It was President Franklin D Roosevelt who said: “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself – nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror”. Walking along an orange sandstone precipice, my fears are much more clearly defined: crushed vertebrae, a fractured eye socket, dislocated elbows. A fall from this precarious cliff edge may result in all of those awful things. Despite knowing this, though, and the express route off Jebel Rum being right there, I feel strangely serene.

It is hard to imagine a more dramatic, Martian place to have an accident.

The highest peak in the Wadi Rum Protected Area, and the second-highest mountain in Jordan, Jebel Rum is an enormous sandstone peak rising 1,734 metres out of the red desert. Traversing it will take about nine hours in total, and will require a combination of scrambling, climbing, trekking and, finally, rappelling down the other side. Altogether, this constitutes mountaineering, something I hadn’t tried before this strange day in the Hashemite Kingdom.

But the calmness I am feeling comes from good preparation. In the week building up to this final challenge, I had spent time with Jordanians around the country learning skills that will ultimately make conquering Jebel Rum possible. Had we done things in a different order, I would have been paralysed with fear, but now I can walk along a cliff edge with confidence. The Spider-Man-like grip I seem to have gained definitely helps.

This astonishing landscape was once under the sea, and the sandstone peaks provide such tremendous hold that it feels as though I can walk up almost vertical slopes. It also means that when we take a break more than a kilometre into the sky, sitting inside a small cave, I find what looks like an ancient seashell.

Most people visiting Wadi Rum don’t make the considerable effort to climb its eponymous mountain, instead preferring to stay on the valley floor. But this kind of adventure is getting more and more popular across Jordan, from rock climbing to caving to canyoning to mountaineering. It is become so popular that the Jordan Tourism Board has set up a new arm to promote adventure tourism.

Ahmad Banihani has been employed by this new department, and is by my side as we tour the country, trying what are for me a series of new, daring experiences. For Banihani, this is the sort of thing he does in his spare time, too – he has climbed mountains four times the height of Jebel Rum. Keenly aware of his experience, I find myself putting a brave face on where, if left to my own devices, I might have given in.

We started six days ago, near an unnamed cave somewhere in the northern Ajloun region. Famed for its mighty 1,000-year-old castle, this area has been the site of human settlement for millennia, but for all the millions of people who have passed through here over the years, very few have made it to the bottom of that particular cave.

Finding the entrance isn’t easy. As we stumble around the desiccated landscape, past pomegranate and fig trees, crushing dead sage and snapping dry twigs like old bones, there is an ambient noise of crickets humming in the hot afternoon. After a time, it becomes clear that my guides aren’t entirely sure where we were going. That is part of the problem with virgin sites and new branches of tourism – no signposts.

And we aren’t looking for a yawning cave entrance in a cliff-face, but rather a small, seemingly innocuous hole in the ground. It may have only been a couple of metres in diameter, but it leads to a 30-metre drop into the underworld. Relieved to find it (and more so not to have fallen in), the guides mark the GPS co-ordinates and begin to attach ropes to a nearby tree. Moments later, I am introduced into the subterranean world of caving, also known as spelunking.

The appeal lies in how unlikely it is – how few human eyes have ever laid eyes on the strange underworld. After my guides get to the cave-floor, one lights a sulphur-flame head torch, and we make our way over the uneven ground, gazing at moist stalactites that have never seen the light of day.

The following day is like a negative version of that first experience. Instead of moving in the dark, I am out in the brilliant sunshine, and instead of being lowered down, I am to climb up.

Like caving, rock climbing is something that I had never done before. Coincidentally, however, my younger brother has – he used to be an instructor at his university’s climbing wall. I text him frantically for advice and he quickly replies to tell me to look up and keep my hips close to the wall. The theory sounds incredibly simple.

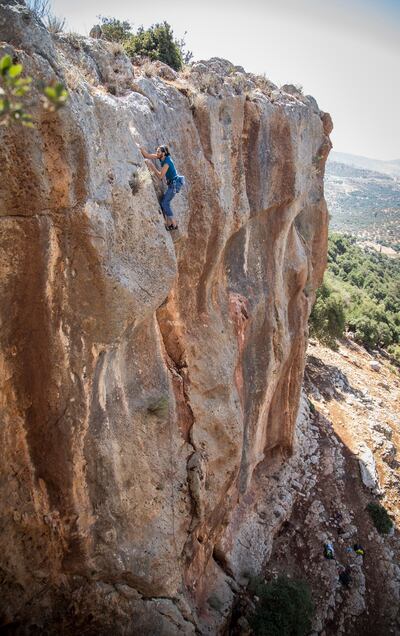

The problem is that I am not faced with a smooth, man-made climbing wall with neat hand-holds – ahead of me is a peach-coloured cliff, with little more than a thin rope leading up through loops drilled into its rough face by expert climbers a long time ago. Expert climbers such as Abood Al-Dabbas, demonstrating what I assume is the perfect technique. I watch from ground level as his long, sinuous limbs consistently find their way up, up, up. I have seen spiders struggle more than he did.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it is a good deal slower for me. And no matter how close I keep my hips to the surface, the whole thing feels incredible unnatural. More than once, I consider giving up; more than once I find a way to keep climbing. Eventually, however, I get to an impasse, my arms and legs quivering with fatigue. It isn’t that I am worried about falling, but that I simply can’t work out how to proceed. I slowly slide back down the rope, defeated, but determined not to let it happen again.

The third of my trials is canyoning, a multi-discipline pursuit in a wadi several hours’ drive to the south. We are dropped off in what seemed like a random spot, high above a deep canyon. Before we set off on foot, I am given a life-jacket and a helmet. I can’t help but think that they are a little unnecessary – especially as the sun makes them uncomfortably hot to wear.

It is at least reassuring that my guides, Abdullah Al Saheb and Sanad Al Hawamdeh, are also wearing them. Which is to say: I am at least confident that they aren’t babying me through the process. After 20 minutes or so of trekking, it quickly becomes clear why we have taken precautions.

Canyoning is a combination of trekking and scrambling, but also abseiling and, frequently, swimming. You start upstream in a wadi – in this case Wadi Balou, part of the humungous Wadi Mujib network – and you move down any which way you can.

Our trip is to last about three hours and requires descending four waterfalls. From our start point, I look down the steep valley, the edges of which have been sculpted by rivulets, giving the impression of geological wrinkles. The nearest sea to here might be famously dead, but water is vitally important – the anorexic stream that runs though Wadi Balou’ has, over centuries, made this madcap trip possible.

Having already used ropes while caving and rock-climbing, I step over the slippery edge with much more confidence, despite the cold water making footing a little slippery. When I finally get to the bottom, I let go and splash into the pool, its coolness shocking the breath out of me. The guides then tell me to swim to shore and wait for them as they take the same way down. Then we gather the equipment and push through the wadi, soggy footsteps drying quickly on the yellow rocks beneath our feet. Unlike in the previous trials, now I can enjoy the changing scenery, as well as let go of some of my fears.

The next day, the drive south to Wadi Rum takes several hours. While the activities I am pursuing are all quite new in Jordan, this tourist route – from Amman to the Dead Sea to Wadi Rum, and the rose-red landscapes of the south – is one of the most well-worn in the country. Banihani and his colleagues are trying to get visitors to their remarkable country to experience it – and literally feel it – in a different way. This morning, my final morning, begins at the bottom of Jebel Rum, with a relentless half- hour of high hiking. No plateaus, no breaks, just marching up towards the astonishing ochre mountain.

My legs quiver and I can hear by heartbeat in my ears, but over that, I hear Banihani say: “Come on, the first 100 years of your life are the hardest …” He had said this during each of my activities through the week. I’m not entirely sure what he means, but I put my head down, take a deep breath and push on again.

_____________

Read more:

Flydubai launches new routes to Jordan and Greece

Something for everyone: best ski resorts for groups

Top 10 Middle East holiday swaps - in pictures

_____________