In Rotterdam, ships from around the world cruise in and out of Europe's busiest port, a bustling industrial hub that employs almost 200,000 people and produces 20 per cent of the Netherlands' climate-changing gases.

As Rotterdam tries to cut its emissions - in line with global goals to curb global warming - shipping emissions are a particular challenge, not least because many fall outside the targets set by the Paris Agreement to curb climate change. But the city's bustling port is starting to take them on.

It has introduced financial incentives for fume-belching ships and other port facilities to invest in renewable power, with the aim of slashing the port's carbon dioxide emissions from shipping and industry by 49 per cent by 2030. By 2050, emissions would fall 90 per cent, in line with national targets, according to the plan.

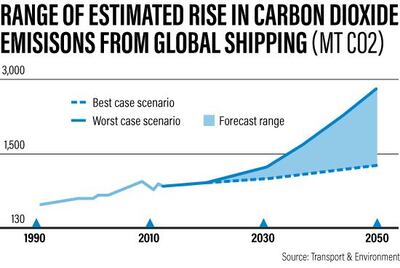

The goals fit alongside new efforts by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO) - the United Nations body that regulates shipping - to cut shipping emissions, which were not part of the Paris Agreement. The IMO in April, under pressure from low-lying island states, for the first time set a target of slashing emissions by at least 50 per cent by 2050, compared to 2008.

Such efforts will have implications beyond Rotterdam, with 90 per cent of global goods transported by ship and international shipping responsible for 2.2 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions - the same total as Germany, according to the IMO.

“Every sector needs to do its bit to contribute to the fight against climate change,” said Natasha Brown, a spokeswoman for the IMO.

Rotterdam is one of more than 25 cities, from South Korea's Seoul to Spain's Medellin, that have pledged to buy only zero-emission buses by 2025 and take other steps to make major areas of their cities zero emission zones by 2030.

Each is going about achieving the goal in its own way. But because cities account for about three-quarters of carbon dioxide emissions, according to the UN, and consume more than two thirds of the world's energy, whether they succeed or fail will have a huge impact on whether the world's climate goals are met.

In Rotterdam, greening port facilities that are heavily reliant on fossil fuels - and home to five large oil refineries - is a first big task.

“Doing nothing is not an option,” said Caroline Kroes, programme lead of the energy transition strategy at the port. But making port facilities greener must be combined with efforts to cut global shipping emissions, she said.

“The Paris Agreement is not possible if anyone stays behind. Everyone will have to move and change,” Ms Kroes said at her office in Rotterdam.

In a bid to encourage cleaner shipping, the port has introduced financial incentives for low or zero-carbon vessels, including an Environmental Ship Index, which began measuring the emissions of individual ships last year.

Since July 2017, all ships that dock at Rotterdam port have received a score out of 100 based on how much nitrogen oxide and sulphur oxide they emit - and carbon dioxide was added to the mix this year. Using the index, the port offers discounts on port costs to the cleanest ships.

Making ships and port processes more efficient also is key to slashing emissions, Ms Kroes said.

“Improving efficiency means you need less fuel, so you save costs and reduce emissions at the same time,” she said.

One way that is happening is by better coordinating ship arrivals and departures, to cut waiting time. This year the port launched Pronto, a digital platform where shipping companies and service providers can exchange information about their port visits. That information exchange alone is expected to reduce waiting times for ships and cut emissions by up to 20 per cent, according to Leon Willems, a port spokesman.

______________

Read more:

U-turning supertankers may soon be a thing of the past

Sulphur crackdown will leave dirty fuel nowhere to hide

______________

If ships on average spent 12 hours less in harbour, climate-changing emissions from their visits would fall by 35 per cent, according to a study released this month by the Port of Rotterdam Authority.

Fully electric sea ships are not yet on the horizon in the Netherlands, as they are still costly to make and infrastructure to service them on shore is not yet in place, Ms Kroes said.

But vessels that operate on rivers and other inland water bodies in the Netherlands are moving in that direction.

This year the port of Rotterdam formed a partnership with Skoon Energy, a Dutch start-up that helps existing ships switch from fossil fuel engines to electric propulsion.

The start-up builds rechargeable battery packs, known as Skoonboxes, that can be fitted on combined diesel-electric vessels. The port is helping the company establish a network of charging hubs for the swappable batteries.

More and more companies are investing in hybrid-fuel ships, with both electric engines and diesel generators, in order to cut their costs and their emissions, said Skoon Energy founder Peter Paul van Voorst.

“We see people switching [to hybrid vessels] for various reasons: efficiency, reliable quality of the fuel and sustainability. It is a no-brainer to have a clean ship. It's a better business case,” Mr van Voorst said.

Among those making the switch is Dutch company Damen Shipyards Group, which is trying out the Skoonboxes over the next few months aboard the 110-metre diesel-electric MS Borelli, a vessel that transports containers between the ports of Rotterdam and Hengelo, a city in the eastern Netherlands.

“The Skoonbox, accompanied with a network of charging hubs, will allow for full electric sailing. It is one of many ways to shift the shipping industry towards clean solutions,” said Solco Reijnders, programme manager for innovation at Damen Shipyards.

He said he "would not be surprised that in 10 to 15 years [much of] the shipping industry has shifted to completely emissions-free operations”.

Reaching the IMO's targets to cut shipping emissions will be costly and take investment from both governments and private, experts said.

“Building onshore infrastructure is definitely the government’s responsibility. Ports are not going to build this, as it is incredibly expensive,” said Johan de Jong, international relations manager at the Maritime Research Institute Netherlands.

A bit of help may be on the way. In 2018, the Dutch government allocated €1.25 million (Dh5.23m) for innovative shipping projects, and in 2019 it is expected to unveil a new Green Deal to promote sustainable shipping.

But more economically viable solutions are needed to encourage ship owners and operators to adopt low- or zero-carbon practices, Mr van Voorst said.

“It is up to the renewable energy side to become a cheaper alternative,” he said.

“That is what it eventually comes down to: is it cheaper to go clean or go dirty?”