Family businesses are the backbone of the private sector in Arabian Gulf countries, as they continue to offer many advantages over conventional firms.

However, the most commonly cited downside of family ownership is nepotism - favouring kinsfolk in hiring, especially in important positions, for reasons unrelated to the performance of the company. Do Gulf businesses truly appreciate all of the costs of nepotism, however?

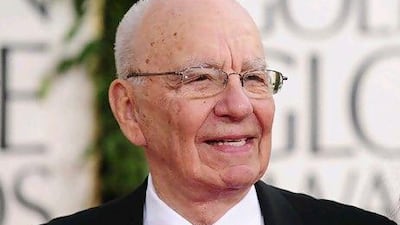

Before examining what can go wrong, it is worth reminding ourselves of the reasons why family businesses such as the Waltons and the Murdochs can outperform their conventional competitors.

First, they tend to have a more long-term outlook, because family ties create a much stronger relationship between present and future ownership generations in family businesses than in regular, joint-stock companies.

Second, family bonds also help to generate trust between the key personnel, which can be especially important in environments where contract enforcement is weak.

Third, genetic homogeneity and shared upbringing can help forge a common outlook, which can facilitate internal conflict resolution.

Rupert Murdoch, the chairman of the media juggernaut Newscorp, has appointed family members to important positions in the company. For decades, the Rothschilds reserved critical posts in their banking empire for their kin. How can such actions undermine organisational performance?

To most observers, the most salient downside relates to the quality of decision-making. By definition, nepotism implies hiring someone with inferior abilities and qualifications to other applicants on account of their having a blood relationship to management. Therefore, in principle, the company will suffer from lower quality management, especially in times of aggressive expansion or serious threats, where the value of managerial acumen is at its highest.

The poor decision-making can be exacerbated by the nepotistically-appointed family member suffering from a sense of entitlement that clouds judgement, as well as feelings of resentment from others in the organisation.

Several professional sports teams offer recent examples. Famous and highly successful players often enter management roles after retirement. It is not uncommon to see the offspring of successful professional athletes become professional athletes themselves, but in some recent cases in both football and basketball, the children have been selected for their teams by their fathers who occupy management roles, often resulting in acrimony between players due to a feeling that the son does not merit his position in the team. The damage to team morale commonly causes either the son, the father, or the team’s other star players to transfer to another team, meaning periods of poor performance by the organisation.

However, the biggest cost associated with nepotism within family businesses arguably comes in the form of diminished incentives to work hard among the remaining members of the organisation.

In modern businesses, employees, especially the high ability ones, are motivated to work not just because of their present compensation, but also because of the potential for higher, future compensation in the event that they are promoted. Employees also work hard in the pursuit of positions with higher responsibility, possibly involving the management of teams, as performing well in such positions opens the door for a new, superior job elsewhere. The promise of promotions tomorrow is a strong incentive for employees to deliver higher performance today, which is critical to the business’ success.

Nepotism undermines this key channel by weakening, or in some cases eliminating, the link for non-family members working in the company between good performance today, and higher pay and greater responsibilities tomorrow. This is because these rewards end up being reserved for family members only. Once they realise this, the non-family members in the organisation will scale back their efforts to deliver good quality work, because they are implicitly being denied the conventional reward for such efforts.

Naturally, the strength of the organisational losses relates to the strength of the priority that family members receive: if management ensures that non-family members still have a good chance - albeit a smaller one than for family members - to reap the traditional rewards for good performance, then the business’ success may decline only marginally. Conversely, when it is evident to non-family members that certain positions are exclusively for family members, then disruptively high turnover and low commitment will become common in the company’s lower echelons.

The resulting decline in organisational performance can be very hard to measure, because it reflects intangible decreases in effort. In contrast, the more commonly cited disadvantage from nepotism can be more easily seen: either manifestly bad decisions by the favoured son, or even blatant financial irresponsibility, such as taking business class tickets when economy is standard, or dining in needlessly extravagant restaurants. However, family business owners must avoid the trap of ignoring what is hard to measure, and fixating upon what is easily gauged.

As the Gulf economies look to strengthen their private sectors as part of the economic visions, family businesses will likely play an even bigger role than present, at least for a transitional period. It is critical, therefore, that the leadership of such organisations understands that the biggest costs of nepotism are not bad managerial decisions, but a demotivated workforce.

We welcome economics questions from our readers via email (omar@omar.ec) or tweet (@omareconomics).