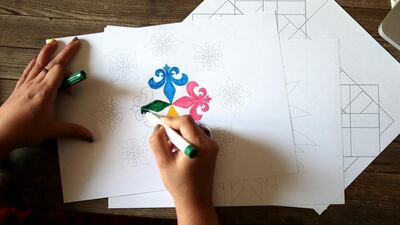

Colouring books for grown-ups have become a bona fide lifestyle craze. They claim to offer a way to combat stress, unleash our creative spirit and generally take time out from our tech-frazzled, gadget-obsessed lives.

But for the makers of crayons and colour pencils, the trend also poses a fundamental strategic question: is this boom in demand just a passing fad or a sustainable trend?

“I dream about crayons at night,” says Andreas Martin, who manages a Staedtler factory in Nuremberg, Germany.

Staedtler is a small, family-run firm with a workforce of about 2,000 people, which has experienced soaring demand, more or less overnight, for some of its coloured pencils.

“These are models we’ve been making for years, and demand always chugged along unspectacularly,” Martin says. “But then, all of a sudden, we weren’t able to manufacture enough. It’s incredible.”

Behind him, a machine spits out yellow-ink pens at a rate of about 6,000 an hour. Another is currently programmed to produce orange ones.

On the floor below, finished crayons in a kaleidoscope of colours are packed into boxes of 20 or 36 for shipping to the United States, Britain or South Korea. These are the countries at the centre of the adult-colouring craze, according to Staedtler chief, Axel Marx.

Colouring books regularly feature among the top 20 best-selling products on Amazon.

“We’re seeing a similar development in European countries, too,” says Horst Brinkmann, head of marketing and sales at rival Schwan-Stabilo, which makes fluorescent marker pens and coloured pencils.

All of the players in the sector are keen to get a slice of the cake. Stabilo has launched a set of crayons and books with a spring motif. Upmarket Swiss manufacturer Caran d’Ache has published a colouring book of Alpine scenes.

Without revealing any figures, Brinkmann says Stabilo’s crayon sales have risen by more than 10 per cent, while the colouring craze helped Staedtler boost sales by 14 per cent last year to €322 million (Dh1.3 billion). “That’s remarkable, in this age of digitalisation,” says Marx.

But the hype also represents something of a headache for factory chief Martin.

“No one knows how long it will last,” he admits.

“We need to strike a balance” when deciding how much to sensibly invest to be able to ride the wave, while keeping in mind that the trend could vanish as quickly as it started, he says.

They are also making use of adjustable working hours, adding shifts at night or on Saturday mornings, he adds. In addition to the 350 regular employees, the factory has taken on approximately 30 temporary workers. But ultimately, the big decision is whether to invest €300,000 (Dh1.2m) for a new machine.

Staedtler is ready to stump up the cash, with the rationale that “if the market falls again, we can use the machines for different types of products”, says Martin.

Others are betting on the durability of the new trend.

At Caran d’Ache, “we have invested in production equipment and extended working hours”, says president Carole Hubscher.

The company sets great store in being a “Swiss-made” brand and “there is no question of relocating to boost production”, she says. Hubscher is convinced that writing and drawing “won’t disappear” and “our growth targets are not solely built on trends”.

Stabilo’s Brinkmann insists that the popularity of adult colouring books “is part of a fundamental and universal trend towards slowing down”.

Nevertheless, “it’s important to continue to innovate in this area” to maintain market momentum, he says, pointing to the new “fashion within a fashion” of “Zentangling” or drawing images using structured patterns.

Staedtler chief Marx is more fatalistic, saying that a trend such as colouring in for grown-ups is fundamentally unpredictable. “But we’re keeping our fingers crossed that it’ll continue,” he says.

artslife@thenational.ae