tertiary education].”

Last month, he observed that “direct exports to developed markets are shrinking”, but “China is knocking the cover off the ball in exports to the Global South”, pointing to a survey that showed China’s exports growing 10 per cent year-on-year, and the huge jump in exports to the Global South far outweighing the losses in developed markets. In fact, wrote one of Mr Goldman’s colleagues: “China’s outbound investment [is] reshaping the global economy.”

We have had warnings about “peak China” for years. A book called The Coming Collapse of China was published – in 2001. Yes, we are all aware of the trouble in the country’s property market and there may very likely be a slowdown in growth. Yet it’s hard to avoid concluding that some of the prophecies of doom are the wishes of Sinophobes rather than genuine predictions.

That’s not the feeling in South-East Asia, as evidenced by ISEAS-Yusof Ishak’s new report. And that didn’t appear to be what was going through the minds of the titans of the American and European corporate world who were in China last month.

Normally western governments are so keen to pay heed to the words of these men and women. Maybe they should in this instance. Because perhaps they have learnt something about the possibility of working with China that leaders in Washington and London need to hear – even if they don’t want to.