Covered in dents and with its black paint peeling off, the timeworn sewing machine has seen better days. This bulky steel contraption weighs more than 30 kilograms and uses an old-fashioned treadle system similar to those in the early sewing machines from the 1800s. Every day it is in motion. Yet it has not moved from this spot in more than 80 years. In that time, the machine has produced tens of thousands of songkoks, a velvet Islamic hat similar to a Turkish fez that is worn by Malaysian males during formal events, religious ceremonies and festivities. Each has been made by hand by members of one family here in Georgetown, Penang.

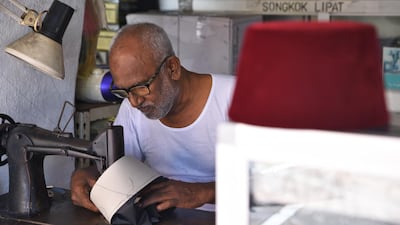

As he leans down, carefully stitching a songkok, I ask Haja Mohideen, 72, if he ever thought about getting a new sewing machine. He stops his work and peers at me through his thick, black-rimmed glasses. With a furrowed brow, his reply is short and pointed: “Why would I want to do that?”

Mohideen has no interest in change. Routine and tradition take precedence. Were he keen on modernising or expanding his business, he would have done it years ago. He could have opened a factory and mass-produced cheap songkoks, which is how most of the hats are now made. That would have been far more lucrative. Instead, he chose to honour the attributes that made him admire his father as an artisan – humbleness and precision.

It was his father who started this business in 1936, right here in this cramped workshop in Georgetown's Little India neighbourhood. The store is built into the walls of Nagore Dargah Shariff, Penang's oldest Indian Muslim shrine. This place of worship is on Chulia Street, one of the main thoroughfares of Georgetown, a Unesco World Heritage-listed city famed for its British colonial architecture. The street was named after the Chulias, the term historically used to describe the Tamil Muslim traders from southern India who moved to Georgetown after it was established by the British in the late 1700s.

Mohideen, whose family also came here from southern India, said he understood the songkok had been commonly worn in Malaysia and its neighbouring countries Indonesia and Brunei since well before the Chulias arrived in Penang.

Historians believe the songkok most likely became popular in this region in the 13th century. This coincided with the arrival in Malaysia of Islam, which was introduced by Indian and Arab merchants. At this stage the Strait of Malacca – the ocean passage between the Malay Peninsula and Indonesia – was a key path on the trading routes that connected China with India and the Middle East. Islamic merchants from India are believed to have brought with them a hat resembling the songkok.

Over the centuries, it became the main form of ceremonial headgear worn by Muslim men in Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia, where it is also known as a peci. In those countries, the songkok is commonly worn not only by ordinary citizens but also by high-profile figures such as politicians and military leaders.

In Brunei it is even part of the official uniforms of the country's armed forces, police and fire fighters. Nowadays in Malaysia it is most commonly worn during Ramadan.

It is in the lead up to Ramadan that Mohideen is busiest. Typically he receives up to 700 orders for songkoks in the two months prior to the holy month. Given that each hat takes him up to two hours to complete, it is during this period that he is especially thankful for the help of his son-in-law, Abdul Kader.

Mohideen when he made his first songkok 60 years ago, took over the business after his father died in 1973. For a long time after that, he struggled due to a lack of assistance. He had also worried that, with mass-produced songkoks becoming more common, his craft would one day die out in Penang.

Fortunately, Kader came into his life and became his apprentice. Together they are the last full-time handmade songkok artisans on the island. Their work is labour-intensive. At the most frenetic times of year, the pair sit together for up to 12 hours a day and seven days a week inside their workshop, which opens out on to the street, exposing them to Penang’s oppressive heat and humidity. But there is also an upside to the design of their studio, Mohideen tells me. “Many people walk by saying hello and talking to us [so] we feel part of a community,” he says.

Most of the time, however, he and his son-in-law are deep in concentration. Making a beautiful songok is complicated. They start by creating a frame for the hats from more than a dozen layers of newspaper, which is then stitched together with cotton. Based on the head measurements of his customer, he uses a knife to cut an oval shape for the top of the hat, and a longer, thinner section that wraps around to form the walls of the songkok. These two parts are then sewed together, ready to be covered in velvet and prepared for the insertion and stitching of a second velvet covering on the inside of the cap.

When made by hand in this manner, no two songkoks are identical, Mohideen tells me. This is what makes them special. On a good day he and Kader together can make up to 15 songkoks. The traditional colour for the headgear is black, but the pair also make the hats in navy blue, maroon, purple, green and brown if a customer chooses. Buyers can also request a particular height of the hat, and the level of decorative detail they want inside it. Despite the amount of work that goes into each one, Mohideen charges only between Dh20 and Dh35 for each.

“Money is not so important,” he tells me. “What we do is more important. We make special things for people.”