Gazing through a tall open gateway, I watch a group of pilgrims stroll closer along a broad "street" lined with ancient colonnades. They pause briefly in the shadows before gliding past in white robes and vivid saris. As their voices fade away into the stillness, I'm once more left alone. Here in Hampi, only solitude marks the porous frontier between the flamboyant past and an eerie present.

In headier days, Hampi was called Vijayanagar, or City of Victory. For about two centuries until 1565, it was the capital of a huge empire that dominated south India from its western to eastern seaboards. The thriving city was large – about 40 square kilometres – and notably prosperous. Several kings enhanced its considerable prestige by constructing grandiose temples, enclosures, pavilions and barracks. Foreign traders and adventurers were impressed and awed.

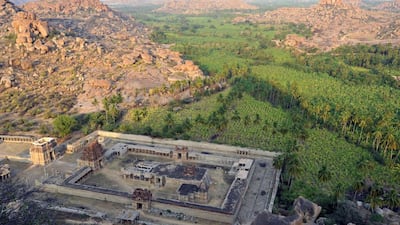

Today, it’s hard to think of another sight in India this significant yet still relatively little-known or visited. Although Hampi became a Unesco World Heritage Site in 1986, tourism hardly noticed. Rolling up here in 1989, I marvelled at Hampi’s curious emptiness and picturesque setting. Watered by the meandering Tungabhadra River, Hampi’s ruins stand amid low granite hills and outcrops dotted with surreal, house-sized boulders. Between them stretch dense plots of banana trees and sugar cane still cultivated by local villagers. It’s a landscape further softened and greened during the monsoon.

Hampi’s relative obscurity may soon change. Last summer, upmarket Indian hotel group Orange County opened Orange County Hampi, an impressive, low-rise, five-star property set in 11 hectares of tranquil Karnataka countryside about seven kilometres from the site. Not only is there nothing else like it near Hampi, but it’s also a first for northern Karnataka (its southern half, mainly the state capital Bangalore and Mysore, boast the upscale properties).

“Yes, I suppose you could say it’s a bold move,” admits Abhishek Dhar, Orange County Hampi’s manager, to me over breakfast one morning. “But more regional properties like this would be welcome. They’d help develop a tourist circuit.”

Karnataka has long been overlooked by tourists drawn to better-known, better-marketed, states such as neighbouring Goa, Kerala and Tamil Nadu. But during a week there, I discover that northern Karnataka’s attractions hold their own.

Hampi easily tops the list. Divided into the so-called Royal Centre and Sacred Centre, most of its principal sights – such as the Elephant Stables, Queen’s Bath, Lotus Mahal and several monumental temples with their own walled enclosures – can be reached by a network of narrow, uncongested roads. In a nod to environmental concerns, one area even has electric carts.

Yet Hampi’s real pleasure lies in visiting the highlights and exploring its nooks and crannies on foot. I begin by the huge Virupaksha Temple, still an active place of worship and focus of most visitors’ attention, before heading towards the Tungabhadra. By the time I reach the King’s Balance (a simple granite archway where each year the king was weighed against gold and jewels that were distributed among “high-class” citizens), there’s hardly a soul about.

Several now-disused temples recall the monuments of Angkor in Cambodia and boast long “driveways” flanked by colonnaded structures. Yet the only vehicles ever brought here were huge wooden ceremonial chariots that, anointed with presiding deities for annual festivals, were dragged and paraded by crowds of fervent devotees, some of whom willingly died under their massive wheels.

Later, I clamber up towards a stretch of masonry wall that snakes across a low, boulder-strewn ridge. Enigmatic part-ruined lookouts and outbuildings stand here and there, their pillars leaning at jaunty angles from ranks of undressed stone. It’s from spots like this (particularly the precipitous Matanga Hill, which is the best sunset vantage point) that you will get the most satisfying sense of the city’s scale and complexity.

Vijaynagar’s demise was swift. To the north, previously fractious kingdoms – the Deccan Sultanates – joined forces and attacked their main rival in 1565, spending months sacking the capital. The fruits of some of their booty can be seen in Bijapur, almost 200km north, but I break my journey in Badami, a small country town on the edge of an artificial lake.

First impressions suggest a workaday place, but behind the old quarter’s knot of lanes and alleys lies Agasthya Lake, framed by an amphitheatre of sandstone cliffs. This was the Chalukya dynasty’s sixth-century capital. I climb a path up through a maze of fortified ravines to the citadel’s summit. Apart from walls and squat bastions, its remains are scanty, but the views make it worthwhile. Across the lake on the opposite cliff nestle a series of rock-cut caves – shrines – with pillared porches, dim halls and recessed sanctums. Elaborately sculpted deities gaze on mutely, the exuberant carving belying the centuries since their conception.

Yet the Chalukya masons and sculptors saved their best for a handful of sites barely 30 minutes’ drive away. Aihole and Pattadakal – now small, ordinary villages – boast some of south India’s finest ancient temples. If pushed for time, Pattadakal (also a World Heritage Site) is the one to visit. Set in neat, manicured gardens, its clustered temples showcase extravagant ornamentation and bas-reliefs with particularly moody interiors amplified by the interplay of diffused light and soft shadows.

I head on to Bijapur, probably the best known of the Deccan Sultanate capitals. Guides tend to over-egg its “Agra of the South” epithet, though the Gol Gumbaz mausoleum, its most famous monument, does substitute sheer impressive mass for the Taj Mahal’s elegance and beauty.

Construction of Sultan Mohammed Adil Shah’s tomb began almost as soon as he ascended the throne in 1627. Essentially a giant cube topped with a massive hemispherical dome (said to be slightly smaller than St Peter’s in Rome), it remains one of south India’s architectural landmarks and is fully accessible to visitors.

After climbing the narrow, winding staircase in one of its minar-like towers, short, tiny passages lead from a lofty terrace through the dome’s base into a vast interior gallery. Although famed for its acoustics, amid visitors’ whooping and screeching, you will be lucky to appreciate them. I wait patiently, my ear close to the wall, and catch snatches of words and conversations relayed in a curious, disembodied echo.

Far more tranquil (apart from watchmen occasionally scolding almost-courting young couples) is Ibrahim Rauza, the elegant tomb of another Bijapur sultan. Together with its facing and now disused mosque, this beautiful ensemble stands in quiet gardens on the edge of town. Dainty onion domes framed with slender turrets and minars crown facades embellished with fine geometric designs, including unique jali, or stone-lattice screens, carved with Quranic inscriptions.

Strolling this compound, I reflect that this part of Karnataka neatly distils elements of Hinduism and Islam, the twin strands of India’s cultural DNA.

travel@thenational.ae