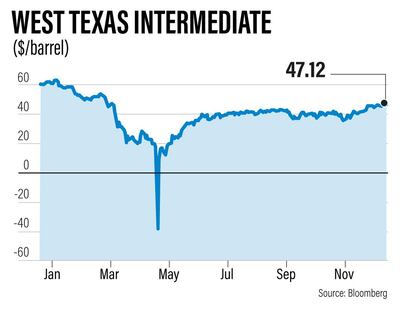

Oil prices are rounding off 2020, a turbulent year in which US crude futures fell below zero for the first time, with some amount of optimism.

International oil benchmark Brent is above $50 a barrel for the first time since March while West Texas Intermediate is above $47 a barrel.

Still, both gauges are down by about 22 per cent from their 2019 levels.

Oil prices, now at a six-month high, are poised to remain buoyant as countries begin to distribute Covid-19 vaccines.

However, optimism for a quick recovery in the sector is tempered by a focus on incorporating green energy sources.

But the industry has been reshaped as countries around the world recalibrate their energy mix to incorporate green energy sources.

The twin forces of the pandemic and a rebalanced energy mix will continue to affect the course of the industry next year.

The pandemic “created the largest oil and gas demand shock in history, but its repercussions are likely to extend through a future supply shock as oil and gas companies curtail their spending on upstream operations”, the International Energy Forum said in a report last week.

Globally, oil and gas companies have slashed their capital expenditure programmes by 34 per cent this year, which is higher than the estimated reduction in spending of 28 per cent, which began after the price slump in 2014.

Big oil companies such as BP and Shell have trimmed the size of their hydrocarbon assets, writing off $17.5 billion and $22bn as prices crashed to historic lows and demand slumped amid global lockdowns.

Spending is expected to remain tight with a “further 20 per cent decline” next year, according to the IEF.

As companies and governments tighten their purse strings next year, the outlook for oil supply remains tight, exerting upward pressure on prices.

Goldman Sachs global head of commodities Jeff Currie predicts that commodities such as oil are set to enter a “long-lasting bull market”.

“Every single commodity market, with the exception of wheat, is in a deficit today,” he said at a finance forum last week.

Still, Goldman remains bullish on prices, expecting Brent to average $65 a barrel next year. It has predicted a rapid recovery in global oil demand to 102.5 million barrels per day and expects demand to rebound to higher levels than before the pandemic.

Opec estimates that oil demand for 2020 declined by 9.77 million bpd to 89.99 million bpd, which is significantly short of the 100 million bpd average before the pandemic.

The group forecasts a smaller increase in demand by 5.9 million bpd in 2021, with overall demand expected to average 96.89 million bpd.

Opec, along with key producers outside the group led by Russia, has been instrumental in propping up oil markets in 2020, through collective action.

The group forged a historic production cut agreement of 9.7 million bpd earlier this year and is now cutting back 7.2 million bpd until the first quarter of 2021.

The alliance will meet monthly to monitor compliance and has come down hard on members such as Iraq, Opec’s second-biggest producer, and Nigeria and Angola, who have flouted the restrictions.

“Although Opec+ grabs much attention as a group when it comes to production, it produces less than 50 per cent of crude,” Barclays said in its outlook for markets.

The emergence of the US as the largest overall producer of crude will continue to pose a challenge, according to the bank.

Barclays expects prices to remain “range-bound” thanks to supply cuts, with Brent averaging $55 a barrel next year, and rising to $60 by the end of the year based on a solid recovery.

The US energy industry has been hit hard by the collapse in demand triggered by the pandemic.

WTI, the key US benchmark, briefly fell to minus $40 a barrel in April, a month described by the International Energy Agency as "Black April".

The WTI’s tumble into negative territory came close to the expiry of the benchmark’s May contract, as supply exceeded available storage capacity.

The industry remains affected, with US refinery runs below their five-year averages due to reduced demand amid the pandemic.

US production, which rose to 12 million bpd at the beginning of the year, is now about 11 million bpd. The industry is not expected to recover to historically high output levels anytime soon.

However, with WTI trending at $47 a barrel and the US having begun vaccinations on Monday, an economic recovery may prompt rival shale independents to pick up their pace.

The US shale industry and Opec+ will need to factor in the policies of president-elect Joe Biden, who is expected to overturn Washington’s “maximum pressure” strategy to contain Iranian exports and may remove sanctions on Venezuela.

Tehran is also preparing to bring its barrels to market, with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani signalling a return of supplies within "three months".

That will invariably change market dynamics and present a delicate balancing act for Opec+ as it continues to focus on running a tight ship.