If you do an online search for the Great Horse Manure Crisis of 1894, you will find some exquisitely written, but ultimately nauseating, passages about the grim and potentially deadly pollution of the period.

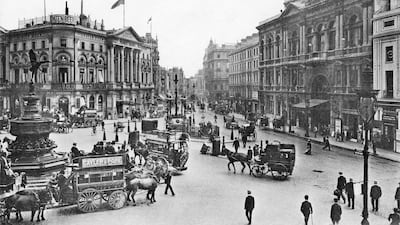

They describe how the sheer volume of horses required to run city transportation in Europe and North America at that time had led to the streets being “literally carpeted with a warm, brown matting … smelling to heaven”.

That gem of a line is from The New Yorker magazine, by the way.

It is claimed that The Times newspaper of the day made the following prediction in print: “In 50 years, every street in London will be buried under nine feet of manure.”

Of course, we never discovered if they would prove to be correct as the motor car usurped the horse in the 20th century.

There is also some debate among historians about the actual extent of the crisis. The manure problem may have been exaggerated, and there is also the suggestion that the deeper cost of the reliance on horse-drawn transportation was the need to maintain a large-scale agricultural industry geared towards keeping the animals fed, which was an inefficient use of land and resources.

In any case, early motor cars were marketed as a “cleaner” alternative to literal horsepower. Yet cars have played a part in fuelling our current environmental crisis and, as the world tries to work together to limit global warming caused by greenhouse gases, we are searching for a solution to the pollution caused by cars.

In Europe and the US, consumption of petrol and diesel fuel in the transportation sector is a significant source of carbon dioxide emissions.

Transport was responsible for about a quarter of the EU’s total CO2 emissions in 2019, of which 71.7 per cent came from road transportation. In the US, cars accounted for about 30 per cent of total CO2 emissions last year. Globally, the emissions produced by passenger cars have been steadily rising over the past 20 years in particular.

Obviously, no one predicted the above outcome way back in the 19th century or even the early 20th century.

In our current climate emergency, the electrification of transport and the phasing out of the internal combustion engine that saved us more than a century ago are now being put forward as the solutions to our petrol and diesel driven woes.

How quickly will the electric car put the internal combustion engine out to pasture? The trend indicates it may be sooner than expected. Already, global sales of petrol and diesel cars have peaked and growth is now led entirely by electric vehicles.

According to a Bloomberg Green analysis of adoption rates around the world, 24 countries have passed 5 per cent of new car sales powered only by electricity.

The 5 per cent threshold signals the start of mass adoption. Canada, Australia, Spain, Thailand and Hungary as well as the US, China and most of Western Europe help make up the 24 who have crossed it.

IDC, a market intelligence provider, is forecasting 14 million units to be sold worldwide in 2023 – about 18 per cent of the overall market. Autonomous driving technology will also accelerate this going forward, IDC said.

While car makers might be pleased with themselves, I cannot but help think of the people of 1894 and what they could not know – and I wonder what it is we, in 2023, also do not understand about the choices we are making.

Global warming, greenhouse gas emissions and the melting polar ice caps were not part of 19th-century thinking. So, the motor car being presented as the answer to their horse-driven problem would have seemed like an elegant solution. It only served to kick the can down the very long road to the 21st century and we now know the impact of embracing the internal combustion engine.

It is, of course, not as simple as that. Motorisation has brought many benefits too. Yet we are now being advised that EVs can help alleviate our modern pollution crisis. Of course there will be benefits from this.

However, we should also ask how EVs might bring us more problems in the future that could put our lives at risk.

The first thought is about resources and that despite not being a gas guzzler, an electric car needs to consume other things. For example, each EV needs graphite, cobalt and lithium for its batteries.

Reuters reported in June that manufacturers, including Tesla and Mercedes, were seeking graphite supply from outside China, which is the dominant producer. New graphite producers, such as Madagascar and Mozambique, are set to emerge as powers in this sector.

The consequences of such developments could be myriad and both negative and positive. Could a race for such resources cause more conflict while creating wealth for generations? Definitely.

Could the widespread use of electric cars help usher in a new and bigger crisis than global warming? You don’t need to hear it from the horse’s mouth to know the answer to that question. Yes, it very well could.