When two newlywed British doctors started their careers in Africa, little did they realise their work to find out what was killing hundreds of young children would lead to millions of lives being saved.

Prof Sir Brian Greenwood and his wife Alice, a paediatrician, witnessed a large number of infant deaths and this set him on a path towards the creation of the world’s first malaria vaccine, and the first approved vaccine against a human parasitic disease.

After four decades of work dedicated to the fight against malaria, last year the world’s first vaccine against the disease was developed and given to millions of children.

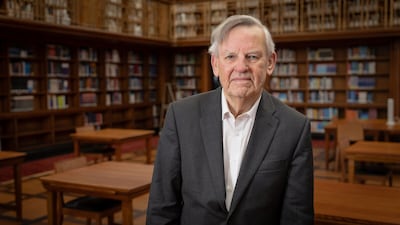

Sir Brian, who is now 85 and a research and teaching professor at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, found that the main reason children in Africa were dying was the mosquito-borne disease.

His interest in malaria was first sparked when he went to Nigeria in 1965 after graduating in medicine in the UK, and worked as a registrar at University College Hospital, Ibadan.

While carrying out research for his thesis he discovered that there were very low incidences of autoimmune diseases among Nigerians, and he wondered if this could be linked to their repeated exposure to malaria.

He returned to the UK to continue training in immunology and was given the chance to help start a new medical school at Ahmadu Bello University in Zaria, in northern Nigeria, in 1970.

'Our initial lab was in the kitchen'

Not long afterwards the couple witnessed something they had not encountered before as hundreds of people were affected over a short period of time.

“One day we had one or two cases, the next day five cases of meningococcal, going up to 50 cases a day in a small hospital. We did a census to see what was actually killing the children,” he said. “At that time the mortality was about 300 in every 1,000, three in 10 children were dying.

“We had to find out what was going on and because there was no death certification, we thought of using postmortem questionnaires [with relatives of the dead].

“It was quite emotional. They were telling you what had happened, what the symptoms were, so we were able to build up a picture.

“There were two things they were dying of: pneumonia from chest infections and malaria.”

It was there that he set up the lab, initially in a kitchen, to begin researching malaria.

“It was tough as the [civil] war was just over, it was completely different from the big teaching hospitals,” Sir Brian said.

“We didn’t have many resources. Our initial lab was in the kitchen but we did get an immunology lab eventually.

“We were seeing what the immune system would do and we showed that actually if you had malaria your vaccines don’t work so well, because malaria was suppressing the immune response.

“My wife began administering drugs to young children to help prevent malaria, to see if it would make a difference.”

Two key breakthroughs

After 15 years the couple moved to Gambia, where he took up the post of director of the UK Medical Research Council Laboratories.

There he established a research programme focused on some of the most important infectious diseases prevalent in the region at that time, including malaria.

It was here that Sir Brian, who was knighted for his work in 2012, made two major breakthroughs in malaria protection.

He and his colleagues demonstrated the effectiveness of insecticide-treated nets in reducing child deaths and showed how net distribution could be incorporated successfully into a national malaria control programme.

“I set up two new field stations in the rural areas where we could start looking at malaria,” he said.

“I suddenly noticed that everybody in this rural village seemed to have a mosquito net, and that was not the case in the villages in Nigeria.

“We thought, 'Do people use the net to stop getting bitten, would it stop you getting malaria?'

“It was not a new idea as it had been used in colonial times, but then we looked at the literature to see if anybody had ever actually proven that that was the case, that having a bed net does protect you from malaria.

“And it does, so we started doing a study to show it did.

“Then people found a way to incorporate the insecticides into the nets and it was eventually picked up by the World Health Organisation.”

Malaria vaccine – in pictures

Another breakthrough followed when his team were able to show that mortality rates in young children from malaria could be reduced by giving them preventive drugs just a few months before the mosquito season.

“We had the idea that if expat children are protected then why don’t we do that for African children as well,” Sir Brian said.

“It seemed crazy if they were dying from malaria why we were not doing that.

“There was a lot of resistance in the 1980s because people were worried about resistance coming and they thought malaria prevention should only be for tourists and expats.

“My wife had been using drugs to help children not get malaria because she knew my children never had malaria, because they took their tablets.

“We started doing studies with malaria prevention in young children following on from what we had done in Nigeria and we showed that it really did work.”

Vaccine successes

Their work has paved the way for the preventions we see today.

In 1996, Sir Brian returned to the UK to take up an appointment at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, where he continued his research on meningitis, malaria and pneumonia in West Africa.

He continued to build on the study in Gambia and conducted more trials, giving seasonal malaria prevention in Burkina Faso, Mali and Senegal.

It was a success and the results supported the earlier study’s findings.

This led to a recommendation from the WHO for preventive medicines in countries of the Sahel and sub-Sahel, with more than 30 million children now receiving the drugs each year.

Sir Brian then worked on the design of the first GSK malaria vaccine RTS, S, which in 2021 became the world's first malaria vaccine and the first approved vaccine to battle a human parasitic disease.

The first trials' success led to a pilot programme and now it has finally been recommended by the WHO to be used as a seasonal vaccine in countries of sub-Saharan Africa with a high malaria risk.

More than two million children have been given the vaccine and deaths in the affected areas have so far been cut by 13 per cent.

His work has shown that when a seasonal vaccination was combined with chemoprevention drugs it provided a very high level of protection to children over the first five years of their lives.

The results from this study have also helped the development of the second malaria vaccine, called R21, which was introduced last year and has many similar properties to RTS, S.

Despite the breakthroughs, Sir Brian’s biggest regret is that it took too long.

In 2022 the disease caused more than 600,000 deaths, nearly all in young African children, but the new vaccines that are now rolling off the production lines can finally spare millions of lives.

“There are lessons to be learnt,” Sir Brian said. “Ten years ago when Ebola broke out in Sierra Leone I was asked to help out with a vaccine and we did that in five years.

“Malaria is much more complicated but it should not have taken 30 years.

“Looking at where the gaps were and how it could be speeded up helped create the second vaccine, R21, and it benefitted from the experience in developing the first one.

“We have waited over three decades for a vaccine to be approved and now we have two in the space of a few years.

“But it is not a silver bullet. More research is needed to create a vaccine that can offer longer protection. That is the next step now.”

'It was a team effort'

Despite his work in helping to develop the vaccines, Sir Brian's greatest achievement remains training the next generation of scientists in Africa to continue the fight against malaria.

In 2001, he received a large grant to the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to set up the Gates Malaria Partnership, which supported the training in research of 40 African PhD students and postdoctoral fellows.

Sir Brian became the director of its successor programme, the Malaria Capacity Development Consortium, in 2008.

It was funded by the Wellcome Trust and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which supported a postgraduate malaria training programme in five universities in sub-Saharan Africa.

“We have to keep up the funding. For the last eight years I have been chair of a WHO elimination commission to certify countries which have eliminated malaria and I send out teams to see if it is really true.

“Since we set this up, about 15 countries have been certified as having eliminated it.

“This year Cape Verde and Georgia are on the list. Gradually the map is shrinking but more needs to be done.”

After his achievements in the battle against malaria, Sir Brian was awarded his knighthood in the UK's honours list.

“It was a team effort,” he said. “I could have ended up in Harley Street and had a big house in the south of France but I have absolutely no regrets.”