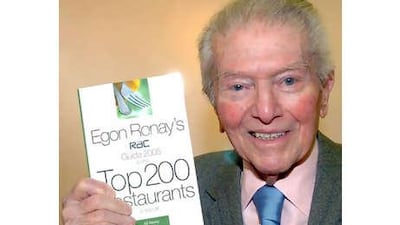

It's quite something to think of the steely influence that Egon Ronay exerted on the British food scene, given that he arrived in the country in 1946 as an impoverished war refugee from Budapest. But Ronay, who died last weekend aged 94, was perhaps always destined for a career in a pocket of the food industry. Before the war, his father was a wealthy Hungarian with five restaurants in the capital city. Post-war and Russian occupation, he decided to leave. Upon arrival in London, he was put to work in a restaurant called Princes in Piccadilly by a friend of his father's.

It was this early acquaintance with British dining habits that so repulsed him. Legend has it, when buying a cup of tea at Victoria station, he asked for a teaspoon, and was directed to a single, communal spoon twirling from the ceiling on a piece of string. For the young Ronay, this would simply not do. By 1952, he had raised £4,000 (Dh21,500) and set up Marquee, his own French restaurant near Harrods. The food writer Fanny Craddock visited and declared it the "most food-perfect" restaurant in London at the time; her Daily Telegraph editor visited shortly afterwards. Ronay's weekly food column in the paper began thereafter, as did the idea for a guide.

His wasn't the first of the popular modern food guides.The Michelin Guide had existed since the beginning of the century in France, a project originally started by a pair of French brothers, André and Edouard Michelin. The duo, who manufactured tyres, wanted to make sure that French motorists could find a decent place to bed down and eat while on the road. The star system was introduced in 1926 and expansion across Europe followed.

Ronay completed his first, British guide in 1957. The costs were met through the sale of advertising space to Ford; his material came from rattling around the country in his car with one other inspector and eating up to four meals a day. It was an instant hit on release, and spawned a subsequent, annual guide. This was always written from scratch, Ronay having hired a team of inspectors to visit restaurants across the UK who were expected to behave as anonymously as a troop of government agents. He never accepted so much as a free drink in his stringent efforts for impartiality, and was scornful of other guides.

The Michelin Guide was for snobs, Ronay said, and the Good Food Guide for those with insufficient food expertise. His own book rights were sold to the AA in 1985, before being sold on again several years later, after the motoring organisation found itself in financial trouble and being bought back by their creator in 1996. Ronay's insistence on a cloak and dagger approach to reviewing, however, will remain part of his legacy to the food scene and specifically with regards to the impartiality of guides. Which are the ones to trust among those that are essentially glorified advertisements?

The Michelin Guide is the most revered, its stars the most sought-after. It has now spawned itself across Europe, in America and Japan, but remains strictly anonymous with a vast team of inspectors split into regions and who visit destinations unannounced. Its inspectors have never been allowed to out themselves to journalists and, according to a piece run last year in The New Yorker, they are advised to tell not even their parents about their line of work, in case they boast about it. Its main rival in Europe, the Gault Millau, takes itself as seriously, awarding points on a scale of 20 instead of a star rating. This score, too, is decided by a team of anonymous inspectors. It was criticised in 2003 after the French chef Bernard Loiseau committed suicide following the downgrading of his restaurant's score, although Gault Millau defended itself saying the chef had been relishing the challenge of rising again. The Miele Guide is a relatively new publication, launched in 2008 as a serious attempt to evaluate the best of Asia's restaurant scene.

The annual San Pellegrino list of the world's best restaurants is another that's monitored anxiously by chefs and cooed over by the media. Produced by the British magazine Restaurant, the poll is based on the votes of more than 800 professionals worldwide within the industry (including big names such as Michel Roux Jr, Heston Blumenthal and Alan Yau), with the globe divided up into sections. This year's list, however, controversially listed only nine restaurants outside Europe and America.

The Good Food Guide in Britain remains anonymous and is still written from scratch every year; as is the AA's rosette scheme although it had to defend itself last year against accusations of bias. Past employees of the company accused it of becoming increasingly commercial, with consultancy services being offered for restaurants and hotels hoping to improve their AA ratings. And then there are the more democratic options - Zagat guides pre-eminent among them as the distillation of millions of reviews collected now from more than 70 cities across the globe. Plus the eruption of food bloggers and peer-to-peer food critics online, posting their reviews online having taken snapshots of their food with mobile phones. Of this, it's probably fair to say Egon Ronay would disapprove.