The principle sea turtles use to ensure the survival of their species involves laying a hundred eggs at a time: some will be dug out of the sand by scavengers and others will be devoured by predators shortly after hatching. But some will make it to the sea.

It would appear that the same safety-in-numbers approach is being adopted by undersea cable companies for deep-sea cables. Repairing them is a time-consuming, difficult and expensive process even though damage to the cables is far more common than generally believed.

The overall answer to cable security is diversity, Tim Stronge at the cable monitoring company TeleGeography told The National. “More cables in geographically diverse locations.”

When four out of the 15 undersea cables in the Red Sea that carry data between Asia, the Gulf and Europe were severed recently, some observers saw it as a new phase of the attacks by the Houthi rebels in Yemen on shipping passing through the Bab Al Mandeb.

It seems this was only partially true, as the US government found that the anchor from the Rubymar, the ship the Houthis had critically damaged, had dragged along the seabed and cut the cables in question.

“We currently assess that the damage sustained to the undersea cables … is a result of the Houthis' February 18 missile attack against the Rubymar, which has now sunk,” a US official said.

But while there was relief that the Houthi rebels had not sabotaged the undersea cables, it did illustrate how worried experts are regarding the vulnerability of the network.

The Hong Kong telecoms company HGC Global Communications said the incident disrupted about 25 per cent of traffic between the Middle East, Asia and Europe, but that it had taken “necessary measures” to mitigate the effect on its clients.

This amounted to rerouting data flows around the problem and making use of the remaining 11 cables in the Red Sea.

The real World Wide Web

There are currently about 574 cables traversing the world's seas, according to TeleGeography, but new cables replace older, obsolete ones regularly.

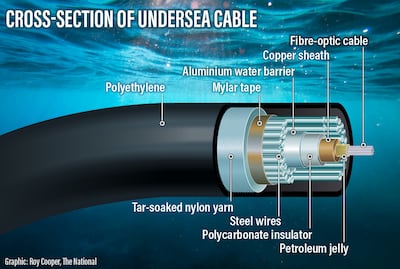

Essentially no thicker than a garden hose, these cables are made up of optical glass fibres at their core surrounded by layers of insulation and protection. The sections closer to shore are more armoured, often with steel.

At one end of the cable, data is converted into pulses of light, which are modulated to carry information in the form of digital signals. A laser then fires the pulse down the fibre optic tube, which is no wider than the width of a human hair.

At the other end of the cable, the light pulses are received and decoded.

TeleGeography estimates that as of early 2024, there were 1.4 million kilometres of cables running in the world's oceans.

Some are short, like the CeltixConnect cable from Holyhead in Wales to Dublin in Ireland. Others cover vast distances, such as the Asia-America cable which runs 20,000km from Singapore to Morro Bay in California, via China, the Philippines, Guam and Hawaii.

A lengthy history

In 1843, the investor Samuel Morse had a profound glimpse of the future when he predicted that “a telegraphic communication on the electromagnetic plan may with certainty be established across the Atlantic Ocean. Startling as this may now seem, I am confident the time will come when this project will be realised”.

After three attempts, the first transatlantic cable was laid between Newfoundland in Canada and the West of Ireland in 1858.

Even though it failed after just a few weeks, the financial benefit was apparent, almost immediately. The cable was able to transmit a message from the British government in London to its military commanders in Canada reversing an order to send a particular regiment back to the UK. That message saved the government £50,000.

Almost a century later, in 1956, the first transatlantic telephone cable, TAT-1, was laid between Scotland and Canada, carrying 36 channels. In its first day of operation, 588 phone calls were made between the UK and the US.

In the early days of the first transatlantic cable, messages would be transmitted at a rate of two or three words an hour. The new 6,600km Marea cable from Bilbao in Spain to Virginia Beach in the US can send more than 200 terabits of information per second.

“21st-century economies would not exist as we know them without fibre-optic networks,” Mr Stronge from TeleGeography told The National.

“Ordinary people may first think of the internet as TikTok videos and Facebook posts, and think they could do without them for a few days. No doubt they could, but these cables carry much more than that.

“Intra-corporate networks run on these cables, so their sudden absence would mean severe supply chain disruption. The world’s financial networks, including government central bank transfers, rely heavily on these cables as well.”

It's no coincidence that the map of the cable network looks very similar to a map of the global trade routes. That also means, like global trade, the cables run through various bottlenecks or choke points, the Red Sea is such an example.

It's at these points, argues Nick Loxton intelligence delivery and innovation manager at Geollect, that the cables can come under threat.

“Choke points like the Red Sea equal a greater concentration of traffic in a narrow, shallow strait, which in turn equals a higher probability of accidental damage, he told The National.

“Added to this, the relatively unstable location of many of these choke points makes the targeting of subsea cables and pipelines a more alluring high impact/low-cost asymmetric operation.”

The cable network carries at least 97 per cent of internet traffic worldwide, with more than $10 trillion worth of financial deals flowing through them daily.

Most of the network is owned and run by private companies and the likes of Google, Meta, Microsoft and Amazon are significant investors. It's calculated that over the next few years, large internet firms will invest a further $3.9 billion in the cable system, representing about 35 per cent of the total.

Soft underbelly

But the vast undersea cable network is often described as the “soft underbelly” of the global economy, vulnerable to both natural phenomena, maritime accidents and geopolitical tensions.

A recent report from the UK think tank the Policy Exchange said with growing geopolitical tensions, the undersea cable network was a “critical asset and a valuable target”.

Experts have claimed that Russia is currently deploying submarines around the coast of Ireland to test Nato's defences and that these craft could have the capability to sever undersea cables.

“They are too vast to defend (covering millions of kilometres) and attacks are difficult to attribute,” Sean Monaghan, UK Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington said.

“For example, fishing vessels regularly damage cables. 70 per cent of worldwide cable faults are caused by fishing equipment or ship anchors.”

Dr Bruce Jones, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said undersea cables can be damaged and sabotaged in several different ways.

“In the Baltic Sea, we saw a ship dragging its anchor – we don’t for sure know whether by design or accident – was sufficient to rupture an important cable, he told The National.

“Shark bites, believe it or not, have damaged them.

“But a major attack – severing several cables at once to create major disruption – would be handled by special purposes submarines, in which Russia has cutting edge capabilities.”

Built-in redundancy

Despite the vulnerability of the undersea cables to deliberate attacks, the greatest threat the network faces is from accidents caused by human activity, mostly involving fishing vessels.

Damage due to natural disasters like earthquakes is rare but can be costly. For example, the eruption of an undersea volcano near the Pacific island of Tonga two years ago led to its undersea cable being severed, leaving the island's 110,000 inhabitants cut off from the outside world for a month.

“Cables break all the time,” Mr Stronge said.

“The large majority of faults are caused by accident – fishing nets dragging the seabed and ship anchors pulling on cables.

“The good news is that this problem is nothing new. The undersea cable industry has responded by building a lot of redundancy into the system – if one cable goes down, many more stand by to back it up, and there are dozens of vessels stationed around the world capable of cable repair.”

Building redundancy into a network is a numbers game. But laying new cables can take more than a year to complete and the costs can run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Likewise, it's almost impossible to upgrade a cable's security once it's been laid. Most have extra and armoured coverings once they rise off the deep ocean floor to the continental shelves and coastlines but, as Dr Jones points out, pulling them up to retrofit them would be “extraordinarily costly, as would replacing them”.

“Also, the mechanics of laying cable at depth across the vast seas requires the flexibility that comes with plastics and thin coil,” he said.

While much of the undersea cable network is in private hands, it largely falls to state governments to protect them, in the same way that securing land-based infrastructure, such as electricity grids, tends to be a government responsibility.

In December last year, British, Finnish and Estonian militaries practised subsea infrastructure protection in the Baltic Sea, following an incident in early October that saw a gas pipeline and three telecoms cables damaged by a container ship dragging its anchor along the seabed.

“The damage to the cable in the Baltic Sea in October 2023 was a useful wake-up call,” Dr Jones said.

“A 10-nation coalition has been put together to do critical infrastructure protection in the Baltic Sea, but that’s the tip of the iceberg.”

Backfire

While many pundits are urging governments to increase the protection of this soft underbelly of the world economy, others say that the very global nature of the network is protection itself.

The theory is that hostile actors with the motivation and capability to sever cables would simply be carrying out an act of self-harm given that such action, more likely than not, would disrupt their communications and access to the global economy.

But relying on this 'shooting themselves in the foot' deterrent may not always be a completely safe policy, Mr Loxton said.

“It’s important not to judge any actor’s strategic and tactical logic by our own standards,” he said.

“Their decision-making process might vary significantly for our own. While any action that might appear to do more harm than good to the perpetrator would seem irrational, if the perpetrator felt that they had caused any damage or impact to their intended target, they might view that as worth the price to pay.”

Mr Monaghan believes while the interconnectedness of the world's economy affords some protection to cable networks, it depends on the players involved.

“China is more intertwined in the global economy and less likely to target services that would also harm its own growth, but it can’t be ruled out and becomes more likely as confrontation intensifies,” he said.

“Russia has not been deterred from doing so. By shutting itself off from the global economy and internet, it is experimenting with a ‘de-globalised’ strategy – although so far it is not exactly thriving.”