Hafida Latta had completely forgotten about an invitation impulsively extended to some Dutch ladies on a train until they turned up at the front door months later carrying the address in her handwriting.

The foreigners, intrigued by the young girl’s description, couldn’t resist coming to see for themselves the network of rooftops that the women of the Tunisian city of Kairouan used as a highway to visit each other, rather than the city streets below.

Immediately, her grandmother, Rekaya, spurred the 10-year-old into action, ushering the eight unexpected guests inside and sending her off to buy Coca-Cola and provisions for an impromptu feast of lamb couscous, egg briks, makroudh, ghraiba and samsa.

It is, Latta tells The National, the kind of hospitality taken to an art form by generations of Tunisian women that she has sought to emulate around the world as the wife of a British diplomat.

“It’s pretty wonderful to have people you’ve never met come into your home, whether it’s in the garden or around the dining room table, and you’re talking to them as though you’ve always known them, and by the time they leave you’re great friends," she says.

“They all have different religions, nationalities, languages, outlooks. I never shy away because, no matter how much or how little, you always learn something.”

Now 78, as a thank you to the country that provided her with “a wonderful free education”, she has written a cookbook extolling the happiness derived from sitting down to eat with others.

“Not that I have stopped learning,” she says, “but what I was given in Tunisia planted the seed for education in my soul.

"It’s a debt I have to pay back with something that it needs — a cookbook in English that is a bridge to show the people of my adopted country my culinary culture, my DNA.”

In The Tunisia Cookbook: Healthy Red Cuisine from Carthage to Kairouan, Latta has painstakingly juxtaposed 80 recipes and notes on the origins of ingredients with a chronology of world and Tunisian events that she hopes lends a relevance to all readers.

The use of a Shakespearean quote — “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players; they have their exits and their entrances” — reflects the influences from the many empires and ethnicities that came and went over the centuries.

But ultimately, it is a paean to Tunisian women, who “pulled their families through difficult times”, nurtured physical and emotional needs and even shaped identities with what they adapted into a healthy Mediterranean diet.

“I loved doing the research but it took a long time because I’m not really good technologically," Latta says. "I’m one of those silly people who take up a challenge.

"Adrenalin comes in, and I’m so excited because I can’t do it or I don’t know how. It’s something that was instilled in me since I was little.”

Habiba Ben Rajeb, as she was then, was born in 1944 in Kairouan, the first Islamic city in north-west Africa.

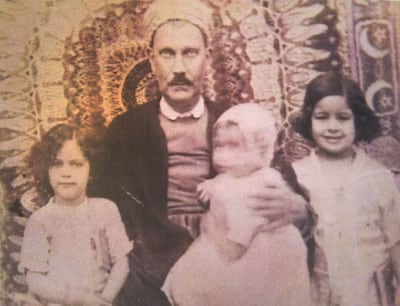

She was the daughter of Cherifa, an uneducated beauty with eyes the colour of turquoise, and Mohamed, a railway manager and businessman 35 years her senior.

Not long afterwards, on the death of Mohamed, Cherifa, still only 21, was turned out with her children, Habiba, three, and two younger siblings, Mohamed and Zohra.

They moved in with Rekaya, the family matriarch and widow of the writer, poet and philanthropist Salah Souissi El Quayrawani, and Cherifa’s sister Mufida, who had been bedridden since contracting polio as an infant.

Family legend has it that the home, with its windows and doors painted blue to ward off evil spirits, and four rooms arranged around a central courtyard, was bought with gold from an enormous pot found by Rekaya’s grandfather while renovating his barn.

“It must have been so big because it filtered through many generations,” Latta says.

“Even I benefited from it because my grandmother bought houses and a terrain of olive trees, which once a year brought in money and olives and olive oil for the whole year.”

All of this, though, wasn’t enough to provide for the four new arrivals now under Rekaya’s care, so Cherifa was put to work weaving carpets and as a seamstress.

One problem remained, however, to which Habiba was deemed the only solution. None of the adults in the house could venture unescorted on to the streets without attracting opprobrium in the patriarchal society.

“That house was full of women: my grandmother, my mother, my poor suffering aunt," Latta says.

"There was no man so they decided that I would be their man. To think of a three-and-a-half-year-old girl walking down the streets is incredible, but there was so much trust and help from everybody.”

With the role came a name change when Mufida compared her with the heroine of a book about a Persian girl called Hafida who helped her family and had a prodigious memory.

The Arabic roots meant protector and, from the Quran, learner, which, as her aunt explained, made it special, unlike the more common Habiba.

“Oh, yes,” Latta recalls saying, “I am going to be a learner.”

Although the birth name remained on all official documents until a British consul in the UAE agreed to drop it from her British passport nearly 50 years later, Habiba, “the miserable little girl whose father left her”, was cast off from that day forward.

As Hafida went about her business, shopping, paying bills and collecting her father’s pension from the bank, she also became known by locals as “the little Souissi”.

About the age of seven, she sold carpets in the market, driving increasingly hard bargains for the efforts that Cherifa put into their creation.

Throughout it all, she was sustained by Mufida, an autodidact who, unable to marry or have children of her own, poured all her love and time into her niece.

“She was fantastic. So the strength I got from my grandmother but my love of learning and curiosity was my aunt," Latta says.

"Here is this woman who can’t move, taught herself how to read and write. I wanted to be like her. It was very empowering.”

Hafida would settle by Mufida’s prone form the moment she got home from lessons outside the city walls at the White Sisters school that served the offspring of French settlers and Tunisians who worked for the government.

Evenings were filled with Arabic, invariably taught through poetry, to plug the gaps in the young girl’s convent education.

There were also thrilling adventures of Sinbad the Sailor and tales of Kairouan’s glorious past that imbued a deep passion in Latta for the city crowned by the oldest-standing minaret in the world.

Most formative, perhaps, were the telling of the folktale about Juha and the Donkey from which Hafida grasped the difficulties of trying to please other people, and Mufida’s firm assertion that all obstacles can be bypassed one way or another.

“Find a bridge or a tunnel or a few different roads,” Latta says. “It might take you longer but you will get there. If we can teach a child this lesson, nothing can stop that child. And, indeed, nothing could stop me.”

Thus instructed, she grew up repeatedly accused by her family of being “big-headed” as she refused to accept the limits that tradition tried to impose on her.

Several attempts to marry her off early were thwarted. After a particularly close call, Cherifa stepped in to give her daughter the possibility of what she never had: a life partner of choice and access to education.

“I was born at just the right time for Tunisia to get independence,” Latta says. “Had I been born one or two years before, I would not have had the chances.

"And I was lucky to have the kind of president who had a sense of what was right.”

If history and timing were on her side, then Latta — “a greedy girl like a sponge” — was absolutely ready to take advantage of any opportunity that opened up

She attained top marks, a prestigious academic award and a scholarship to study law, inspired by Habib Bourguiba, the first post-colonial president of Tunisia who made it all possible with his egalitarian vision for the new republic.

After graduating from l’Ecole Nationale d’Administration in Tunis, she joined the civil service, living in a shared flat with Americans, working as secretary to the minister of culture and information, and teaching Arabic to Peace Corps volunteers.

It was about the time the dream job of assisting the Tunisian delegation at the UN in New York was offered to her that the man she had hoped for came along: David Angus McGill Latta, a diplomat with the British Council.

David, the second son of a Glasgow industrialist father and teacher mother, proposed months later, and Latta says of her response that “there was absolutely no hesitation whatsoever”.

“When I decided to marry a Christian, some of my family were upset," she says. "No matter how hard you try, you cannot please everyone. Impossible.

"I try not to upset others but if they do get upset that’s their choice. So be it. I decided, no, I am going to do what I want to do.”

After a honeymoon in the Scottish Highlands of Inverness, a region much beloved by Latta, the couple embarked on a series of postings — Karachi, Beirut, Dar-es-Salaam, Amman, Abu Dhabi — returning in between to a house in England.

Having given up her hard-fought-for chance to represent Tunisia, she decided to work “in a way that could be rewarding” on behalf of Queen Elizabeth, a woman she admired for devoting herself to the art of irreproachable behaviour at all times.

There were low points, Latta concedes. In Pakistan, as captivating as the colours, smells and sounds were, she sent an SOS to her mother asking for couscous. Four months later, a care package arrived marked “chemical product”, such was the obscurity of the grain back then.

Worse was to come on the outbreak of the Indo-Pakistan War in 1971 that led to Latta being sent home to England with two young sons on an RAF Hercules, and David following later.

The “dazzling parties, excellent food and lively cultural events” offered by Lebanon also came to an abrupt end when civil conflict broke out a few years after they arrived.

“People started to tease us that war followed us wherever we went,” she says.

Of all the destinations, Jordan was perhaps Latta’s most rewarding. She revelled in setting a Christmas table for 100 people each of the five years that the family lived in Amman, bringing people together over roast turkey, Brussels sprouts and fruit cake.

It was also a high point for her philanthropic endeavours. She raised funds for the Mental Health Society, helped to build and equip a day centre in the Bakaa refugee camp, and launched the College of Occupational Therapy with the General Union of Voluntary Societies and Al Hussein Society for the Physically Handicapped, which won a Unesco regional award.

Twenty-five years after exchanging their wedding vows, David took his wife to the UN headquarters in New York, and asked her if she was still happy to be married to him.

“Because there were times when I felt a little like baggage moved around,” she says. “I had not done what I set out to do but there were other ways to make an impact indirectly.”

But across three decades that spanned the premierships of Harold Wilson to Tony Blair, she helped her husband make friends for Britain, often over Tunisian dishes, including couscous, deep-fried pastries and, appropriately enough, a pureed carrot salad called omek houria.

“It translates as Your Mother is a Mermaid,” she explains. “Because she prepares this simple thing and yet it is a mind-blowing experience. She can do anything.”

Latta’s list of lifetime accomplishments seems endless. Many, including the ingenuity employed to have several volumes of her grandfather’s poetry and a play published, are chronicled in the autobiography she wrote as a gift to her sons, Nick and Rafiq, and grandchildren.

For so-called retirement, David convinced her to embark on one more move to the continent, where they settled in Alcossebre on the Costa del Azahar, surrounded by the sea, vegetable fields and fruit orchards.

There, Latta added Spanish and the local dialect of Valencian to the eight other languages she has mastered, learnt Flamenco, contributed monthly columns to a newspaper, founded a political party, and channelled “the bull inside” to win a court battle for the provision of drinkable water.

After twinning the village with the commune of Forcalquier in Provence, she continues to organise music concerts, fashion and folklore shows, Sevillian dances, sporting events and other activities.

When it’s pointed out that it might have been difficult to achieve any let alone all of these things had her own career ambitions taken priority over marriage, Latta barely pauses.

“No, I might perhaps have become an ambassador for my country but that work would have been in just one area: diplomatic.

“It’s like the difference between building the Eiffel Tower or building a village with a farm and a school.

“It encompasses a global rainbow of friends from east to west, north to south; all the lovely people with whom we’ve spent memorable time around a table laden with hearty, healthy food.”

That’s how Latta says she would like to be remembered: as the woman who made more friends than she can count.

‘The Tunisia Cookbook: Healthy Red Cuisine from Carthage to Kairouan’ (Nomad Publishing, £25), by Hafida Latta, is available now in hardback