It's a two-and-a-half-hour drive from Baku to Qabala, which is no sweat in the back of a Mercedes-Benz S-Class, the car sent to collect me. As we weave through the capital's heavily industrial outskirts and reach the M4 motorway, which skims around some spectacular high plains before reaching the mountains, the smell of stale cigarette smoke is an ironic prelude to a detox programme.

Feeling slightly nauseous and to my driver’s bafflement, I keep having to open the window for fresh air. Endearingly, along sections of the route, men stationed by the side of the road become animated as we approach, thrusting bunches of flowers towards us, hoping to sell them. We stop only at a “luxury” local restaurant to use the bathrooms; the food looks and smells divine but the toilets are the opposite.

It's too bad that I didn't eat, because I arrive at the Chenot Palace just after the hotel's only restaurant has finished serving lunch. The hotel is set in pleasant semi-rural, lightly forested surroundings beside a lake, but while it has good-sized grounds, most of the area around it is private property, and so out of bounds. So it's a relief that this is a destination spa and a world unto itself.

The property

Still, while the 72-room property is slick, beautiful and very expensively furnished, I had been worried about the food. The hotel had been reluctant to provide menus in advance, saying it depended on my programme, and a friend who stayed at the original Espace Henri Chenot – Palace Merano in the Italian Dolomites a few years ago told me that the general manager there had delightedly told her how much cheaper it was to run a spa than a regular hotel, because instead of having to have bar staff on duty until 4am and lobster and steak on standby, they had everyone in bed by 9pm and salad on the menu. “It was full of older men and very beautiful depressed-looking Russian girls,” my friend told me of the Italian spa. “Plus when I told the Italian doctor I had about 10 cups of tea a day, she asked, aghast, ‘with milk?’ – and looked about to throw up when I said yes.”

I’m thus not surprised that the only thing on the menu on the afternoon of my arrival is a medical consultation.

No welcome drink, no massage, not even a basket of fruit in the room. Yet that's the point. So much of what we consume is unconscious and unnecessary, a reaction to stress, boredom or simply pure laziness and gluttony. We stuff ourselves because we can, and if we lead sedentary lives, we pay for it later, in terms of the cost to our health – and to our wallets, if we have to check into places like this. It's this cycle of imbalance and inflammation that Chenot spas aim to treat, and it's this sense of genuine caring, rather than the saccharine sweetness I experience in most hotels, that is immediately apparent.

After a pot of herbal tea in the smartly presented restaurant, a waiter approaches me with menus for tonight's dinner and tomorrow's lunch. Each are three courses, and there's a choice of starter and main.

Initial consultation

The hotel's state-of-the-art medical centre is attached to the spa, on the lower ground floor. The hyper-modern space is white, calming and not too clinical, staffed with a top-class team

of European doctors. My consultation is with Italian Dr Claudio Tavera, a sports medicine specialist. Dr Tavera explains that the clinic's aim is to "deliver wellness" through the "optimisation" of one's own health according to the lifestyle we lead and how it is affecting us – including eating, moving and managing stress. Then, the plan is to "stimulate the body to react, restrict calories and increase the alkaline potential".

Dr Tavera is mildly concerned about the health effects of me living in the Gulf for so long, saying I have a genetic predisposition to living in cold climates and certainly not so close to the equator. When I explain that I travel a lot, he notes that this places even more stress on the system. It’s not judgemental – merely factual observation signalling a holistic approach. I point out that he’s a Sardinian living in the cold mountains of Azerbaijan, and he smiles, saying it’s at least dry cold, rather than damp.

The doctor checks my blood pressure and breathing, and reviews my medical history and goals. I want to lose at least five kilograms, but there's a limit to what can be achieved in a few days, so we mostly discuss my current fitness regime. I'm surprised and delighted to find that we agree fundamentally. Since giving up expensive and time-consuming group fitness classes last year, I've taken to training myself in the gym for 20 minutes a day before work. I've lost more weight and feel better than travelling half an hour each way to a class and slogging my way through 60 minutes of pre-set routines. "This

is the best way," Dr Tavera says. "Twenty minutes of interval training three times a week is absolutely optimal and enough."

Because I still need to lose weight, after warming up, I should run for two minutes at a speed that challenges me (that is, I should be out of breath) before slowing to a fast-paced walk for two minutes, then push the speed back up, and so on for a total of 20 minutes maximum. I'm pleased that further drastic measures aren't needed, though Dr Tavera warns me against doing nothing, because neglect at my age "can reach a point where it's very difficult to do anything about it".

Going on a vegan detox

Thus I proceed with a three-day vegan “detox” programme in which my food is reduced to 900 calories per day, down from the 1,435 I would need if I did no exercise and maintained the status quo. Alcohol and caffeine is banned, but like the other (mostly Russian) guests who want results, I choose to obediently follow the rules for my own benefit, rather than feeling like I’m being deprived. This runs alongside an almost full-time programme consisting of advanced medical testing in the morning, combined with afternoons of hydrojet baths and “energetic massage”.

Dinner that night is served at 7pm, and my table, beside the window, is mine for the whole stay. On it are three large bottles of water, one plain and the others laced with vinegar and lemon juice. Within a couple of minutes of sitting down, a small broccoli soup with chilli arrives, followed by tofu with vegetables and a herbal tea or chicory coffee. I have both and am surprised at how good the “coffee” is. I’m also surprised by my lack of cravings for other food, and thanks to the swiftness of the meal, have time to move to the next-door lounge-library to do some work before bed.

___________________

Read more:

Hotel Insider: The Retreat Palm Dubai MGallery by Sofitel

Getting away from it all at Ras Al Khaimah's Alma Retreat

My stay at a Dh60,000 a week Swiss spa

___________________

Despite feeling very tired, I don't sleep well because the air conditioning does not reduce the room to the required temperature, so I have to open a window, meaning that I can't use the blackout shutters and the room is lit by the powerful floodlights shining onto the front of the hotel. It's a shame, because the room itself is extremely comfortable and well-designed, and has a view of the lake from the balcony.

In my frazzled state, breakfast the next morning is a shock. There’s no menu, and my only choice is, again, herbal tea or barley coffee, and this is accompanied by a small bowl of fruit puree, which I query. Yes, that’s really it.

Bioenergetic screening session

The extraordinary thing is that again, after this breakfast, I'm not hungry. What's more, because I'm not overly full, there's no need to sit around waiting for the food to digest before starting my activities. I head to the pool for a swim before the first of the day's consultations starts at 9am. The first of these is a "bio-energetic screening" session which looks at the body's "vital functions" through resonance analysis technology.

According to Dr Evangelos Sofikitis, who administers the test and is an expert in evidence-based alternative medicine, the machine computerises thousands of years of Chinese medicine and, for the clinic, feeds into a belief in homotoxicology, which views the cause of disease as an accumulation of toxins. “If we have stagnation, energy doesn’t go properly to the organs,” he says.

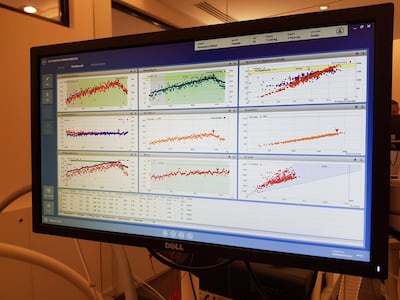

I hold two metal prongs connected to a machine that is said to detect imbalances and stresses in 35 different areas, from the adrenal glands to the liver, lungs and heart. After holding the machine for a few minutes, a report is printed, suggesting that while most of my functions are "normal", my eyes, digestion, liver and sinuses are "weakened" and my brain's hypothalamus gland, which plays an important controlling role in most of the body's key functions, is "stressed".

Dr Sofikitis says that because I am “sensitive”, I need to “avoid negative people, things, everything” and protect myself from unnecessary stress and drains on my energy. While the advice rings true, I know that I’ll feel much more relaxed after I have a massage, and I wonder if these tests are carried out before you visit the spa so that the perceived benefit at the end is greater.

Getting some results

Next, after filling out a questionnaire, I have a 30-minute nutritional consultation with another Greek doctor, a nutritionist and dietician called Ada Nisianaki. She talks a lot of sense, and remarks positively on my day-to-day eating habits, and even she can relate to the number of hours most working people spend behind a desk. While we can all get up and move around at work more, she also advises restricting the number of further hours spent sitting once one transitions from work to home. Eating light meals at night, avoiding alcohol and television, and committing to team sports are all ways to cut down the frightening total number of hours spent sitting.

Next is the test I've been dreading – a "vascular age assessment", which measures arterial function and the stiffness of the arteries. Since a blood test last year revealed higher than average levels of bad cholesterol, I have wondered how much damage may have been caused over the years by this when combined with an increasingly sedentary lifestyle and having grown up with a mother who smoked. I've also been dreading it because I cringe at anything needle- or vein-related, and am slightly agitated throughout this procedure, which is like an extended blood pressure test and works by measuring the health of the different arteries by mapping the pulse wave reflection returning from the various arteries to the heart.

The doctor assures me that thousands of academic papers have proved the accuracy of this remarkable test, and I’m thrilled to be told that not only do I not have any problems, but that my vascular age is 13 – meaning not that I’m undeveloped, but that my system is supple, efficient, unclogged, undamaged and in about as good condition as someone my age or even much younger could hope to be. Again, the verbal test results are backed up with a full printed report, including an arteriography and cardiovascular risk report.

As if the day couldn’t get any better, the next test, which promises to show “the real age of the body” confirms the previous one. A skin-collagen-thickness assessment uses a small hand-held ultrasound device to assess the thickness of my collagen, that magical substance yearned for by ageing women the world over because it allows skin its strength, elasticity and overall health. The painless test measures two samples of skin from under my arm. This area is chosen, apparently, because it’s relatively undamaged by sun, which strikes me as slightly odd, given that it’s the other, much more visible areas that one is concerned about.

Learning about fitness level

Nevertheless, it's not just outward appearance that should bother us. Collagen, the doctor tells me, is the same substance that our arteries are made from – so when he tells me that my "collagen score" is 66, I nearly fall off my chair. This level of collagen would be high in someone who is 15 to 19 years old. When I later suggest to Dr Tavera that being raised vegetarian may have helped, he tells me it's more likely superior genes. "These things are 25 per cent lifestyle and 75 per cent genetic. You are very lucky," he says. I leave his office feeling happy and determined to look after this gift from my parents and those who went before them.

Next is a test using another revolutionary piece of equipment, a mineral and heavy-metal intoxication analysis using a small laser that confirms almost exactly the results I was given last year at a different spa in Switzerland. "Each material has its own barcode, and it's this that the laser reads", explains the technician.

The day's revelations are broken by a lunch of pear in syrup, a carrot salad with curry and lemon-grass and vegetable "lasagne", followed by herbal tea and, you guessed it, chicory coffee. Then, at 3pm, it's time to crack on with an assessment of my cardiovascular fitness. I'm under no illusions that I will ace this test, because I know I'm horribly unfit. What I want to know, however, is the aerobic threshold I'm reaching when I do exert myself, and the capacity of my lungs. I have wondered, at times, if growing up in an inner city surrounded by smokers has caused mild asthma or other issues.

Wearing a mask over my mouth and a heart-rate monitor, both of which have wires connecting them to various machines, I set off on the treadmill for 20 minutes. While my fitness level is poor, it’s not critical, and I never get into a zone where I’m not taking in enough oxygen relative to the activity, meaning that if I train more, my cardiovascular capacity will improve in tandem. I simply need to move more, and my body will adapt: there are no more excuses to be found.

Time for relaxation

Finally, it's time for some relaxation. "Hydro-aromatherapy" involves lying in a high-tech bathtub in one of three beneficial herbal solutions, being variously pummelled by jets and treated to an ever-changing light show. After 20 minutes, it's into the adjoining room for another 20 minutes spent lying on an inflatable massage bed wrapped in marine algae. After that, I'm hosed down with a high-pressure jet in a tiled wet room by my affable therapist Yegana Hajiismaylova.

Finally, I’m handed over to a brilliant massage therapist called Mubarik, who has the unenviable job over the next few days of crushing the tension out of my rock-hard shoulders and, as he puts it, “removing toxins” from deep within the muscle tissue, using a combination of almost-painful massage and quite-painful suction-cupping. His efforts are monumental, and he says he won’t be satisfied until I have a “soft body like the people in Bali”.

After three days of this, which involves minimal effort on my part, Mubarik’s aim, which seems to be to awaken the “real body” we all have underneath whatever extra we are carrying, has been achieved. My body is both softer and firmer where it needs to be, though barely half a kilo lighter. I leave with a heightened awareness of the unconscious inflammatory cycles of consumption, exercise and stress that we so often find ourselves in, and with a new appreciation of how unhungry you can feel on a detox regime. As I’m told by one of the group of excellent and kind doctors on hand here, “even good food too often can be bad”. It’s simple, powerful stuff. In the place where luxury isn’t more but less, I should have done a full week.