There’s no denying it – the shaky smartphone videos showing the darkened interior of a juddering Alaska Airlines 737 Max 9 as it made an emergency landing in Oregon last week are unforgettable footage. The knowledge that they were shot by ordinary passengers is arresting and poignant – people on an everyday flight suddenly found themselves confronting what many clearly thought were their final moments.

It is difficult not to feel empathy with the 177 passengers and crew of Flight 1282; the sight of people buckled up in the Boeing’s depressurised cabin, gripping seat armrests with whitened knuckles as the wind whipped through a forest of dangling oxygen masks is worryingly relatable. It is easy to put oneself in the shoes of these passengers, some of whom composed hurried final texts and videos to send to their loved ones. Their everyday reality had been suddenly and shockingly ripped asunder.

And yet, despite this being a moment of the highest drama, thankfully no one died. Flight 1282’s pilots fell back on their training, maintained control of the aircraft, communicated with air traffic controllers and eventually guided the jet back to Portland International Airport. About 20 minutes after the plane took off, everyone was back on solid ground.

The story of Flight 1282 is still being written and US investigators are trying to piece together what happened. Serious questions are being asked of Boeing and the company’s share price has tumbled as a result. However, if we pull back and focus on the bigger picture of 21st-century aviation, what is striking is not only that it remains the safest form of transport, but that it is arguably one of the most successful examples of global human co-operation in the modern era.

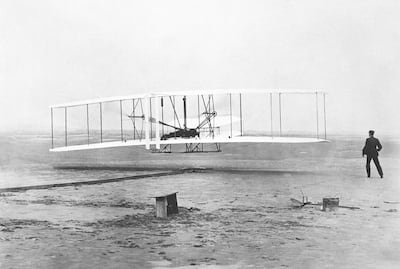

In historical terms, powered flight has not been around for very long. It is a little more than 120 years since the Wright brothers’ flyer made the world’s first powered flight and on May 2, 1952, passengers on a de Havilland Comet were the first to travel commercially by jet plane. Yet despite flying being available to many of us for only a few decades, modern aviation has not only shrunk the world but revolutionised commerce, warfare and technology.

Since that historic 1952 maiden flight, the world’s number of planes and passengers has grown exponentially, apart from the brief hiatus experienced when Covid-19 temporarily halted air travel – and even that pause is well on the way to being reversed. According to figures from OAG, a data platform for the global travel industry, last year’s busiest day for airlines – August 11 – saw them operate more than 18.5 million passenger seats across millions of flights. This is in addition to the millions of non-passenger flights – such as cargo, private and military – that take place year in, year out.

Thanks to significant investment in improving aircraft design, air-traffic control systems, pilot training, weather prediction and satellite communication, these millions of flights now take place with a statistically infinitesimal likelihood of a fatal incident. The numbers bear this out: according to the International Air Transport Association, in 2022 there were five fatal accidents among 32.2 million flights. Every death is a tragedy, but flying on a modern jetliner is probably one of the safest activities one can do, not just in terms of getting from A to B but in life generally.

It is difficult to think of another sector in which such exacting standards in maintenance, oversight, regulation and training are so rigorously enforced. Pilots are tested every few months to make sure their flying skills are up to scratch. The planes they fly are also routinely examined – including going through what’s called a “D check” every six to 10 years in which the aircraft is almost dismantled as part of a thorough overhaul that costs several million dollars. Even passengers are subject to intense scrutiny – there are tough punishments for those convicted of endangering an aircraft and many judges take a dim view of dangerous or disruptive mid-air antics, being quick to hand down fines or even custodial sentences.

What makes the argument for aviation being something of a modern miracle is that most countries – many separated by geography, language or outlook – have largely agreed on a common approach to administering air space, enforcing flight rules, prioritising safety and protecting the integrity of their aviation network. Given that many countries are often rivals in other areas, such as politics, diplomacy or business, it is striking how much general international co-operation there is when it comes to aviation, particularly on safety.

Why then do we fixate on the anomalous number of airplane accidents? It is perhaps that aviation’s incomparable safety record is, ironically, something of a drawback, amplifying the failures and lapses. And most incidents are lapses – only a small proportion of accidents result in fatalities. A recent example is the January 2 freak accident at Tokyo’s Haneda airport where incoming Japan Airlines Flight 516 burst into flames after hitting a coast guard plane that had been sitting on the runway. Despite the nightmarish scenes of the burning Airbus A350 and the tragic deaths of five crew members on the smaller plane, all 379 passengers and crew from Flight 516 survived thanks to the rapid emergency evacuation overseen by the flight’s well-trained crew members. Again, the system worked.

This is not to say there are no issues in aviation that need to be addressed. The increasing frequency of flights has led to some unions speaking out about the potential danger of pilot fatigue. However, even on this issue, the industry appears to be responsive; only this week it was reported that India’s aviation regulator now requires pilots to have a mandatory 48-hour rest period at the end of a working week, an increase of six hours.

I don’t think that stories of planes crashing or having near misses will ever lose their power to grab our attention. At the time of writing, the Alaska Airlines story is still running in the US media. I can understand this; as someone who is still something of a reluctant flyer, I know that travelling in a cramped metal tube at 40,000 feet feels precarious and unnatural. Sadly, the part of our psychology that understands the facts and realities of aviation safety is not connected to the more elemental parts of our brain that react with visceral alarm to sudden turbulence, storms or abrupt turns.

Nevertheless, I can’t help but wonder that if aviation’s culture of rigour, high standards and co-operation were to be applied to other critical fields, it would go a long way to solving many of the world’s problems. Now that’s a final call I could get on board with.