Last weekend’s declaration of support for ISIL by the Tehreek-e-Taliban (TTP), better known as the Pakistani Taliban, signals a new phase in the insurgencies in Pakistan and Afghanistan. This strategic link-up between ISIL and militants further east is an ominous development not only for US and Nato forces in Afghanistan, but also for the regional powers near the conflict zone.

The TTP’s expression of sympathy for ISIL is a testament to the appeal of the self-styled “caliphate”, which is presenting itself as a more dynamic and aggressive force than established groups such as Al Qaeda.

Early last month, there were reports that ISIL leaflets had been distributed in Peshawar and nearby Afghan refugee camps. The leaflets claimed that the “caliphate” established in Syria and Iraq should be extended to Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia. In addition, a group calling itself the Islamic Organisation of Great Afghanistan sent a video to Radio Free Europe in which it declared itself to be willing to fight for the ISIL leader Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi. The apparent realignment of the militant threat can be seen partially as a response to the US-led air campaign against ISIL and the recent signing of security agreements between the US, Nato and the Afghan government.

Although these accords provide for a continued western military presence in Afghanistan until 2024, there are doubts over the willingness of the US and its allies to confront a renewed militant threat.

President Barack Obama has to balance the Pentagon’s enthusiasm for continued involvement in Afghanistan with the war-weariness of the US public. An ABC News/Washington Post poll in May suggested that while a narrow majority of US citizens favoured offering help to train the Afghan military and police, two-thirds of respondents believed that the war waged since 2001 had not been worth fighting. Although the US could increase troop deployments if the Afghan insurgency is extended, Washington may be reluctant to authorise a future “surge” in the face of domestic opinion.

Other major regional powers are taking a greater interest in Afghanistan given the uncertainty surrounding Nato’s ultimate intentions and the viability of the Kabul government. China, in particular, is becoming increasingly concerned about the prospect of a continued Taliban presence on its western border. Beijing has sought to lead a regional response to extremism through the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which counts Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan as members in addition to China. Potentially, Iran, India, Mongolia and Pakistan, all of which have observer status in the organisation, could join the SCO as full members in 2015 or later.

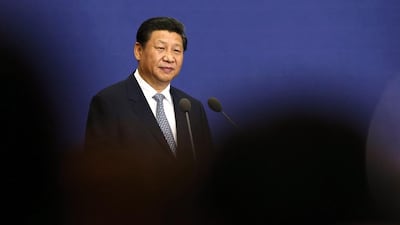

At the SCO conference in Dushanbe in Tajikistan last month, Chinese president Xi Jinping called for the SCO’s members to “focus on combating religion-involved extremism and internet terrorism”. Beijing has also promoted an “anti-extremism” treaty to bolster recent SCO initiatives to create a regional anti-terrorist database and stage joint military exercises. Though the organisation has not identified a specific terrorist threat, there is little doubt that it is focusing on the Taliban and affiliated groups. Significantly, the agreed communiqué published at the end of the Dushanbe conference called for a “reconciliation and reconstruction process” in a “self-reliant” Afghanistan.

Aside from the resilience of the insurgents in Afghanistan and Pakistan, China’s concerns about the rise of regional militancy are partly motivated by separatist agitation in its Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Indigenous Muslim Uighurs have regularly protested against discrimination in favour of Han Chinese immigrants. Recent unrest violently spilled over the borders of Xinjiang in March this year, when Uighur militants attacked a railway station in Kunming in central China. The attack left 31 dead and more than 140 wounded.

If ISIL-inspired extremists in Afghanistan and Pakistan were to disperse into weakly governed areas of central Asia and link up with disaffected Uighurs, theoretically they could pose a much greater threat to China. There is, however, cause to believe that Beijing is seeking to manipulate the extremist threat for its own ends. The Chinese government has explicitly sought to use the SCO to promote its own counter-terrorism doctrine designed to combat what it describes as the “three evils”: terrorism, separatism and extremism.

Bundling in separatism with terrorism is evidently intended to snuff out calls for reform in Xinjiang and the Tibet Autonomous Region. Rather than making a genuine effort to counter potential threats to regional security, Beijing may merely be seeking to use the SCO’s counter-terrorism agenda to target disaffected minorities in China. Recent Chinese state media reports that have accused militant Uighurs of seeking “terrorist training” from ISIL should therefore be seen in this light.

Despite the fine rhetoric heard at Dushanbe, the actual extent of Chinese assistance to the Afghan government has been negligible. The Xi government appears to be more interested in tapping Afghanistan’s natural resources than helping the Kabul government to assert its authority.

The experiences of the British, the Soviet Union and, arguably, the US, in Afghanistan justify the country’s reputation as the “graveyard of empires”. China evidently does not want to fall into the same trap. Nevertheless, neutralising ISIL requires filling a security vacuum in Afghanistan as well as Iraq and Syria. Although reluctant to be drawn into the Afghan imbroglio, China and its SCO partners will have to deal with a potentially grim scenario if Nato fails.

Aside from talks on world trade, next month’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Beijing and the G20 meeting in Brisbane, Australia, should give Mr Obama, Mr Xi and other leaders scope to discuss measures to stabilise Afghanistan and prevent ISIL gaining a foothold in Central Asia.

Stephen Blackwell is an international politics and security analyst