After my latest European tour, I’m back in the US and preparing to celebrate Independence Day with family. As American flag-waving peaks this week, it’s hard not to see the extent to which US leaders prize their own independence while seeing that same quality as deeply problematic in key allies.

Consider Turkey, which, since Moscow launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, has smartly walked a diplomatic tightrope between the two combatants.

Ankara has sent Bayraktar drones and other military supplies to Ukraine, where it is also building a drone production facility. Meanwhile, Turkey has continued to rely on Russian energy supplies and increased trade with Russia by more than 90 per cent, according to the Atlantic Council. Last summer, Turkey led negotiations on a joint grain deal that Russia is threatening to allow to expire later this month.

The latest news to ruffle feathers is a Wall Street Journal report revealing that sanctioned Russian ships have made more than 100 stops in Turkish ports over the past year. The port calls have continued in recent weeks, even though the ships may be transporting military goods. Several are owned by Russian firms linked to past arms shipments and some stopped at an Iranian port where Russian ships have previously picked up Shahed drones.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s annual two-way trade with Russia is now over $60 billion, showing how Ankara has in part enabled Moscow to survive economically. Yet Russia’s trade with another US ally, Greece, has taken an even bigger leap – increasing by 104 per cent.

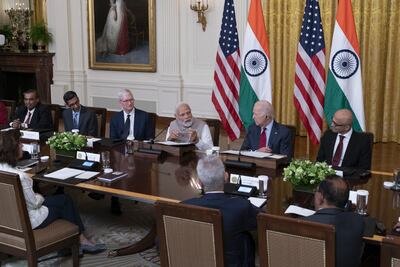

What’s more, India is by far the global leader on this count: its trade with Russia is up by nearly 250 per cent. So why does Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi get a state dinner while Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan gets the cold shoulder?

Likely because an Indian alliance is a useful counter to a rising China and the two governments just finalised major tech and defence deals. Turkey-US ties have been largely defined by defence since the former’s 1952 accession to Nato, thanks to Ankara watching the alliance’s southeastern flank and maintaining its second largest army.

If Turkey, after buying Russian-made missile defence systems in 2018, were found to be allowing the transport of sanctioned Russian goods, which may meet the definition of providing lethal aid, Nato and Washington would have good reason to feel a bit miffed. They could just point to Turkish Ambassador to Nato Basat Ozturk’s recent article for a US think tank, in which he said Turkey’s allies needed to show “full and genuine solidarity”.

It’s par for the course for this bickering couple in recent years: sanctions over Turkey’s S-400 missile defence systems purchase; former US president Donald Trump threatening to destroy Turkey’s economy; Mr Erdogan threatening to expel Western envoys; Turkish frustrations over US co-operation with Syrian Kurdish militants (SDF) it sees as aligned with a Kurdish terrorist group (PKK).

The list goes on, and top Turkey watcher Steven A Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations argues that US and Turkish interests have diverged to the point that the US military’s free and full use of the latter’s Incirlik air base is “no longer assured”. Given that the US keeps some 50 tactical nuclear weapons at Incirlik, this is not a minor concern.

But the more pressing matter is Sweden’s accession to Nato, which the alliance hopes to finalise at next week’s summit in Vilnius. Turkey has linked its approval to Stockholm taking a harsher line on terrorism and may also be angling for US F-16 fighter jets and a favourable move in terms of geographical nomenclature.

This aligns with the transactional foreign policy Turkey has pursued for years. And while many point to Ankara’s reported violations of free speech and the rule of law, which fly in the face of US President Joe Biden’s advocacy for democratic principles, Turkish foreign policy has in the past couple of years seemed to lean towards the West, with robust support for Ukraine and rapprochement with Israel, the Gulf powers and Armenia.

Another development may now shape Nato talks. Sweden allowed a protester to burn a Quran outside a Stockholm mosque, eliciting sharp Turkish criticism, in addition from other Muslim-majority countries.

Yet it’s the port calls that loom largest, coming on top of the news that Turkey exported to Russia tens of millions of dollars in military supplies, including generators, vehicles and electronics. That March report spurred G7 pressure, which in turn prompted Turkey to agree to stop the shipment and transit of sanctioned western goods to Russia.

If these Russian port calls do indeed represent a circumvention scheme, Western powers may be pressed to deliver a harsh response. “Things could blow up,” is how a former top Turkish official put it. It would be not the first time Ankara may have helped a US foe evade sanctions – that would be the oil-for-gold scheme with Iran.

America's case against Turkey’s state-run bank Halkbank reached the Supreme Court in April and is now back with a lower court on appeal. The fine could be significant, which would be a headache for Ankara given its troubled economy and crippling foreign debt.

The Turkish lira reached yet another record low of 26.10 to the dollar last week, even after regulators sharply increased interest rates. The next few days will see a flurry of Sweden-Nato sit-downs.

On Wednesday, Mr Biden hosts Sweden’s prime minister at the White House. Nato Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg talks on Thursday with senior officials from Turkey, Sweden and Finland. Finally, on Friday, Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan is set to meet his Swedish and Finnish counterparts in Brussels.

With any luck, the stick of possible US sanctions and a major Halkbank fine, plus the carrot of American-made F-16s, will in the days ahead enable an amicable resolution to the Sweden stand-off. If not, we might see some post-Fourth of July fireworks.