In June 1798, a young and power-hungry French general was nearing the coast of Egypt aboard the flagship Orient.

Not yet 30 years old, Napoleon Bonaparte was a man in a hurry, having risen swiftly through the military ranks during the bloody French Revolution. While his enormous armada, which included some 36,000 soldiers and more than 100 scientists and intellectuals, parted the summer waves of the Mediterranean, Napoleon's heart must have soared as he spied this land once renowned for its pharaohs.

As the first modern Western military incursion into the Arab world, these would-be conquering European interlopers were on their way to making history.

Why Napoleon and why Egypt?

General Napoleon was the leading trailblazer. The future French emperor, born 250 years ago this month, in August 1769, made landfall at Alexandria on July 1, 1798. It would mark the beginning of a three-year campaign that would bear witness to both remarkable success and abject failure – and, ultimately, French expulsion from the region at the hands of the British. Crucially, however, it would also usher in political and cultural changes that would both affect Egypt and lands further afield.

"For political reasons, France's [governing] Directory in 1798 was eager to keep the ambitious and charismatic Napoleon as far from Paris as possible, so they appointed him to lead an invasion of Britain," says Cameron Reilly, a Napoleon enthusiast based in Australia who was awarded the Legion of Merit in France for his contributions to Napoleonic history. The scheming Napoleon, he says, "quickly decided that this was a suicide mission", as the French navy was "still not strong enough to attempt a direct invasion".

But France was determined to be the only European superpower. "Doing nothing to deter Britain from attacking France wasn't an option, so, like a good soldier, Napoleon came up with the best viable alternative," says Reilly.

Adam Zamoyski, author of Napoleon: The Man Behind the Myth, says this alternative came in the shape of "excluding the British and the Russians from the Mediterranean, by making sure that they would find no friendly ports in the East". In other words, the Expedition d'Egypte was intended to disrupt the British Empire in lieu of a full frontal assault against their old enemy. They used Egypt to do this.

An 'unmitigated disaster'

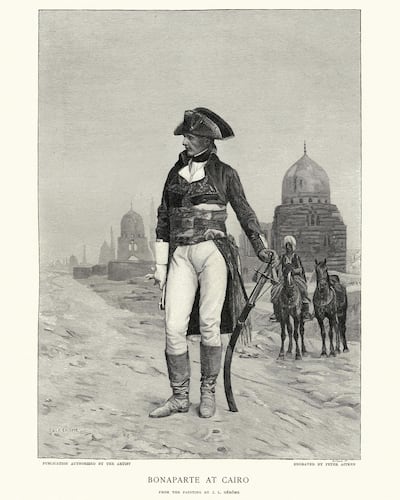

From Alexandria, Napoleon advanced to Cairo. He did so as a self-proclaimed saviour to push out the Mamluks, who were ruling the ancient territory that was then under nominal Ottoman control.

His sophisticated troops proved too much for the Mamluk resistance but, under a burning sun, and in an alien environment, their early campaigning came at great cost.

"They land and have no clear maps, and they don't know what they're doing," says the Oxford professor Michael Broers, author of Napoleon: Soldier of Destiny.

“They’re wandering around the Nile Delta – and the [soldiers] that move up the fertile bits of the delta gorge themselves on melons and dates and get dysentery, while others take a wrong turn and wind up in the desert.”

Despite this, and the heatstroke that also killed and disabled many of Napoleon's campaigners, Broers says the "ramshackle" Mamluk troops were unable to contain a French military dominance that, according to one Napoleonic soldier's recollections, also included some blatant acts of terrorism against the local population. "[We] finished burning the rest of the houses, or rather the huts, so as to provide a terrible object lesson," wrote Sergeant Charles Francois in a discovered diary entry.

On August 1, 1798, however, British admiral Horatio Nelson swept into Egypt and destroyed the French fleet. Yet Napoleon’s real undoing, says Broers, was his subsequent push towards the Levantine coast as the plague and stiff Ottoman resistance made for an “unmitigated disaster”.

What next for emperor and Egypt?

In the late summer of 1799, the native Corsican, closely eyeing power in his restive homeland, deserted his troops and returned to France, where he would stage a coup and come to power as first consul before any public fallout from his developing Egyptian disaster could hamper his ambitions.

France's campaign in the Middle East eventually ended after its expulsion from Egypt by Britain (and the Ottomans) in September 1801. Paul Strathern wrote in Napoleon in Egypt: The Greatest Glory, "between 10,000 and 15,000 Frenchmen were probably killed or died of disease during the occupation of Egypt, as well as many times that number of Muslim warriors and [Mamluks]".

The birth of Egyptology?

But the end of this campaign was not the end of the story – in fact, despite the wanton violence brought to bear by this invasion, it was merely the beginning of a fascination with Egypt.

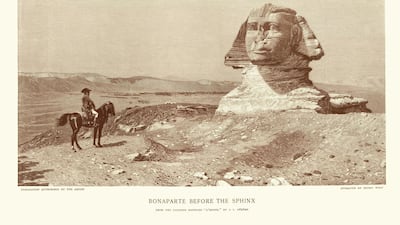

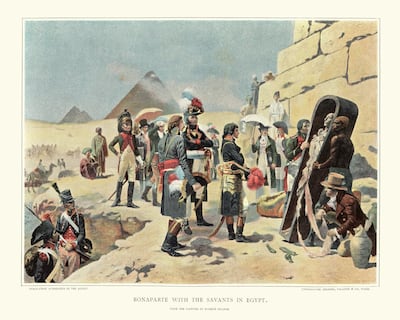

Napoleon had also taken 167 scholars with him to the land of the pharaohsm, after all. The result was the Description de l'Egypte, which, published in volumes between 1809 and 1829, recorded the monuments of ancient and modern Egypt, as well as its flora and fauna.

The Rosetta Stone, which was discovered by French troops in 1799 in a small Nile Delta village and is today housed at the British Museum, also proved critical to deciphering hieroglyphics. Such was the French cultural intervention here that many regard this era as the birth of Egyptology. "The addition of intellectuals to the invasion fleet matched public enthusiasm for exotica," says Professor Peter Hicks, a British historian with the Napoleon Foundation in Paris. "[It] fitted Enlightenment ideals and also corresponded to Napoleon's own romantic idea about the importance of learning and his own romantic image of himself as a modern Alexander the Great. It also acted as a smoke screen to the real strategic aims of the invasion."

In Egypt, the end of the French campaign resulted in Muhammad Ali, a high-ranking Albanian army officer who had fought the French on behalf of the Ottomans, claiming the North African territory for himself as he filled the power vacuum. Ali's role as Egypt's Ottoman governor witnessed the beginnings of a royal dynasty that would last until 1952.

As for the Middle East itself, many observers point to Napoleon’s Egyptian adventure as something of a precursor to future imperial forays here.

Indeed, although Napoleon’s own interest in Islam and Islamic culture was thoughtful and genuine, says Zamoyski, “the underlying arrogance and the assumption that [the French] had understood the Islamic world and the mentality of the peoples of the region lay at the root of all European ventures in the region throughout the 19th and 20th centuries”.

That overconfidence is not unique to the Europeans, either – take American president George W Bush's 2003 invasion of Iraq, when, like Napoleon, he promised to liberate the very land his 21st-century troops would come to occupy. As Napoleonic author Juan Cole wrote in 2007: "For both Bush and Bonaparte, the genteel diction of liberation, rights and prosperity served to obscure or justify a major invasion and occupation of a Middle Eastern land, involving the unleashing of slaughter and terror against its people."

These events may be separated by more than 200 years, but plus ca change in the murky world of aggressive Western-led interventions.