Behind the 20 young debutantes who are invited to Paris's Le Bal gala every year are a pride of famous parents, a froth of haute couture designers and one hand-picked jeweller. This year, Mumbai diamantaire Harakh Mehta custom-created the jewels worn by each young "deb" last month, including American heiress Kayla Rockefeller; Chinese actor Jet Li's daughter Jane; Bollywood actor Sanjay Kapoor's daughter Shanaya; Spanish musician Julio Iglesias's twins; Jimmy Choo co-founder Tamara Mellon's daughter Araminta; and a few European princesses.

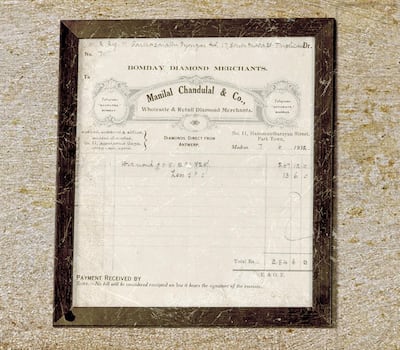

"I had been following the Le Bal event for a number of years. After expressing my interest to its chief executive [Ophelie Renouard], I went to Paris, and made a presentation of Harakh's workmanship," says Mehta, who hails from Palanpur's age-old jewellery community and is a fourth-generation diamond merchant – his family runs Bombay Jewellery Manufacturers, while his great-grandfather set up a gemstone sourcing business

in Antwerp.

Mehta’s own company, Harakh, creates haute joallierie pieces for discerning luxury seekers from all over the world. “I was also keen to get involved with Le Bal because most of Harakh’s current clients are the age of these girls’ mothers, and at some point, I felt we were missing the voice of the youth,” he adds candidly. “I wanted to better understand the preferences of millennials and Gen Z, and how they perceive jewellery.”

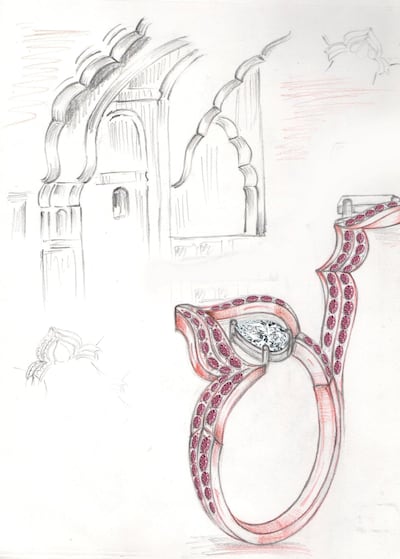

Accordingly, Mehta spoke to each of the women two months before the event, and then began furiously sketching and designing a 100-piece collection of earrings, necklaces, bangles, rings and tiaras, worth about $10 million (Dh36.7m). Of course, bespoke pieces are part of the ethos at Harakh, which has a dedicated team of 15 karigars (artisans) working on its one-off commissions and in-house collections.

"When I started the company, I selected only one or two craftsmen from the [family's] team of 500, those who I believed had not only the potential to create high-end jewellery, but also the mindset to achieve the level of quality to stand shoulder to shoulder with the best in the world," he says. "Then I interviewed a man whose mum's father was one of Bengal's most famous karigars, and I realised the skills and genes passed down over the generations is an important trait in this field. I am proud of my karigars; they have magic in their hands and feel the joy of creation."

Joy is what Harakh means, and is a quality Mehta imbues in all his collections, which he says "have some link to a moment of happiness I felt, especially in my childhood". The Cascade line, for instance, is a celebration of the Mehta family's road trips to Lonavala when they would make pit stops to bathe in the waterfalls gushing down the Ghats on the way to the hill station. The Ghungroo collection, meanwhile, is an ode to Mehta's 5-year-old daughter, who was "wild with joy" upon being awarded her first pair of ghungroos (anklets) by her Kathak dance teacher.

Alongside, buyers get a reflection card with each piece, “where I share the journey of how I created the collection it belongs to, albeit through a spiritual lens. For Ghungroo, for example, it’s patience because Kathak is a dance that needs an infinite amount of discipline,” Mehta explains.

The diamantaire is also particular about the quality of his gemstones, which range from rare natural pink diamonds from Australian mines to pure, untinted D-E-F white diamonds. "Recently, I came across some beautiful coloured stones on a trip to Jaipur, which are relatively untapped in high jewellery, so I'm looking forward to doing a collection around those. With diamonds, I prefer to source the stones myself, even for bespoke commissions, as I am very exacting about the colour, cut and clarity of diamonds I work with," he says.

For all of that, Mehta is refreshingly open-minded about laboratory-grown diamonds, which many luxury jewellers are quick to dismiss outright. “They are the best possible replacement of mined diamonds, they are very important and have a place in the market,” is this diamond merchant’s take. “Kudos to the advent in technology that is able to create something so similar to what Mother Nature does; and to the labs that can identify the differences between the two. Such diamonds are a great alternative for people who want to own something as close to a mined diamond, to adorn themselves with it.”

To this, however, he adds two caveats. One, that jewellery is about emotion and a lab-grown diamond needs to come with full disclosure and proper identification out of respect to its buyer and wearer. And two, Mehta believes that while the “growing” process rules out the issue of blood diamonds, it is not necessarily ethical. “Immense energy is required to create these diamonds. You’re not digging into the Earth, but the electricity generated could light up hundreds of Indian villages. As they say, the most sustainable piece of clothing is already in your wardrobe or, in this case, the diamond that already exists.”